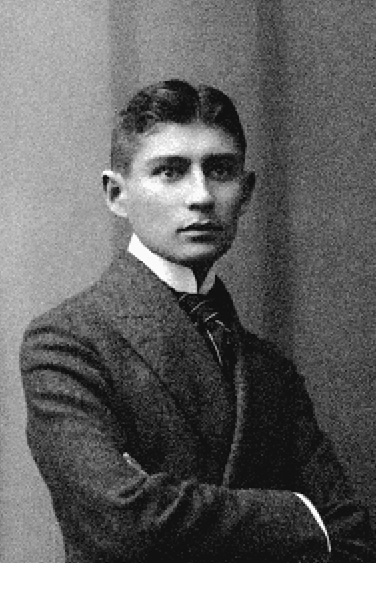

Is that Kafka?

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Preface

For some, hes a frightening figure. Others, who havent read him but have heard tell of him, are only afraid he would frighten them. And many more find him sad, though they cant quite tell you why. Some, sensing a hint of depression, delicately set his slender books aside. Yes, there are plenty of reasons to keep him at arms lengthnot least of which is the rumor that he was more or less insane, which persists to this day and finds ample nourishment even in his finished works. Of course, it is not the task of literature to provide a quick and reassuring solution to each problem that it raises, or to prove that everything has its good side; we know that that isnt true, and we dont like it when authors take us for fools. But when literature takes up the real failure that none of us can escaperefracting it again and again, with evident relish, in imagined failuresand when, in addition, it wraps all this up in an unrelenting, directionless discourse about failurethen we begin to wonder if the author has not perhaps given free rein to a thoroughly private obsession, and we ask why we should listen and look on as attentively as he apparently expects.

For some, he breeds impatience, nervousness. His texts are enigmatic, and he seems to take pleasure in leading the reader astray, along labyrinthine, inescapable loops of thought. Gregor Samsa, transformed into an insect, and Josef K., arrested for no apparent reason, are his most famous inventions. What happens to these two characters is thrilling, fantastical, and gives us food for thoughtbut defies all of our expectations. Of course, anyone who nurtures a relationship (however tenuous) to literature needs only a few pages to understand that any reasonable explanation, any solution, would destroy these fictionsno matter how badly their heroes (and their readers) might wish to resolve the tension. There is no consolation we can hold on to herethe stringencies of innovative literature forbid it. The best we can hope for is a very fleeting comfort, like that experienced by a man who, finding himself in free fall, reassures himself that so far everything is going just fine.

And yet some readersand their numbers have not dwindled over the decadeswholeheartedly embrace him, experiencing his prose as the greatest pleasure that literature has to offer. Not repelled by mysterious plots or by ultimate catastrophes, such readers accept these as images of the impenetrability and finitude of human life, and especially of life in modern, administrated, mass societies. For what makes these images so compelling are not the ideas concealed within them, always open to debate, but rather their aesthetic forms: the crystalline language, the provocative simplicity, the wealth of unheard-of, wonderful metaphors and paradoxes, the virtuosic mastery of dream logic, the showering sparks of humor that illuminate even the darkest moments of calamity. Capable of absolutely anything, he is the author who knows no carelessness, no linguistic ornament, no empty effects. He is the author who never sleeps.

It was inevitable that Franz Kafkathe author whose reputation as a meteoric figure and a future classic was already taking shape just a decade after his early deathwould generate intense biographical interest. The same all-consuming desire for human explanations that his texts continuously rekindle seemed to spill over into Kafkas private life, and finally into his entire cultural, political, and social milieu. The question was what sort of person could have produced such things and how he could have become that personand for years, this legitimate question carried with it the unspoken suspicion that such a person couldnt be normal. The first anecdotal accounts of Kafka that became public seemed to reinforce this suspicion: he had been obsessed with writing, and yet in his will he had ordered all of his manuscripts destroyeda desire for self-effacement that we (by common consent) feel was justly ignored without a second thought. Whats more, it seemed that Kafka had led a life that was to all appearances peculiarly conventional and constraineda civil servant entangled with his family, with few friends, who saw little of the world and never experienced a fulfilling sexual relationship. An ascetic who bet it all on one card, literally surrendering everything else in his life for a highly specialized artistic achievement whose fruits he would never even get to enjoy. No oneand least of all a writerwould want to trade places with a man like that.

Over three quarters of a century, this grainy picture came more and more clearly into focus, but even as the explanations grew more convincing for the ties between Kafkas work and the deeply convoluted Jewish-Catholic, German-Czech world in which he lived, the contradictions and the sheer strangeness of his psychic makeup became increasingly evident. To be sure, the secret of his unprecedented production remains largely elusive, and any effort to understand Kafka is still an essentially interminable task. Nevertheless, thanks to decades of international, interdisciplinary research, we now possess a very precise concept both of this man and of his world.

Yet this research hardly seems to have made any impression on the popular imagination, where Kafka has persisted as the quintessential archetype of the writer as a sort of alien: unworldly, neurotic, introverted, sickan uncanny man bringing forth uncanny things. This is only a clich, but a very powerful one. Because, even if these myths are largely kept alive by those furthest removed from literaturethe mass medianevertheless it has been extraordinarily difficult for even experienced readers to resist the pull of this cultural stereotype, powered as it is by such vivid images, which survive for as long as we find them attractive: a cobblestone alley damp with rain in nighttime Prague, backlit by gas lanterns... piles of papers, dusty in the candlelight... the nightmare of an enormous vermin. All of that is Kafka, no matter what literary scholarship might tell us.

Its hard to argue against images, but counter-images can help us to destabilize their monopoly somewhat. These 99 Finds from Kafkas life and work display him in unexpected contexts, in unexpected lights, and they allow us to hear rarely detected undertones and overtones. Each one, taken in and of itself, does not mean all that much: some are only a trace, and some are quite unassuming, offering merely a new perspective on a well-known subject or catching Kafkas reflection in others memories. But taken togetherand this is the chief criterion for their selectionthey quietly divorce us from the clichs, and allow us to see that it might be useful after all to try other approaches to Kafka, approaches that were always there, butplastered over with Kafkaesque images and associationslargely forgotten.

Here Kafkas sense for the comic plays a preeminent and paradigmatic role. His humor is by no means always cryptic, as one might expect from his inscrutable texts: it can be nave and slapstick, revealing his pleasure in wordplay and punch lines, in an adept juggling of motifs, perspective shifts, and inspired scenarios. If Kafkas artistic exertions were often deadly serious for him, they also always preserved a playful element from which he derived great enjoyment. Beyond the borders of literature, he carried his games into his letters and diaries, and even into the gestures and episodes of his everyday lifemostly consciously, but occasionally against his own will, and yet always with his characteristic, stubborn consistency.