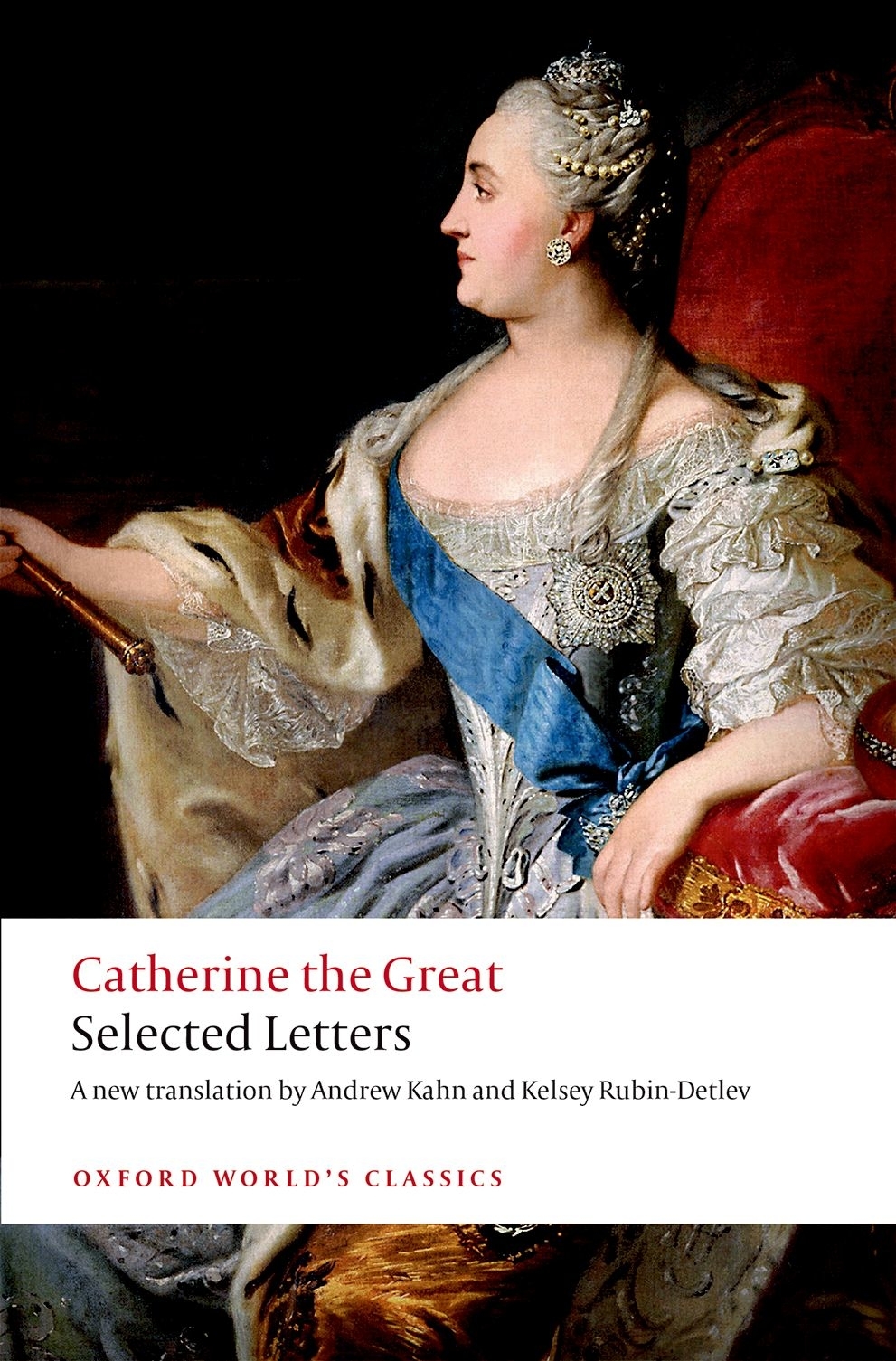

oxford worlds classics

Selected Letters

The future Catherine the Second (or Great) was born Princess Sophia Augusta Fredericka of Anhalt-Zerbst in the Prussian port city of Stettin (now Szczecin, Poland). In 1744 she took the name Catherine on her engagement to Grand Duke Peter, heir to the Russian throne. After her husband was deposed in 1762, she became the empress and reigned till her death in 1796. A reformer on the domestic scene and an ardent proponent of an expansive Russian foreign policy abroad, she was an active legislator and military commander and prided herself on her close management of a vast, multi-ethnic empire that enjoyed considerable commercial and industrial growth over the period. After putting down an extensive peasant rebellion in 17734, Catherine implemented an important set of administrative reforms but necessarily stopped short of dismantling serfdom, the basis of the Russian political economy. Even as an absolute ruler, she owed her security on the throne to her ability to balance oligarchic factions. She waged two victorious wars against the Ottomans, annexing Crimea in 1783; she made Russia a leading diplomatic presence in Europe, combating French animosity early in her reign, mediating in European conflicts, and colluding with Austria and Prussia in repeated partitions of Poland. A voracious reader of contemporary literature and philosophical writings, the empress courted the intellectual elite of Europe and used her prestige to project abroad Russias image as a civilized and culturally distinguished land, marked by values of tolerance. At its peak in the 1780s, her reign saw the adoption of free press laws, and she patronized writers of secular literature, overseeing the flourishing of the theatre and the Academy of Sciences. Active herself as a playwright, amateur historian, and philologist, Catherine was a tireless epistolary writer for the sake of recreation as well as business.

