CONTENTS

ABOUT THE BOOK

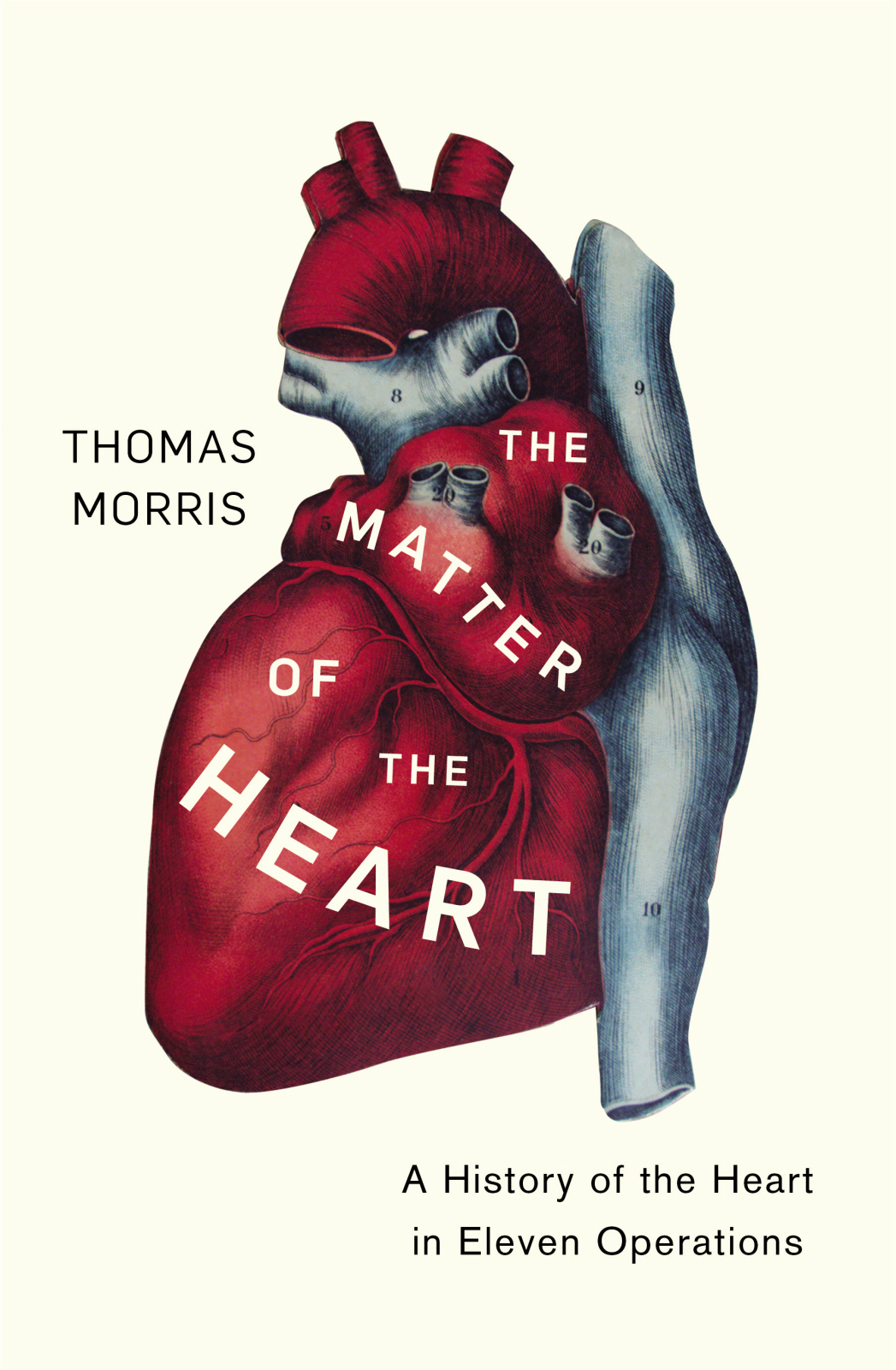

For thousands of years the human heart remained the deepest of mysteries; both home to the soul and an organ too complex to touch, let alone operate on.

Then, in the late nineteenth century, medics began going where no one had dared go before. The following decades saw the mysteries of the heart exposed, thanks to pioneering surgeons, brave patients and even sacrificial dogs.

In eleven landmark operations, Thomas Morris tells us stories of triumph, reckless bravery, swaggering arrogance, jealousy and rivalry, and incredible ingenuity: the trail-blazing blue baby procedure that transformed wheezing infants into pink, healthy children; the first human heart transplant, which made headline news around the globe. And yet the heart still feels sacred: just before the operation to fit one of the first artificial hearts, the patients wife asked the surgeon if he would still be able to love her.

