Copyright 2018 by Catra Corbett and Dan England

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

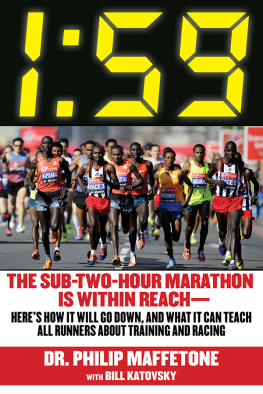

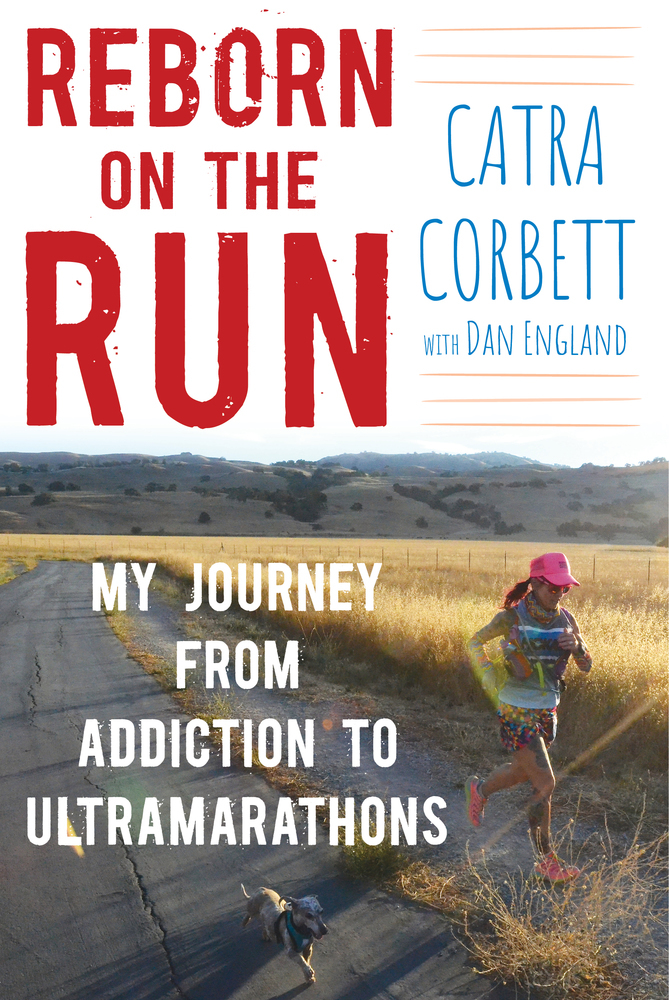

Cover design by Tom Lau

Cover photo credit: Dan England

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-2902-5

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-2903-2

Printed in the United States of America.

Table of Contents

Chapter Fourteen: Yosemite: My Second Home and a

Chance at a New Life

Chapter One

Blood, Blisters, and

a Lot of Tears

The medic looked at my feet skeptically. My boyfriend blurted out the question that no one wanted to ask.

Youre done, right? Kevin said to me.

The question pissed me off, but I couldnt blame him at the time for asking. I had just run sixty miles, ten miles longer than I had ever run in my life, and still I had forty more to go. No one, after seeing my feet, would advise me to go on. Hell, I knew that I probably shouldnt go on.

But I had to.

Kevin peered over the medics shoulder as he peeled off my socks. Both of them gasped.

The balls of my feet were smothered in puffy half-dollars, my heels were completely blistered, and my toes had been overtaken by small pockets of white, painful bubbles. One of the half-dollars had already popped, leaking clear liquid steadily down my heel. The medic began to work on popping the other blisters while Kevin shook his head in disbelief.

This was my first hundred-mile race, and it was already clear I had a lot to learn. Id made several mistakes. I was, for instance, nearly late to the race because of a last-minute dash to Walmart to buy a flashlight; it hadnt occurred to me that running a hundred miles would take all night.

