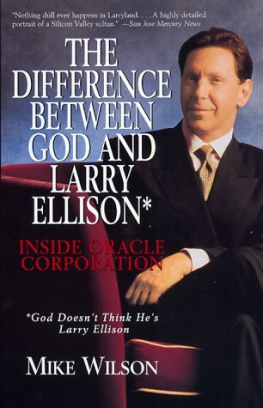

Copyright 1997 by Mike Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher. Inquiries should be addressed to Permissions Department, William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1350 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10019.

It is the policy of William Morrow and Company, Inc., and its imprints and affiliates, recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, to print the books we publish on acid-free paper, and we exert our best efforts to that end.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, Mike

The difference between God and Larry Ellison : Inside Oracle Corporation / by Mike Wilson

p. cm.

ISBN 0-688-14925-1

1. Ellison, Larry. 2. Oracle CorporationHistory. 3 Computer software industry United StatesHistory. 4. BusinesspeopleUnited S tatesBiography. I. Title.

HD9696.C62E57648 1997

338.7'610053'092dc21 97-20100 CIP

Printed in the United States of America

FIRST EDITION

2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

BOOK DESIGN BY LAURA HAMMOND HOUGH www.williammorrow.com

For the Wilsons

Carol, Dyami, Lena, and Kirby

And the Taylors

Phil, Joanne, Emily, Ben, and baby Jess

You're a reporter. You want to know what I think about Charlie Kane. Well, I suppose he had some private sort of greatness, but he kept it to himself. He never gave himself away. He never gave anything away. He just left you a tip.

He had a generous mind. I don't suppose anybody ever had so many opinions. But he never believed in any- thing except Charlie Kane, he never had a conviction ex- cept Charlie Kane in his life. I suppose he died without one. It must have been pretty unpleasant. Of course, a lot of us check out without having any special convictions about death. But we do know what we're leaving. At least we believe in something.

From Orson Welles's 1941 film Citizen Kane

One

LARRY ELLISON WALKED DOWN THE LONG HALLWAY, HIS SNEAKERS chirping quietly as he approached the living room. The hallway was narrower at his end than at mine, so Ellison seemed to grow larger as he moved toward me, an optical illusion that would have pleased him. He wore white gym shorts and a white T-shirt, and his youthful face was still glowing red from his afternoon workout.

I had arrived thirty minutes earlier, at the appointed time. Klaus, a member of Ellison's domestic staff, had ushered me inside, and Maria, the maid, had given me a soft drink.

"Hi, sorry I'm late," Ellison said, extending an outsize hand. Embroidered onto his shirt was the word SAYONARA , the name of his yacht. His mouth was saying hello, but his shirt was saying good- bye. The contradiction seemed appropriate: As the entire world of high technology knew, Larry Ellison was a hard man to pin down.

We chatted for a moment. Then sayonara he excused him- self and disappeared up the spiral stairway to take a shower.

After he had rotated out of sight, I had a few more minutes to look around. Standing in the vast living room of Ellison's San Fran- cisco home was like being transported into the pages of Architectural Digest. A couple of black lacquer stereo speakers stood like monoliths near the fireplace, a Steinway grand piano stood three-legged in the corner, and on the coffee table a pair of wire-frame glasses lay on top of a stack of art history books. The house had many other impressive features that could not be seen from the living room. A computer in the closet controlled more than five thousand lights, all of which could be dimmed or brightened according to the time of day or El-

[ 1 ]

lison's mood. In the entertainment area an eight-thousand-dollar video projector produced a razor-sharp picture even when the room was not fully darkened. (Someone had told me that NASA used the same kind of projector at Mission Control.) The house also had a courtyard patio made of bronze tiles, a unique handmade snooker table in the game room, and two shiny stainless steel garage doors that looked great except that they showed fingerprints.

Probably the most remarkable thing about the house was the view"the best view money can buy," the designer had told me. 1 I couldn't quarrel. Through the broad living-room windows I could see Alcatraz Island, Sausalito, the Golden Gate Bridgethe great, misty San Francisco panorama.

And this was just Ellison's entertainment house, his "pied-a- terre," the home where he gave parties and did business whenever he happened to be in the city. His main residence, a ten-thousand- square-foot Japanese-style house with a large garden and an au- thentic teahouse, was down the peninsula in Atherton. And he was currently building a new Japanese estate on twenty-three acres in Woodside, a wooded village in the Silicon Valley hills. The projected cost: forty million dollars.

He could afford it. Only days before this interview, my first with Ellison, Forbes magazine had estimated his net worth at six billion dollars. According to the magazine, that made Ellison the fifth-richest person in the United States. Some of the people on the Forbes 400 didn't like having their fortunes discussed publicly; as I was about to see, Ellison was not one of them. He enjoyed the attention.

Soon he reappeared, wet-headed from the shower and dressed casually in slacks and a black, short-sleeve polo shirt. He led me to a table in the far corner of the room and offered me a seat. The table had place settings for two. After a moment the staff arrived with plates of fresh greens, the first course of what turned out to be a three-course lunch. Ellison, a man of legendary appetites, drank about a quart of carrot juice with his meal.

I began by asking him to talk about his childhood in Chicago.

He did, briefly. Thenseamlessly and effortlesslyhe segued into a speech about Bill Clinton's failed attempt several years earlier to re- make the American health care system. Ellison believed that the President should have left health care alone and focused on education.

I have added punctuation to make the following paragraph readable, but when Larry Ellison was speaking, there were no com- mas or hyphens. He talked so fast that he mutilated some sentences and even some words. For example, when he said the word "gradu- ating," it sounded like gradjing. He ate "uate."

"People get on airplanes all over the world and fly to the United States to get health care. And we have an educational system that would be an embarrassment to a third world country," he said, over- stating the case, as he often did. "No one flies here to send their kids to the seventh- and eighth-grade public schools in San Francisco or New York City or Chicago. I just think Bill Clinton was wrong.... First of all, health care is not a government monopoly. Education is. So government taking responsibility for fixing this problem is abso- lutely appropriate. Government taking responsibility for fixing health care, which isn't brokenPeople get on airplanes and fly here. Don't get me wrong. I think that there are access problems with our health care system. The very poor can't get at it. Interestingly enough, one of the big groups who don't get to have health care are people just graduating" gradjing "from college.... So a lot of these statistics can be very misleading. Some of the people who don't have access really are not at risk. There are othersthe very poorwho really are at risk, and they don't have access, so we have to do something about that. But I don't think you revamp the entire health care sys- tem, which delivers incredible quality health care, the best health care in the world, you don't revamp that system of private-public cooperation that exists right now and turn it into a public monopoly."

Next page