The Matter of the Heart gives us a view over the surgeons shoulder, showing us the hearts inner workings and failings. It describes both a human story and a history of risk-taking that has ultimately saved millions of lives.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

THOMAS MORRIS worked for the BBC for seventeen years making programmes for Radio 4 and Radio 3. For five years he was the producer of In Our Time, and previously worked on Front Row, Open Book and The Film Programme. His freelance journalism has appeared in publications including The Times, the Lancet and the Cricketer. In 2015 he was awarded a Royal Society of Literature Jerwood Award for Non-fiction. He lives in London.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Quonset hut/Dwight Harken operation site. (Photo by Thomas Morris).

Blue baby surgery at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, February 1947. Courtesy of the Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions.

Michael Schirmer and Anna the Dog, March 1948. (Photo by Fritz Goro/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images).

on 24 March 2017.

Michael DeBakey in surgical scrubs at Methodist Hospital, operating room in background, 1978. U. S. National Library of Medicine. Reproduced with permission of the Baylor College of Medicine Archives.

A view of a cross-circulation operation performed by Lillehei, August 1954. (Photo by Al Fenn/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images).

Hypothermic heart surgery, NIH 1955. Photo by Roy Perry. U. S. National Library of Medicine.

John Gibbon with heart-lung machine. U. S. National Library of Medicine.

Philip Amundson holding an artificial mitral valve, 13 October 1960. Photo by University of Oregon Medical School. Courtesy of OHSU Historical Collections & Archives.

First Pacemaker: Senning and Elmqvists first pacemaker, 4 October 1978, Stockholm, Sweden. (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images).

Pacemaker Anniversary: Senning, Elmqvist and their first patient, Arne Larsson, holding the first pacemaker, October 1978. (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images).

First Human Heart Transplant Recipient: Christiaan Barnard and Louis Washkansky, Cape Town, South Africa, December 1967. (Photo by Rolls Press/Popperfoto/Getty Images).

Christiaan Barnard, South Africa, 1968. (Photo by Wieczorek/ullstein bild via Getty Images).

Cartoon of Christiaan Barnard as a vulture, Gerald Scarfe, 1969. Courtesy of Gerald Scarfe.

Overhead view of open heart surgery at Houston Methodist Hospital, 21 April 1966. (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images).

Haskell Karp in Surgery Recovery Room, Houston, Texas, 1969. (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images).

Barney Clark being visited by his wife Una Loy, December 1982. (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images).

Early Artificial Heart, Houston, Texas, April 1969. (Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images).

Heart specialist Andreas Grntzig holding a balloon catheter, 1981. (Photo by Ted Thai/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images).

Robotic surgery at Jewish General Hospital, Canada. (Photo by Felipe Argaez, MedPhoto, JGH).

INTRODUCTION

A few months ago I was walking through a large teaching hospital with one of the consultants, a surgeon of some eminence, when he turned to me and asked: Why do you want to write a book about heart surgeons? Were all psychopaths.

Although tempted to reply, Precisely because youre all psychopaths, I just laughed; while this affable man had an impressive ability to monopolise any conversation, I was pretty sure he was no psychopath. And after spending many hours in the company of cardiac surgeons, both in their operating theatres and in more unguarded moments, the one thing that struck me about them was how difficult they were to pigeonhole. True, Id met one or two who spoke fluently and with a startling lack of modesty about their own achievements, deftly sidestepping any questions that threatened to take us into neutral territory. But others were diffident almost to a fault, more comfortable talking about their mentors and patients than about themselves. Then there were those who were simply fascinated by the minutiae of their craft, happily explaining techniques and procedures to me at length until an exasperated secretary put a head round the door to shoo them off to a more important engagement. Most seemed to be normal and well adjusted more blessed with self-confidence than most of the population, perhaps, but also friendly and compassionate, and manifestly devoted to helping their patients get better.

So at first I dismissed the surgeon/psychopath association as a self-deprecating joke. But why had he said psychopaths? Egotists or narcissists would have been just as funny, and probably more accurate, I thought. And then I stumbled across a study in the Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England which asked simply: Are surgeons psychopaths? The most commonly identified personality traits in surgeons were stress immunity and fearlessness qualities which, the researchers noted, are beneficial or even essential when providing care in difficult situations.

