All illustrations are reproduced courtesy of Betty Lewis, unless otherwise indicated

TUSSY IS ME:

ELEANOR MARXS LEGACY

Sally Alexander

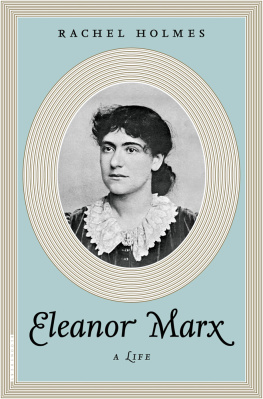

She yearned for love and freedom and wanted to be an actress, but instead devoted herself to another sort of vagabondage political agitation. An excellent linguist, she earned her living as a translator, lecturer and writer, and worked tirelessly for the cause of socialism among the late nineteenth century new lifers, anarchists, radicals and feminists of Londons socialist sects and the Second International.

Little was known of Eleanor Marxs life until the 1970s, when this book was first published, as two volumes. Yvonne Kapp, a writer and a communist, had twenty years earlier been translating the Frederick Engels/Laura and Paul Lafargue correspondence in which Eleanor kept appearing; the seeds of the biography lay in curiosity, aroused by tantalising glimpses of Eleanor as she flitted in and out of other peoples letters. Kapp was sixty-three before space, time and a small legacy from her mother afforded the opportunity of completing the work.

Eleanors life was much more than a heroic exemplar of socialist struggle and marxist principles, however. She was a woman of her time. Raised to be a lady she earned her living as a literary hack. Wanting to be an actress she succumbed to filial duty and financial need. Devilling for others in the reading room of the British Library, teaching Shakespeare and literature to private pupils, schools and classes in adult education and translating only just held at bay the spectre of governessing, that low-paid, servile employment which

From 1884 until her death fourteen years later Eleanor lived in a free union with Edward Aveling, freethinker, socialist, minor playwright and scoundrel. Aveling, according to Bernard Shaw, would have gone to the stake for Socialism or atheism, but (had) absolutely no conscience in his private life. He seduced every woman he met, and borrowed from every man.

Avelings betrayal alone might not have precipitated Eleanors death. In the last months of her life, Eleanor was also faced with Engels deathbed revelation that Freddy Demuth, the illegitimate son of Helen Demuth (the Marx familys servant and friend), was in fact not Engels child, as everyone had supposed, but Marxs. Freddy, Eleanors close friend, was Eleanors half brother. Eleanor revered her father. Family guilt and disillusion compounded her despair. In Eleanor the tensions between the wish for the artistic life and poverty, between the craving for love and the cruelty of betrayal, caused her severe mental pain which the political promise of a new world and the revision of all human relations in the future could not assuage. Ardent, clever and ultimately tragic, Kapps biography dramatises the life of a late Victorian new woman.

Eleanor was born in January 1855 in Westminster. The household parents, three small children (four including Eleanor) and Helen Demuth lived in two small rooms in Dean Street, Soho, nearly opposite the Royalty Theatre.

Several fortuitous legacies from German relatives enabled the household, with the addition of a second maid, to move into the first of several houses in Kentish Town. Kentish Town was, in the 1850s, a new suburb of London, a barbarous region carved out of clay mud and woodland, without pavements or lighting (one of the delights of this book is the descriptions of London). Eleanor followed her sisters, Jenny and Laura, to South Hampstead School, where they learned the piano, drawing, French and callisthenics, but received no preparation for an independent life, no training for a profession the reader sniffs Kapps disapproval. Indeed Marx was mortified at the suggestion. Keeping up appearances mattered at least as much to him as to his wife (whom Kapp likens to Mrs. Bennett in Pride and Prejudice). The Marxes hid their poverty from neighbours, doctors (the family were constantly ill with everything from carbuncles to smallpox), future sons-in-law, even their own daughters. It would be all the same to me if I went to the knackers yard, Marx wrote gloomily to Engels (whose unbroken generosity largely kept the family afloat) in 1866, as long as there was some money for the family.

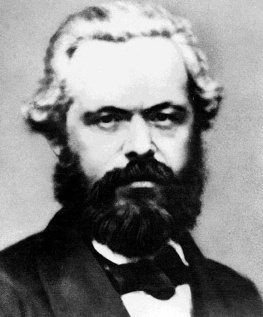

Marx himself, or his towering genius, threatens as it did in real life to take centre-stage in Eleanors biography. Marx, or Mohr, as he This is Marx at his most endearing. He could also be a tyrant.

Eleanors voice eager, warm, alive, and true as a bell

Aged seventeen, Eleanor took her first step towards independence, when in defiance of her father she became secretly engaged to Hyppolite-Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, an exiled communard sixteen years her senior. She fled to Brighton to earn her living, and completely

Eleanor grew up a revolutionary who wanted to act the two dispositions in close proximity within her. Her imaginary world hosted a whole cast of characters acquired from reading and life, whose voices amplified her own. Garibaldi was her hero. An advocate for the North in the American Civil war, she wrote to Abraham Lincoln to offer her services; her passionate identification with the Poles won her the nickname poor neglected nation; a visit to Manchester and Lizzie Burns (Engels companion and Irish nationalist) turned her into a staunch Irishman.

Theatre, like politics, was a family passion. Shakespeare was Eleanors favourite poet (as he was of the young Tom Mann who led the 1889 dockers strike

Eleanors theatrical ambitions easily quashed by a combination of unfavourable reviews, economic reality and self-doubt were soon redirected into supporting Avelings theatrical career as a playwright, actor and poet. They met early in the 1880s, and Eleanor, at least, fell instantly in love. Unable to marry because Avelings first wife would not release him, they publicly announced their union to friends, fearing wrongly ostracism. Olive Schreiner and Havelock Ellis visited them on their honeymoon. Only later did Avelings behaviour lose Eleanor several close women friends, and the trust of many others. The Avelings were enthusiasts for Ibsen, whose hatred of conventions the pillars of society insistence on individual truth and on the force of personality amounted to a revolution in the mind, which supplemented marxisms condemnation of capitalism and bourgeois society.