And now I was suffering the consequences of my worst mistake. I was running the Rocky Raccoon 100 in Huntsville, Texas, a part of the country I knew nothing about. I lived in California, and I had no idea that the Texas humidity would make my feet swell the way a sponge expands after it soaks up water. I brought several pairs of socksI knew you had to change them during a racebut I didnt know that I needed shoes a half-size larger than usual to make room for my ballooning feet.

Californias dry air never gave me such problems. Id never even had a blister before. Now my shoes were transforming my feet into tenderized hamburger meat.

The medic scowled as he continued to work on my feet. Though initially stunned by the blisters, he was a medic in an ultrarunning race, and hed probably seen worse (at least, I hoped he had). I sighed with relief as fluid spilled out of the puffy pouches. He then started wrapping my feet in duct tape. Yes, the heavy-duty silver tape people used for household repairs, from leaky pipes to broken door handles. Until that moment I didnt know duct tape could also repair leaking blisters, but that was one of the many things I had yet to learn about being an ultrarunner. The tape secured the blisters against my skin, and when I got up to test them out, they felt pretty good for the first time in hours.

So no, Kevin, I wasnt done.

Like many people, I started running to get healthy. I switched all-night raves for early morning runs, and while I missed the rush of dancing till dawn, putting my sneakers away was not an option. I started like many do. I ran around the block, almost died, and then tried it again the next day and found I could go a little farther before I almost died again. I stumbled across ultramarathons just a few years after I became a runner. These impossibly-long races called to me. They seemed to be the answer I needed to change my life.

Four years after I started running, I competed in my first hundred-mile race. Just three months earlier I finished a fifty-miler, my second, in Napa Valley near my home in northern California, in pouring rain that left me soaked through and shivering but sure of my ability. I finished last, but many ultrarunners much more experienced than me had dropped out of that race. I kept going. So I thought that if I could finish fifty miles, in those crappy, miserable conditions, while dodging or falling waist deep into muddy puddles, then I could run a hundred.

At least thats what I thought.

I picked the Rocky Raccoon randomly from the back of an ultrarunning magazine. This was 1999, and there were only a few hundred-mile races in the whole country (as of 2017, there are seventeen hundred-milers in California alone). I had lucked into a good one for beginners. Most of the race was in Huntsville State Park, just north of Houston. Five laps through the trees and swamps got you a hundred miles.

Beginners traditionally loved the course because it wasnt over mountains or hills, or even very rocky, despite the name of the race. Most of the trail was flat and wide, stuffed with soft dirt, making for a comfortable surface. It smelled like wood and mold and the air was heavy and wet, making it feel almost like a steamy sauna. The twenty-mile loop wound through scraggly woods that blotted out the sun, muddy swamps, and lakes full of creatures Id never seen in California. A sign greeted you at the entrance: Alligators Exist in the Park. Great.

Another reason beginners loved the trail were those laps. A huge aid station in a standalone tent, the kind youd rent for a special occasion, greeted you at the end of every lap. There, runners could eat or drink, change shoes, put on or take off clothes, rub Vaseline on bloody friction rashes and, you know, have a medic put duct tape your battered, blistered feet.

As you entered, a sign warned that pukers should keep to the left. I was not a puker. At least, not yet I wasnt.

As I got up from my seat, stuffing my feet back into my too-tight shoes, the last rays of sunshine slipped behind the hills. In the thick cover of the trees, it was already dark. I would be running the rest of the race at night. I clicked my weak flashlight on and its beam danced around the trees like a pale strobe light. In a weird way, it reminded me of my old lifeall that was missing was the deep beat of dance music reverberating in my chest.

Good luck, the medic said, attempting to hide the worry in his eyes. I hope the tape holds.

Why wouldnt the tape hold? Isnt that stuff used to repair just about anything?

Well, Id find out soon enough. I started into my next lap.

Having laps is a little unusual for a long distance race. Many times, especially in an ultramarathon, youre stuck out there, alone, in the wilderness. You could get lost or thirsty or hurt, and no one would be around to help you for miles. Thats why officials check you in when you make it to an aid station. If they dont cross your name off the list, they know they eventually have to start searching for you. Sometimesespecially if you look out of itthey ask you your name or weigh you to make sure you havent lost too much weight.

Next page