Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

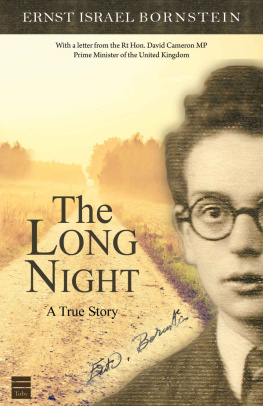

FOR ISRAEL AND SAMUEL BORNSTEIN

MICHAEL BORNSTEIN

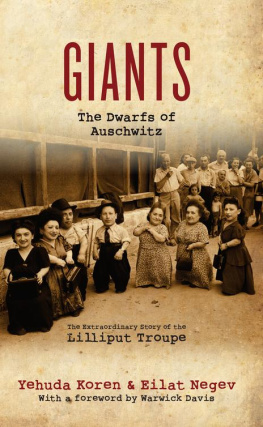

Thats me in the photothe little kid in front on the right. As a four-year-old boy, I managed to evade death in a murder mill where more than one million Jews were killed during the Holocaust. I was one of the youngest prisoners to exit the Auschwitz death camp alive.

This picture is taken from movies made by the Soviet army after they liberated Auschwitz on January 27, 1945. Nowadays, you can easily find snippets from these films online. In the image, I am with a group of children and we are showing the cameraman the inmate numbers tattooed on our arms when we arrived at the camp. Of the 2,819 inmates freed by the Russians, only 52 were under the age of eight.

For a very long time, I didnt talk about what happened to me during the war. People assumed I kept silent because it was too traumatic to discuss. Its trueI dont like to think about such awful things. When people notice my tattoo, B-1148, I mention Auschwitzbut I never dwell on that place.

Theres another reason, though. Ive always known that I had a story to tell, but for the longest time I was scared to talk, because whatever I say becomes a part of the written record of World War II and I dont want to get anything wrong. My memories from that period come in and out like a cascade of images, some clear, some fuzzy. There are times Ill catch a glimpse of a distant, tragic episodeand then the image fades away.

People have told me, Its better you dont remember. But how would you like it if you couldnt recall what your own brother looked like? For most of my life, I couldnt even answer the most basic question: How did I survive for six months at a camp known for killing children on arrival? How did I miss the Death March that cleared the camp of sixty thousand prisoners just a few days before Soviet troops arrived?

I finally know.

Not too long ago, I traveled to Israel to visit the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Museum, where a document is stored with my very name on it. This was a document written and saved by Soviet soldiers. The day I learned what my own records showed, I knew my survival proves that miracles happen in the smallest and most unlikely of ways.

For much of my life, I didnt even know images of me at Auschwitz existed. The first time I realized I was one of the children in these Soviet films, I was stunned. It was a coincidental discovery Ill share at the end of this book. I recently found something else shocking, too. One afternoon, I went looking online for the image of myself during my liberation from Auschwitz. I did a Google search and found my picture without much difficulty. Then I clicked on the Visit page button displayed next to the image and was taken to a website dedicated to claims that the Holocaust is a liethat it never happened at all! My photo was being manipulated on a website for people who wanted to warp history. Somebody had captioned my photo with a claim that it shows Jews lied when they said that the young were killed on arrival in Auschwitz, or when they said that Auschwitz was anything worse than a labor camp.

Incredibly, scores of visitors on the site had left comments, agreeing that Auschwitz couldnt have been such a bad place. They pointed to my image and several others of child survivors to show how healthy we all looked the day we were freed. (In fact, the films were taken a couple of days after liberation. We had been bundled up in many layers of clothing against the cold, and in the movie some of us are wearing adult prison uniforms as well.)

I slammed my computer shut in disgust. I was horrified. My hands shook with anger. But now Im almost grateful for the sighting. It made me realize that if we survivors remain silentif we dont gather the resolve to share our storiesthen the only voices left to hear will be those of the liars and the bigots.

I was finally compelled to talk, only Im not a writer. Im a scientist. So I turned to the third of my four children, Debbie Bornstein Holinstat, a television news producer who had often told me that my story needed to be documented. I decided to put the pen in her hand and do whatever I could to guide her in writing my story.

Finally, with Debbies help, I am letting go of the stories my relatives and I kept tightly padlocked in our minds for more than half a century. It is time.

DEBBIE BORNSTEIN HOLINSTAT

When I was little, I never really thought much about the tattoo of numbers on my dads forearm. It was just part of his skin. It was always there. Sometimes in summer when short sleeves are a must, strangers would notice it and ask, Whered you get that?

Auschwitz. Im not from around here, hed say with a laugh. Then hed immediately turn his attention back to whatever he was doing. Good luck to anyone who tried to get more information!

When my sisters, brother, and I each respectively reached about fifth grade, we started asking our father questions, too, with only marginally better results. If we pressed him, he would maybe share one beastly, heartbreaking memory. Wed ask for more information.

I dont know, Debbie, hed say. I was really young. Im not always sure how to separate what I remember, and what I think I remember. We heard that answer a lot. Then wed visit one of his cousins, and a story would slip. Wed overhear him talking to our mom, and another story would slip. An older relative would take the microphone to give a toast at a family wedding, and yet another piece of the puzzle was added. Slowly, and in pieces, we four kids grew up learning anecdotes that were woven into the fabric of our being. Like the tattoo on my dads arm, a lot of those stories were just always thererarely mentioned but always there.

When I hit my twenties and became a TV news writer, I started to think about putting my fathers stories all down in a book. The timing still wasnt right, though. I dont know, Debmaybe someday, my father would say.

Then, suddenly, seventy years after he was freed from Auschwitz, I was stunned to hear my father say, You know something? I think we should do this. Of course that meant that I was now the person who had to bear the weight of accuracy and detail on her shoulders. Ah! What did I get myself into?

When I saw the website that used my dads photo to try to manipulate history, thoughthat gave me fuel to get the job done. For every forum telling lies about the Holocaust today, let there be a hundred more that tell the truth.

Anxious to fill in every detail my father could not, I went into journalist mode. He had been imprisoned in the Jewish ghetto in his familys hometown of arki, Poland, and then transported to Auschwitz. I spoke with those who knew my fathers relatives before and after the war. Museums and genealogy centers from Washington, D.C., to Warsaw generously helped me uncover paperwork that solved more mysteries. I listened to old tape recordings of my grandmother Sophie, and slowly all of the fractured pieces of information Id been given as I grew up fell into place.