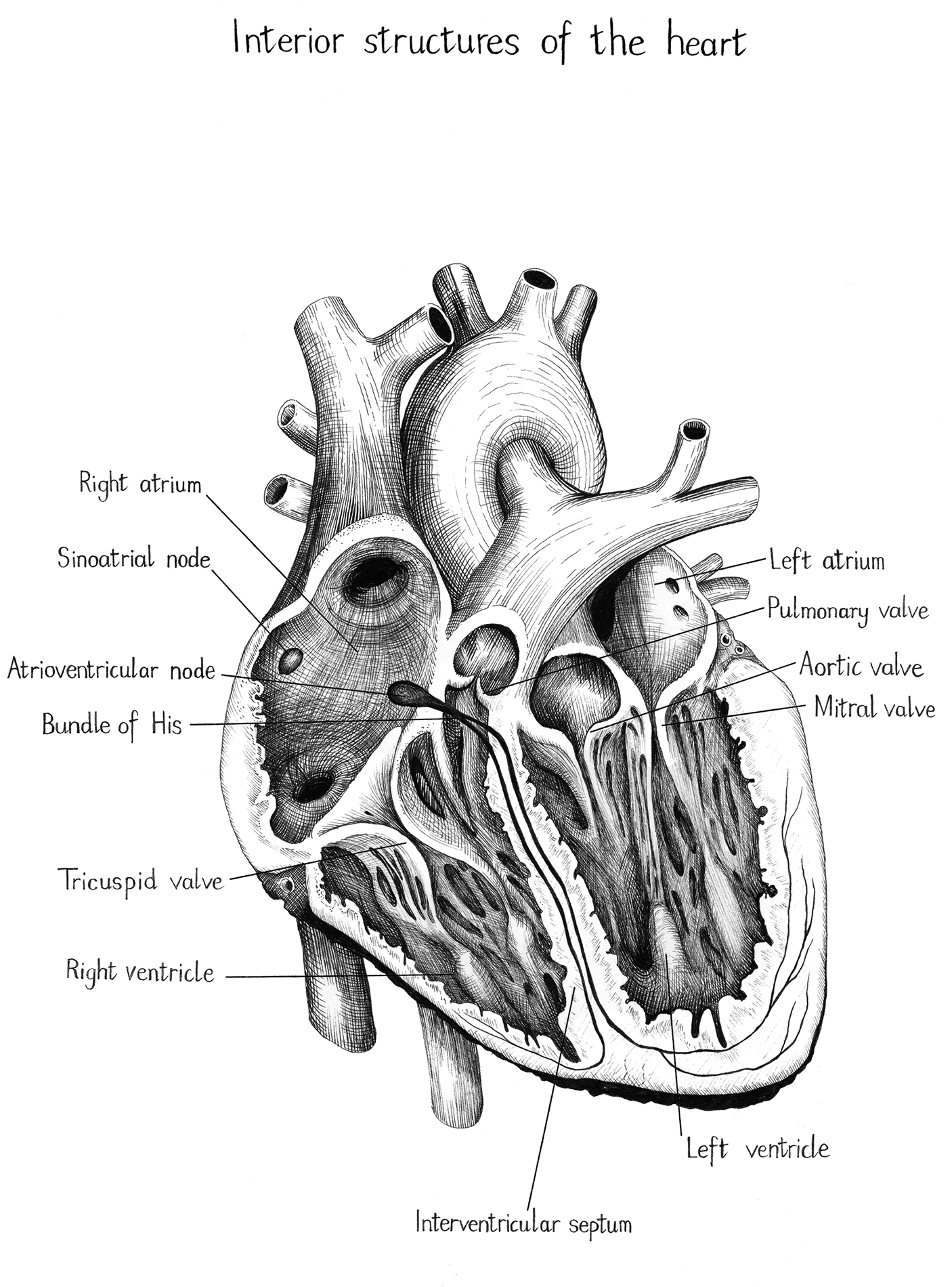

Not long afterwards I spent a day in the operating theatre of Marjan Jahangiri, a charismatic surgeon based at St Georges Hospital in Tooting. Standing next to the anaesthetist at the head of the table, I had the best possible view as Professor Jahangiri prepared to replace a diseased heart valve. The first part of the procedure had already been completed, the patients chest lay open and I could clearly see his motionless and empty heart, temporarily relieved of its work by the heart-lung machine a few feet away, which was now oxygenating his blood and circulating it through his body. Professor Jahangiri picked up a pair of scissors and in one smooth motion severed the aorta, the artery that normally carries oxygenated blood from the heart to the rest of the body. Involuntarily I took a large gulp of air: I was taken aback by the insouciance with which she had cut the heart loose from its moorings, somehow transforming it from an integral part of the human machine into a distinct and isolated viscus.