INTRODUCTION

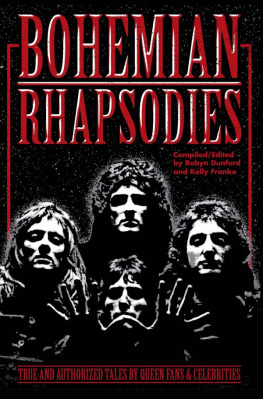

Once theyve made it, rock stars and their narratives are pretty much all the same. They fall out acrimoniously with the people who got them there in the first place; date models, travel the world, become fabulously rich and take drugs; endure at least one grubby contractual dispute; meet lots of people but are routinely lonely. And then, if they dont die, split up, or crack up, they emerge as astute businessmen writing songs yearning for the guileless, witless, much less (of everything) days of before.

Queen were typical, if not the most typical rock group ever to exist. Their only singular feature, aside from sheer longevity and an unusual degree of consistency, was that their front man became the first famous rock star to die of Aids.

There is, however, in every story of fame, a before and after. The after is the model thrown in the gigantic cake at the album launch party, and the sycophants and apologists for a life too hectic, too indulgent to even write a note home. We know this life well. Newspapers and magazines provide habitual bulletins of this extravagance and recklessness: hes sleeping with her, hes smashed up that hotel, shes snubbed so-and-so, hes sleeping with him. We know this life too well.

The before life is far more fascinating. This is where we find the desperation and dedication, the indignity and indecision. This is where, of the first UK rock generation, Brian Jones is a bus conductor poncing around jazz clubs talking wearisomely of his new group, The Rollin Stones; where, of Queens peers, Elton John plays standards for a pound a night in a London pub; where, of the current rock protagonists, Morrissey, the renowned ascetic, pesters a friend of mine two phone calls and a postcard to feature an interview with his new band, The Smiths, in a 12-page photocopied fanzine.

This is their secret life and it is the publicists first duty to erase it, or at the very least relate it selectively. The official promotional biography usually begins with the first single, everything up until this point is deemed insignificant. The atrocious early gigs and the hilarious first publicity shots are spirited away, burned, and the ashes scattered on the moors.

Queen The Early Years is an examination of those formative musical days in the lives of the four people who became Queen. Their childhood and family histories are dealt with concisely; they are entertainers, not politicians. Moreover, other peoples childhoods, like other peoples dreams, are often tedious. Instead, the book is a collection of anecdotes and thoughts of those who knew them mainly in the before life, when they were real people -unsure, apprehensive, eager, imprudent, dogged not yet the cartoons they became: Freddie the camp trouper; Roger the steadfast, soft-eyed rocker; Brian the match stick guru of the guitar; and John the stoic technician abashed by the spotlight.

It is a story which can be told relatively explicitly since it is not encumbered by vested interests. Its players have nothing to lose, unlike those that came afterwards who invested money, time, emotion and a career serving Queen. A standard biography on the group will only ever draw forth a percentage of these, and since the network around them, from the fan club to the management, is peculiarly solicitous, the unexpurgated account will either remain unwritten or suffer from the dishonour of compromise, much like the existing over-laundered official biography.

Here then are the early days of their lives, presented hopefully in the sanguine, ardent and enthusiastic fashion in which they were lived.

Mark Hodkinson, June 1995.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Paula Ridings for your encouragement, support, and love. My parents and grandmother for watching out for me. Chris Charlesworth for valued suggestions, corrections and deadline extension. Andrew King for believing in the project. Johnny Rogan, for Educating Hodkinson, and altruism all too rare in a selfish world.

