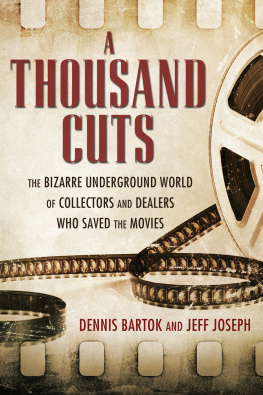

A Thousand Cuts

A Thousand Cuts

The Bizarre Underground World of Collectors and Dealers Who Saved the Movies

Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph

University Press of MississippiJackson

www.upress.state.ms.us

The University Press of Mississippi is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Copyright 2016 by University Press of Mississippi

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

First printing 2016

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bartok, Dennis, 1965 author. | Joseph, Jeff, 1953 author.

Title: A thousand cuts : the bizarre underground world of collectors and dealers who saved the movies / Dennis Bartok and Jeff Joseph.

Description: Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016005823 (print) | LCCN 2016014403 (ebook) | ISBN 9781496807731 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781496808608 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Motion picturesCollectors and collectingUnited States. | Motion picturesUnited StatesSocieties, etc.

Classification: LCC PN1995.9.C54 B37 2016 (print) | LCC PN1995.9.C54 (ebook) | DDC 791.43/75

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2016005823

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data available

Contents

Introduction

This is a book about the death of Film. Its not, of course, about the death of the Movies, which are still in very good health, thank you, both commercially and creatively. Before you jump to the conclusion that what follows is one long, sad dirge for the passing of old-fashioned analog cinema, a last call at the bar before the cowboys ride into the sunset, it isnt. If anything, its a sort of mad Irish wake for an underground subculture of often paranoid, secretive, eccentric, obsessive, and definitely mad film collectors and dealers, who made movies their own private religion.

Certainly the movies face far more competition in the twenty-first century from other forms of media: the video game industry may have caught up with motion pictures in terms of annual grosses, but it hasnt replaced the movies. If anything, theres a fascinating interchange going on between the movies, video games, and other media: my son Sandor watches the Harry Potter movies so he can better play his way through the Harry Potter video games, and then goes back and reads the Harry Potter books to enrich and fill in what he missed. This recombinant-DNA intermingling of media new and old reminds me of a unique phraseology thats recently popped up in Hollywood contracts: in any media, whether now known or hereafter devised, or in any form whether now known or hereafter devised, an unlimited number of times throughout the universe and forever. But my son, and his, will experience the movies in a completely different way than I experienced them, and as the dozens of film collectors and dealers interviewed for this book experienced them. There will still be that magical light coming out of the booth, as dealer Woody Wise remembers from his childhood at the Sylvia Theater in Franconia, Virginia, but that light will no longer be projected through a strip of film rattling through a Motiograph projector at twenty-four frames per second. And with that difference in experience, something in the relationship between audience and image, Man and the Movies, has changed forever.

A tremendous achievement for any technology. But its time has drawn to a close: its inexorably been replaced by digital formats, and theres nothing we can do about it. When George Lucas came to the American Cinematheques Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood in 2003 for the opening night of an Industrial Light & Magic and Skywalker Sound tribute Id organized there, I had a brief conversation with him in what passed for the green roomactually a cramped space outside the box officeabout the impending change from film to digital. I mentioned a nitrate dye-transfer Technicolor print of Powell & Pressburgers art-house classic The Red Shoes (1948) that the Cinematheque had recently screened. Lucas listened calmly and thoughtfully as I described how beautiful the print was, how watching it was like literally stepping into a time machine and seeing the movie the way audiences had originally seen it. Finally the creator of Star Wars nodded his head: I can do the same thing digitally, he replied. I can add scratches and noise to the soundtrack. I can make it look like nitrate, like Technicolor, or whatever you want. At that point I knew the writing was on the wall. Film was dead. Long live Digital.

The industry trade paper Hollywood Reporter, in an April 15, 2013, article titled CinemaCon: The End of Film Distribution in North America Is Almost Here, wrote, By the end of this year, distributors might no Eastman Kodak, at one time synonymous with still and motion picture film, filed for bankruptcy in 2012. These are, without a doubt, echoes of the death knell for film. Media changes. New media come in, old media become obsolete. But its not only the technology that changeslives and familiar habits are transformed too. Were living in an era when record stores and video rental stores have quickly become a thing of the past. So has film, and its taking with it the bizarre network of collectors and dealers who obsessed, fought over, hoarded, and occasionally stole these precious images.

This book, then, is not just about the inevitable decay and death of the film medium itself, but its also about the often strange, and strangely compelling, lives of film collectors and dealers, many of whom are dealing with their own issues of aging and mortality as they approach or reach retirement. More than a few collectors said they simply stopped projecting films because it was too physically exhausting to heft film cans or do changeovers; one die-hard collector, Latino graphic designer-turned-truck-driver Rik Lueras, uses his projection booth now to store his medical equipment. This book is about a postWWII generation of (mostly) white, male collectors and dealers, many (although not all, by any means) of them gay men, who pursued their love for the movies with a glorious, unreasonable passiona passion that may never quite be equaled, simply because they grew up in an era when access to movies was so limited. How many collectors were there at the height of the underground market? Its hard to say, but Donald Key, publisher of the collectors bible, The Big Reel magazine, says that subscriptions at their peak reached 4,800 in the late 1980s, which is a good guess for the number of collectors total at the time, at least in the United States.smaller size of their national film industries also meant there were generally far fewer collectors overseas. Its worth pointing out that while there is a distinction between film collectors and dealers, the lines are often blurred. Many collectors backed into dealing part-time (or eventually full-time) to fund their habit. A good rule of thumb is that while not every film collector became a dealer, almost every dealer started out as a collector.

But why film collectors in particular? Or as Gremlins director Joe Dante bluntly asked me when I came to interview him, So, whats your reason for writing this book? Part of it is that film collectors are an endangered species. They are dying along with their obsession, and there is something particularly fascinating and moving about seeing them go down with their proverbial ship. Even in the age of the Kindle and e-books, hundreds of thousands of new books are still being printed on paper. Books and book collectors will be around long into the foreseeable future. The same goes for comic book, stamp, coin, baseball card, record, and almost every other kind of collector you can think of. But film stock is enormously expensive to make and process. Even for those directors dedicated to shooting on celluloid as long as its availableand thats the key phrase, as long as its availablelike Quentin Tarantino, Christopher Nolan, Judd Apatow, and J. J. Abrams, getting access to raw film stock and the means to develop it is going to be increasingly difficult as laboratories and suppliers shut down their operations.the introduction of Eastmancolor LPP (low-fade positive print) stocks in 1982, prints generally fell into two broad camps: dye-transfer (or IB) Technicolor, which is highly resistant to fading, and Eastmancolor-derived stocks like 20th Century Foxs DeLuxe Color, Warner Bros. WarnerColor, and others, which have turned anything from bright crimson to riotous purple as theyve faded. Over the years desperate collectors have turned to all sorts of homemade fixes to restore color to faded prints. In his 1974

Next page