Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

In memory of the men and women who perished in the camps

Thus, with the first shout of insurrection in free Budapest, learned and shortsighted philosophies, miles of false reasonings, and deceptively beautiful doctrines were scattered like dust. And the truth, the naked truth, so long outraged, burst upon the eyes of the world.

ALBERT CAMUS, Kadar Had His Day of Fear

I was planning a novel that involved a breakout from a Chinese labor camp and had just reread The Count of Monte Cristo , looking for ideas. At Hong Kongs Central Library, I typed the word laogai , labor reform, into the computer catalog. Among the books listed, to my surprise and excitement, was the title Chongchu laogaiying , Escape from the laogai .

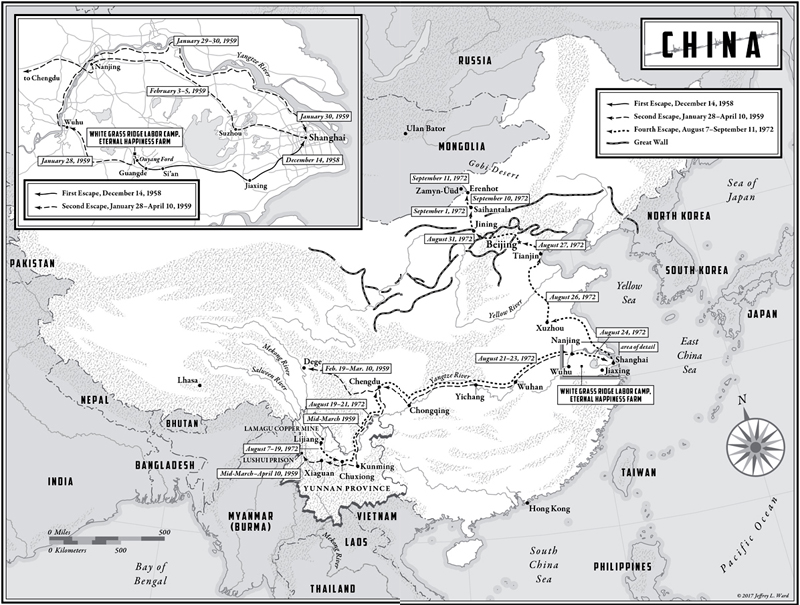

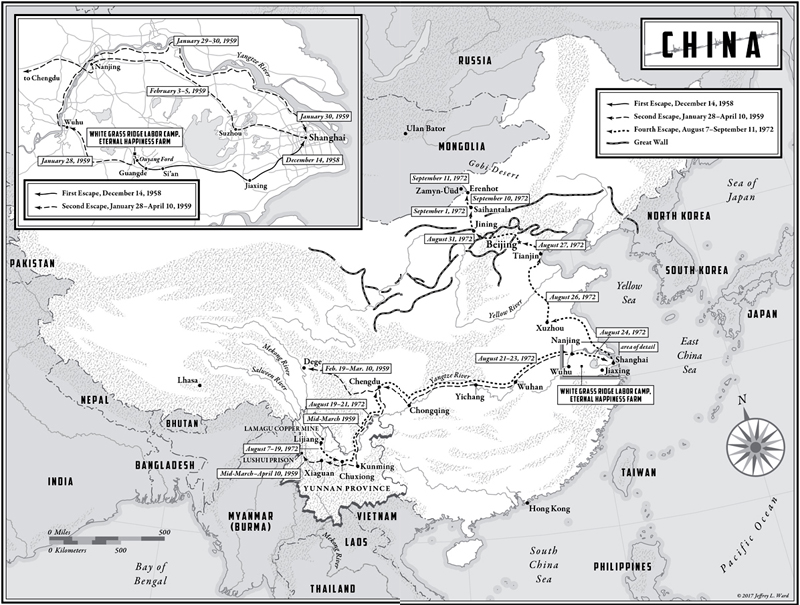

I retrieved the book from its shelf. The cover showed the silhouette of a man scaling a prison wall topped with barbed wire. The blurb read The Gulag Archipelago + Papillon : the true account of an escape from hell. It was the chronicle of Xu Hongci, one of the 550,000 men and women unjustly dispatched to the labor camps for, on Maos insistent behest, having spoken their minds in the spring of 1957. In 1972, after three failed escapes and fourteen grueling years in the camps, Xu Hongci had finally regained his freedom with a carefully planned, epic prison break.

If there is a real-life story, why write a novel? I asked myself. There and then, I decided to translate his book.