A ndrew K ahn is Professor of Russian Literature at the University of Oxford and Fellow of St Edmund Hall, Oxford. He has edited several volumes for Oxford Worlds Classics, including Pushkins The Queen of Spades and Other Stories and Montesquieus Persian Letters, and for Oxford University Press is the author of Pushkins Lyric Intelligence (2008) and co-author of A History of Russian Literature (2018).

K elsey R ubin -D etlev is Assistant Professor of Slavic Languages and Literatures at the University of Southern California. She was previously the Foote Junior Research Fellow in Russian at The Queens College, Oxford.

oxford worlds classics

For over 100 years Oxford Worlds Classics have brought readers closer to the worlds great literature. Now with over 700 titlesfrom the 4,000-year-old myths of Mesopotamia to the twentieth centurys greatest novelsthe series makes available lesser-known as well as celebrated writing.

The pocket-sized hardbacks of the early years contained introductions by Virginia Woolf, T. S. Eliot, Graham Greene, and other literary figures which enriched the experience of reading. Today the series is recognized for its fine scholarship and reliability in texts that span world literature, drama and poetry, religion, philosophy and politics. Each edition includes perceptive commentary and essential background information to meet the changing needs of readers.

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, ox2 6dp,United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries

Andrew Kahn and Kelsey Rubin-Detlev 2018

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First published as an Oxford Worlds Classics paperback 2018

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018944466

ISBN 9780198736462

ebook ISBN 9780191056130

Printed in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Contents

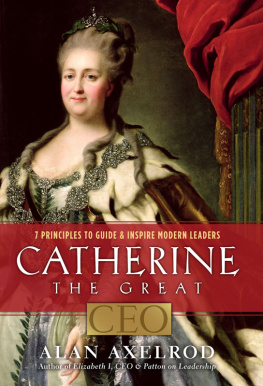

Catherine The Great has fascinated the public from her reign as Empress of Russia (176296) to the present. Her charisma, her momentous times, and the story of her life have made her the inexhaustible subject of numerous biographies, documentaries, exhibitions, plays, novels, and satirical cartoons, and she has been impersonated on stage and screen by the likes of Mae West (in a 1944 Broadway play called Catherine was Great), Marlene Dietrich, and Catherine Zeta-Jones. Catherine was active as legislator, commander-in-chief, and diplomat during tumultuous times, starting with the Seven Years War (175663) and continuing through the disastrous yet transformative years of the French Revolution. Catherine was also a woman of no mean literary ambition and activity. She lived in a great age of letter-writing and stands out as one of its most accomplished practitioners. It is impossible to understand the course of her reign, the enigmas of her personal life (sometimes depicted as luridly oversexed), and the complexities of her achievements without knowledge of her correspondence, a correspondence remarkable for its magnitude and quality of writing. Of great historical interest, it also showcases the art of the letter, reflecting the intellectual ferment of the High Enlightenment and her skill in the genre.

The daughter of a minor German prince in Prussian employ, the adolescent Princess Sophia Augusta Fredericka of Anhalt-Zerbst left for Russia in 1744 to conclude an arranged dynastic marriage with her cousin, Karl Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorf (Emperor Peter III from 1761), who, as a grandson of Peter the Great, had been named heir to the Russian throne by his aunt, Empress Elizabeth Petrovna. After her acceptance of the Orthodox faith upon her engagement, the young grand duchess became Ekaterina (Catherine) Alekseevna, the name chosen for her by Elizabeth in honour of her own mother, Empress Catherine I. Married at the age of 16, the new Catherine learned to bide her time in an unhappy marriage and navigate the hostile court environment, becoming in some ways a self-made woman. Catherines sharp intelligence helped her to manoeuvre through the pitfalls of court intrigue the subject of some of the earliest correspondence in this anthology (Letters 48)and prepared her dramatic ascent through the coup dtat that overthrew her husband, Peter III, in June 1762 (Letters 912). After consolidating her position on the throne in the 1760s, she made serious attempts at modernizing Russian institutions and governance structures, while little more than a decade into her reign she oversaw the repression of a major peasant and Cossack uprising, the Pugachev Rebellion, which threatened the entire Russian state (the subject of many vivid letters). Peter the Great had established Russias diplomatic and military presence by disabling Swedens northern empire. Fifty years later, Catherine succeeded in the south by conquering Ottoman lands, then annexing Crimea, and eventually participating in the complete removal of the state of Poland from the map of Europe. Russia in her reign became a formidable power in the world political arena. Pitted against her, or in sometimes partial alliances, were Prussia, the Austrian Empire, and France. In the 1790s, when the French Revolution threatened to undo a legacy of continental stability and enlightened absolutism, she faced this new challenge head-on, proudly reviewing her accomplishments and asserting their lasting significance for Russia and for Europe as a whole (Letters 184, 1867).