And, finally, the following who shared a drink, telephone number, house space, book, video, advice, or secret: John Adams, John Baltitude, Peter Bartholomew, Neil Battersby, Peter Bawden, Ronnie Beck, Mike Bersin, Tony Brainsby, Roger Brokenshaw, Greg Brooks, Les Brown, Nigel Bullen, Clive Castledine, David Cooper, Kim Cooper, Trevor Cooper, Dave Dilloway, Michael Dudley, Chris Dummett, Tony Ellis, Rik Evans, Jeremy Gallop, Dorothy Gill-Carey, Gillian Green, Michael Grime, John Grose, Vaughan Hankins, Gill Hankins, Bob Harris, Jenny Hayes, Mike Heatley, Sean Hewitt, Geoff Higgins, Win Hitchens, Ed Howell, Rob Kerford, Fran Leslie, Sam Lind, Dave Lloyd, Paul Martin, John Matheson, Barry Mitchell, Geoff Moore, Barbara Morrison, Guy Patrick, Mark Paytress, Richard Penrose, Geoff Pester, Josephine Ranken, Phil Reed, Mark Reynolds, Bill Richards, Peter Rowan, John Sanger, Tim Staffell, Carol Stringer, John Stuart, John Taylor, William Telford, Ken Testi, Nathan Tiller, Richard Thompson, Helen Tonkin, Sarah Triptree, Joop Visser, Lawrence Webb, Rod Wheatley, Jane Wilderspin, Dave Williams, Andy Wright, Eileen Wright, Richard Young.

CHAPTER ONE

CLUCKSVILLE

Q UEEN ARE EVERYWHERE, STILL; not quite the Coca Cola Company or Ford, but not too far behind. Freddie Mercury in November 1991 and the group folded immediately afterwards, but the clich is authentic and the legend really does live on. It endures because we live in the age of the rewind. Digital remastering, video technology, CDi, CD ROM no one dies any more, bands no longer split up, the song goes on forever. We play them, pause them, hold them as our own at that moment we cherish the most. And, simultaneously, across town, where the housing estates wash up against the business parks, someone is dreaming of lunch time or home time as she packs the traditional Queen memorabilia into cardboard boxes. The records, videos, T-shirts, posters, badges, postcards, bedspreads, and sew-on patches are set for the lorries and markets. Queen and Freddie Mercury are as alive as they ever were.

We can, of course, bequeath to anyone we choose this virtual immortality. At the very least, we are each of us on a wedding video somewhere or have mumbled into a tape recorder. Thankfully, there is a natural selection of sorts. Cameras and cassettes are placed in front of all pop stars, but not to the same extent as Queen. In simple terms, they had the songs and knew how to present them, in the studio and in concert. Their songs, from the Neanderthal pomposity of We Will Rock You and Hammer To Fall to the outlandish muse of Bohemian Rhapsody and Killer Queen, were consumed voraciously by the public.

Between March 1974 and December 1992 Queen had forty-one UK Top hits (one of them, Under Pressure, with David Bowie) and amassed nearly seven years worth of Top 75 chart placings. Only one other group, Status Quo, have had more hits, and they had a six-year start on Queen. In fact, if the solo hit singles by members of Queen are added to their overall total, only three artists Cliff Richard, Elvis Presley and Elton John have had more UK hits. Queen, of course, also sold albums, more than 80 million at the last count, and rising.

They were, on the surface at least, an unlikely force to acquire such widespread adoration. Fronted by a vainglorious bisexual, their music was schizophrenic: at different times absurd, choral, linear, funky, far-out inane, rocking, mawkish or pulsating. Critics, and few had much regard for Queen save for a grudging acknowledgement of Freddies stagecraft, claimed Brian May knew just one guitar solo, while Roger Taylor and John Deacon were supposedly nothing more, and nothing less, than rock journeymen. And yet few groups, if any, have honed so many styles of music into gilded hit singles. Their very appeal lay in their sheer size, and the other world all glitzy and glamorous -stage side of the footlights. They were juggernaut rock incarnate, too bulky and brazen to embody any substantial cultural worth, but unsurpassed as entertainment value. When Freddie clenched his fist and Roger Taylor pounded the snare, Monday morning, the rain, the queue at the bus stop, the electricity bill, the smell of the office or the workshop, they were gone.