It had been published by Art & Culture, one of the many small presses in Hong Kong that cater to the millions of visitors from mainland China starving for a good, uncensored read. Paul Lee, the publisher, told me that Chongchu laogaiying , an oral account of Xu Hongcis story as told to the Shanghai journalist Hu Zhanfen, had sold eight hundred copies. He had never met the two but promised to see if he could find their contact information.

In early 2012, I called Hu Zhanfen and was saddened to learn that Xu Hongci had passed away in 2008, shortly after the publication of his book. Hu Zhanfen and I decided to meet in Shanghai, where he introduced me to Xu Hongcis Mongolian widow, Sukh Oyunbileg. Rummaging among her belongings, she brought out her husbands lifework: a 572-page autobiography, handwritten, with maps, little drawings, and many events not included in the Hong Kong edition.

Fortunately, the manuscript had been typed as a more legible Word file. The work to translate and condense it has been an eye-opening, engrossing odyssey through modern Chinese history, a journey to the heart of its darkness, always buoyed by the humane, brave voice that illuminates every page of Xu Hongcis stark testimony, written by the solitary campfire of remembrance.

Whether Xu Hongci was the only man to escape from the labor camps of Maos China is an academic question. Considering the millions who were incarcerated, probability would indicate that he was not alone. Nevertheless, when I asked Harry Wu, a highly respected historian of the Chinese labor camps and himself a laogai survivor, if he had ever heard of a successful escape, he replied, No, it was impossible. All of China was a prison in those days.

One thing is for sure: by the time of the Cultural Revolution (19661976), a failed escape spelled certain death. Gu Wenxuan was a student at Beijing University who, like Xu Hongci, fell prey to the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957. In 1966, he escaped from a labor camp in Shandong Province, made it across the border to North Korea, but was caught, extradited, and executed. Ren Daxiong, a Beijing University professor, was sentenced to life in prison for translating Khrushchevs secret speech. After staging a failed mass escape, he and twelve other convicts were made to stand before the firing squad on March 28, 1970.

In the spring of 2015, I traveled to Yunnan Province, where Xu Hongci had been arrested on the border with Burma in 1959 and subsequently spent thirteen and a half years in the labor camps. Many of the places he described have been transformed beyond recognition; the mighty, tempestuous rivers he traversed have been dammed to a standstill, and some of the dirt roads he trekked have become four-lane highways. In the picturesque town of Lijiang, the 507 Agro-machinery Factory, Xu Hongcis last prison, has been razed, while the cobblestoned streets where he was paraded now stand lined with endless tourist shops. The only discernible landmark is his beloved Jade Dragon Mountain, still towering majestically to the north.

One day, I decided to find Yang Wencan, Xu Hongcis fellow inmate from his last prison. All I knew was that Yang Wencan came from Jianchuan, a county with 170,000 inhabitants, some fifty miles southwest of Lijiang. Walking down the county seats main street, wondering where to start, I caught sight of an old man with a grizzled look, standing in the sun in front of a shop.

I am looking for a man by the name of Yang Wencan, I said.

Oh, Yang Wencan, he was Xu Hongcis friend, the man replied, as if he had surmised my purpose.

You knew Xu Hongci?! I said, taken aback.

We were together at the Dayan Farm labor camp in the early sixties. He was a tall man from Shanghai, the old man said.

We chatted for a while. I could hear that Xu Hongci was a local legend. The old man gave me complicated directions for finding Yang Wencan and began a rambling explanation of the politics and factional battles that had propelled Xu Hongci to make his final escape in 1972. Lost in reverie, he spoke in a heavy Bai dialect, and I struggled to catch his meaning. I never managed to find Yang Wencan, but that didnt really matter. A few days later, trekking along Xu Hongcis final escape route in the mountains south of Lijiang, I realized that the old mans wistful words were all I had come looking for:

He made it.

ERLING HOH

Hemfjll Skola

October 6, 2015

In 1931, Japan annexed the vast region abutting the Korean Peninsula known as Manchuriathe first step in its avowed historical mission to liberate China from Western imperialism, establish itself as the hegemon of Asia, and monopolize the continents natural resources. The following year, thirty-three days of pitched battles between Japanese and Chinese forces in the streets of Shanghai left 14,000 Chinese and 3,000 Japanese dead. In the summer of 1937, the hostilities escalated into full-scale war as Japan launched a massive invasion of the Chinese heartland. The first major battle stood in Shanghai, where the Chinese generalissimo, Chiang Kai-shek, deployed his best-trained troops to repel the aggressors. From mid-August to late November, fierce fighting raged in the city and its environs, before Chiang, having lost some 190,000 men, ordered a retreat. The Japanese army marched on the capital, Nanjing, and for the next eight years China was engulfed in one of the most lethal conflicts of World War II, with a death toll of up to 18 million people.