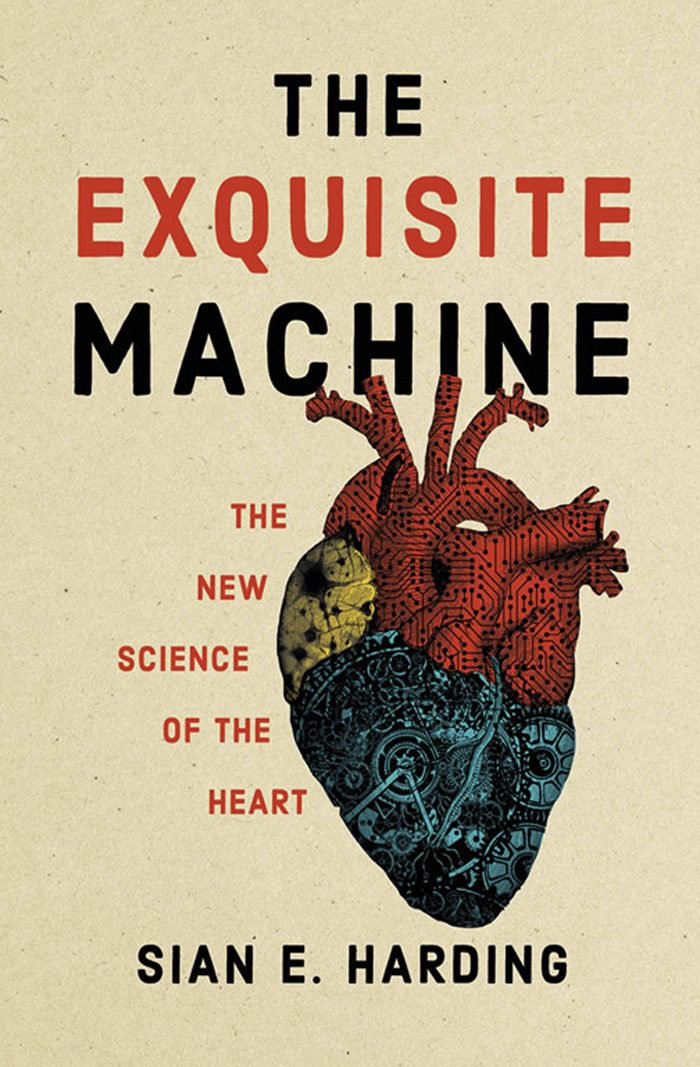

The Exquisite Machine

The Exquisite Machine

The New Science of the Heart

Sian E. Harding

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2022 Sian E. Harding

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Bembo Book MT Pro by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Harding, Sian E., author.

Title: The exquisite machine : the new science of the heart / Sian E. Harding.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2022] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021052081 | ISBN 9780262047142 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: HeartDiseasesTreatment. | HeartDiseasesPrevention.

Classification: LCC RC683.8 .H37 2022 | DDC 616.1/2dc23/eng/20211124

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021052081

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

d_r0

This book is dedicated to Ray and Elizabeth Harding

and this is the wonder

thats keeping the stars apart

i carry your heart

(i carry it in my heart)

e.e. cummings

Contents

1

Introduction

It was Valentines Day as I started to write this book, and the world was full of heartspink symbols scattered over shops and TVs, emojis strewn over our messages. The heart is our companion in grief or joy, and so has become the inspiration for poets down the centuries. To the poet, the heart is the seat of all emotions: hearts ache, explode with love, they are tender but can harden with rage, they can entwine with others and break with pain. Dominion of the heart is assured. Keats wrote, I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the Hearts affections; Emily Dickinson said, the Heart is the capital of the Mind. We feel a direct line to our emotions through this most familiar of our hidden organs, as we sense it race or pound. Yet the heart is also a marvel of construction unsurpassed by any human creation, honed by 520 million years of evolution. Now that we can observe it more directly, ticking away on the monitors that circle our wrists, we begin to understand its awe-inspiring precision. We see the heartbeats speed up or slow down with our actions and moods, counting down the seconds of our lives. To the engineer, the heart is possibly the most perfect machine ever encountered.

