Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Join our mailing list and get updates on new releases, deals, bonus content and other great books from Simon & Schuster. CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

CONTENTS

To Alison and the children with all my love

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

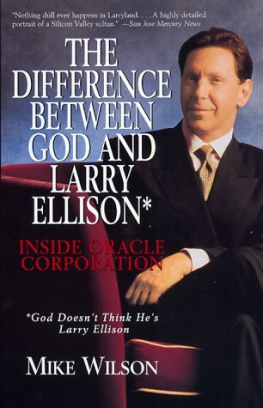

There are many people without whose help and advice this book could not have been written. Above all, Im grateful to Larry Ellison, whose enthusiasm and commitment never wavered even after it became clear that the story would not only have its share of twists and turns but would have a conclusion somewhat less clear cut than he had hoped. My thanks also to Melanie Craft, who bore with fortitude my invasion of her and Larrys privacy. Very many Oracle executives, both past and present, gave freely of their time and thoughts. Its not possible to mention everyone; they know who they are, and they are quoted in the book. But with Mark Jarvis, Jeff Henley, Safra Catz, Mark Barrenechea, Jay Nussbaum, and Ron Wohl I enjoyed a kind of extended conversation over a period getting on for two years. I was continually struck by the frankness and openness of those working for Oracle today, even when it came to talking about their boss. I would also like to record my thanks to Ray Lane. He understood that my relationship with Ellison was collaborative, but he still consented to be interviewed on two occasions, each time for several hours. He may not realize it, but he still has some good friends at Oracle. I also want to mention Joshua Lederberg, Steve Jobs, Jimmy Linn, Jon Bannenberg, and Laura Seccombe, who, in their different ways, gave me insights into Ellisons life that were unique. I must thank, too, those who helped me in practical ways, in particular Joyce Higashi, Carolyn Balkenhol, and Judy Sim. Without them there really would have been no book. I should pay tribute to my literary agent, Andrew Wylie, and my editor at Simon & Schuster, Geoff Kloske. From the outset, Andrew helped shape and define the project and continually buoyed me with his confidence and support; Geoff honed, tightened, and, where necessary, discreetly made me intelligible to Americans. Finally, my thanks to Bill Emmott, the editor of The Economist, who graciously allowed me a years leave to pursue this project and whose imaginative suggestion in 1997 that I should write about the unfolding drama of the Internet led directly to my meeting Larry Ellison.

AUTHORS NOTE

In March 2000, I received a telephone call from Larry Ellison. He had an idea for doing a book about e-business and globalization and wanted to know if I would be interested in coauthorship. I was flattered, but it wasnt something I wanted to do for a number of reasons. In the first place, a relationship with Ellison of that kind would mean I would have to give up writing about the technology business for The Economist because of the potential for conflict of interest. Second, I had no desire to add to the torrent of indifferent books about the e-business phenomenon that were then flooding the business publishing market. Third, although we shared many views and I had grown to like Ellison and enjoy his company in the brief time I had known him, I thought that coauthoring a book with him would be a nightmare.

But while we were talking, a much more appealing proposition began to form in my mind: what I would be interested in doing was writing an intimate portrait of Ellison and his company on the basis of having a very high degree of access to both him and Oracle. I explained that I would have to have complete editorial control and that it might be some time before I could take leave of absence from The Economist. Ellisons answer was immediate: hed love me to do it, and he was prepared to wait until I was ready.

Nine months later, in December 2000, accompanied by my New Yorkbased literary agent, Andrew Wylie, I met with Ellison at his Japanese-style villa in Atherton, a leafy and very expensive suburb some twenty miles to the southwest of San Francisco that is home to much of the Silicon Valley establishment. The meeting had three purposes. First, I needed to establish the basis of my working relationship with Ellison: Wylie had concluded that there should be a formal collaboration agreement between us. Second, although Ellison and I had recently discussed the book over dinner at my house in London, I did not yet have a settled idea of what it should be, although I had already ruled out doing a conventional biography. I knew that if the project was to engage Ellison it would have to be relevant to his current concerns. Most of all, I wanted to test Ellisons claim that Oracle was poised for true greatness.

One of the things I had noticed while covering the technology business was that many of its key players had extraordinarily little interest in even the recent past. It was as much as most of them could do to remember what it was that Microsoft had done to end up in court. Even Marc Andreessen was much keener to talk about the new businesses he was investing in than his epic struggle against Bill Gates while at Netscape. His attitude was: been there; done that; move on. When Microsofts witnesses were confronted with damning e-mails theyd written only a couple of years before, it is just possible their surprise and struggle to guess what they might have meant at the time wasnt completely phony. Ellison doesnt suffer from that kind of amnesia, but even though he reads history voraciously and tries to learn from it, what really interests him is not the last five years but the next five. To Ellison, the present and the near future elide so gracefully as to be almost indistinguishable. And when talking about software, last year is another country.

A collaboration agreement that gave me everything I would need was quickly reached. An innovative twist, devised by Andrew Wylie, was that Ellison would have a kind of right of reply or commentary within the book, which he could use either to express a counterpoint to any of my conclusions that he disagreed with or to amplify things that he thought important. Neither of us would be able to alter the words of the other. It is a unique form of joint copyright. I think it has worked.

There is one other thing I would like to say about my relationship with Ellison. In the course of my research, I met, somewhat to my surprise, a number of people who assumed that Ellison was paying me to write what he hoped would be a sympathetic account of his life. This is not the case. My compensation and expenses have been covered in full by the advance from my publisher. That said, I have stayed as his guest during my many visits to Oracle and have traveled with him on his private planes. I have also spent time with Ellison on his boats, recording extensive interviews during his vacations and, most recently, joining him in Auckland to report at first hand on his Americas Cup campaign. Has this degree of intimacy undermined my ability to be objective about Ellison? It is hard for me to say, but I dont believe so. I like Ellison and there is much about him that I admire, but I am frequently critical of him. Most of us, I think, are able to reach reasonably objective judgments about even our closest friends. Liking them does not mean being oblivious to their faults. I have written the truth about Ellison as I have found it and reported faithfully, for better or ill, the words of the many people who know him whom I have interviewed. When Ellisons version of events appears questionable or his behavior less than admirable, I have said so. But to a great extent, the picture of Ellison that emerges is one formed by his own words during innumerable, at times brutally frank, conversations conducted over a period of two years. Ellison is, more often than not, his own harshest and most unrelenting critic.

Next page