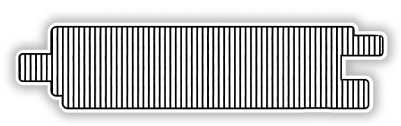

For the past 40 years I have been gazing at this exquisite construction in my laboratory. When I look at the human heart beating in the chest during an operation or lying in a dish when removed for a transplant, it just looks like a glistening lump of meat. Its hard to associate that solid red muscle with the romantic pink decoration, or the literary description of hearts soaring, bursting, sinking, and breaking. But the new tools of science are revealing a deeper beauty that lies in the perfection of the hearts construction. Once upon a time, I fell in love with a cell. It was a single heart-muscle cell, or cardiomyocyte, and I was one of the first people to work out how to take it undamaged from the dense 3D jigsaw that makes up the heart wall. It lay in the dish under my microscope with a beautiful crystalline structure, a long rectangle with parallel stripes, more like a computer chip than an organic thing. When I added calcium to the dish a long sinuous wave of contraction flowed from one end to the other. When I put electrodes across the dish and turned on the current it beat in perfect timea tiny heart, the width of a human hair.

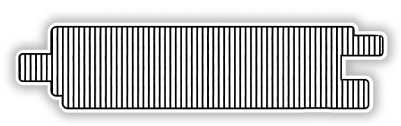

Figure 1.1

A single cardiomyocyte, one-tenth of a millimeter long.

The heartbeat may be the first thing we see of our new baby, as even by six weeks after conception this tiny flicker will be visible. During the first ultrasound scan, the doctor will point out the beating heart as a reassuring sign that all is well. We are now used to seeing incredible images in the media of the moving heart, in recordings of open-heart operations or highly detailed scans such as the MRI. The steady upward flicks, then sudden flatline, of the ECG on the heart monitor above a patients bed is a staple of medical drama. As we age, nearly half of us in the Western world will be treated with some kind of cardiac drugoften blood pressure medications or new agents to control cholesterol and lipids. We search the menus for the heart-healthy options and check our heart rate and step count on our mobile devices.

We are right to guard our one-and-only heart with tender care. As a cardiac scientist, I must explain often how dangerous and prevalent heart disease is. And that of course is true: it is the top cause of deaths globally. But I find it more astonishing how many of us dont die sooner: we can survive shocks, injuries, torture, and extreme deprivation without our heart giving up on us. The unrelenting toil of the heart is amazing, and even more so when you realize that half the cardiac muscle cells in your heart survive from the time youre born until you die. A tiny individual cardiomyocyte, barely visible, can pump away diligently for 85 years or more. Contrast this with your skin, which is shed continuously, or your liver, which can regenerate half its cells in a few weeks.

The heart shares with the brain this constancy and stability of constructionand yet both can adapt almost instantly to the challenges of everyday life. The heart can double its output in a matter of seconds or adapt to the enormous demands of supporting a growing fetus. We did not always conceive of the heart as a pump, rather, we have tended to understand its mechanism by analogy with the technology of the day. In ancient times, when smelting furnaces and cooking fires were commonplace, it was held that the purpose of the heart was to warm the blood. It was not until the seventeenth century that the English physician, William Harvey, took the imaginative leap to see the heart as a pump that drives circulation of the blood. This coincided with the increasing use of pumps in industrial processes as their workings became well known. Harvey also understood the electrical pacemaker of the heartbeat in terms of the firing of a musketa rapid trigger setting in motion a complex series of events. Now, our long history of making machines helps us to understand the incredible precision of the hearts construction with more sophisticated analogies. Our understanding of electrical circuits has combined with new tools to visualize the flow of currents across and within the heart. Our work in robotics has shown us the adaptability and versatility of the cardiac feedback systems, adjusting the blood flow on a second-by-second basis.

The heart is a construction of astounding reliability. Every day it beats 100,000 times and pumps 7,600 liters of blood. Now that about 50 percent of people being born can expect to live to 100 years old, thats more than three billion heartbeats in a lifetime. If you miss more than four minutes together, or 240 of those beats, you will die. Your washing machine spins 18,000 times in a 15-minute cycle. To match your hearts pace, that would be 10 washes per day for 1,000 years. We can send a vehicle to explore Mars, hold the worlds knowledge in a phone in our hands, and genetically modify an embryo, but we have not yet been able to build a living heart.

Next page