The column advanced rapidly considering the rough roads and the darkness, and from almost every wagon for many miles issued heart-rending wails of agony. For four hours I hurried forward on my way to the front [of the column], and in all that time I was never out of hearing of the groans and cries of the wounded and dying. Scarcely one in a hundred had received adequate surgical aid, owing to the demands on the hard-working surgeons from still worse cases that had to be left behind. Many of the wounded in the wagons had been without food for thirty-six hours. Their torn and bloody clothing, matted and hardened, was rasping the tender, inflamed, and still oozing wounds. Very few of the wagons had even a layer of straw in them, and all were without springs. The road was rough and rocky from the heavy washings of the preceding day. The jolting was enough to have killed strong men, if long exposed to it. From nearly every wagon as the teams trotted on, urged by whip and shout, came such cries and shrieks as these:

O God! Why cant I die.

My God! Will no one have mercy and kill me?

Stop! Oh! For Gods sake, stop just for one minute; take me out and leave me to die on the roadside.

I am dying! I am dying! My poor wife, my dear children, what will become of you?

Some were simply moaning; some were praying, and others uttering the most fearful oaths and execrations that despair and agony could wring from them; while a majority, with a stoicism sustained by sublime devotion to the cause they fought for, endured without complaint unspeakable tortures, and even had words of cheer and comfort to their unhappy comrades of less will or more acute nerves.... Except for drivers and the guards, all were wounded and utterly helpless in that vast procession of misery. During this one night I realized more of the horrors of war than I had in all the two preceding years.

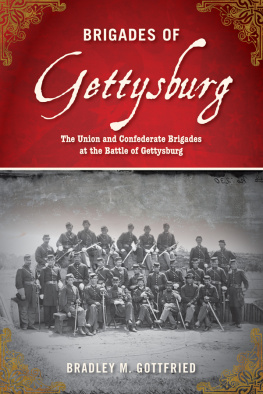

So wrote Brigadier General John D. Imboden, of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, to whom Robert E. Lee had assigned the wagon train of Confederate wounded after the Battle of Gettysburg, July 1-3, 1863.

That spring, the American Civil War had entered its third year. Few had expected it to last beyond a single summer. Back in the winter of 1860-61, when seven Southern states proclaimed their independence in the wake of Abraham Lincolns election to the presidency, it had become clear that the sectional feuding over slavery and its future had finally boiled over into a full-fledged crisis. Not waiting to see what policies this Black Republican might propose, the seven seceded states amalgamated to form the Confederate States of America in February, and in April, Lincolns call for troops to suppress this illegal assembly after the firing on Fort Sumter provoked four more states to join the Confederacy. Even then, few anticipated what lay ahead.

In July 1861, the armies of the two sides clashed along the banks of Bull Run Creek in northern Virginia in what some had expected - or at least hoped - would be the battle that decided the war. Instead, it provided only a glimpse of the carnage that would last four years and claim some 600,000 lives. Since that first engagement, armies from the two sides had met in Missouri, in Tennessee, in Kentucky, all across Virginia, and even in Maryland along the banks of Antietam Creek near Sharpsburg. Thousands had died; thousands more had been horribly wounded; even more had died of disease in the camps. Despite this appalling sacrifice, the end seemed no nearer. Lincoln called for 300,000 volunteers, then 300,000 more. The Confederacy, with its smaller population, instituted a draft obligating all white males ages eighteen to thirty-five to serve in the army. Then it raised the age limit to forty-five. Before the war was over, the draft would encompass all males ages seventeen to fifty.

Each side had underestimated the willingness of the other to sacrifice. Some sense of that permeated both sides in the spring of 1863. In Mississippi, a Confederate army under John C. Pemberton held a Union army under Ulysses S. Grant at bay outside Vicksburg; in Tennessee, another Confederate army under Braxton Bragg vied with a Union army under William S. Rosecrans for control of that state; and in Virginia, where most of the political and international attention was focused, Robert E. Lees Army of Northern Virginia faced a reinforced and revitalized Army of the Potomac along the banks of the Rappahannock River. Before the summer was out, Grant would have Vicksburg, Rosecrans would maneuver Bragg out of Tennessee, and the Army of the Potomac would win the most celebrated victory of the war near the small Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg.

These Union victories did not end the war, but they made it evident that the South could no longer hope to win the war on the battlefield. It would take a collapse of Northern will or outside intervention to conjure a Southern victory now. In that respect, the Union victories in the summer of 1863 were decisive, and none more so than the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in July 1863.

Fully a third of the 150,000 men who fought there became casualties. No one in the secession summer of 1861, even in his darkest nightmares, could have imagined such losses. None could have foreseen the moving horror that John D. Imboden encountered on July 5 when he rode out on Chambersburg Pike, along which the Southern army had advanced so confidently only five days before.

As heartbreaking as were the cries and shrieks of the wounded, they were deafened by the mute testimony of the thousands more who lay dead on the field. One of them was thirty-three-year-old private Amos Humiston of Oswego, New York. Humiston had spent several years as a merchant seaman before marrying Philitida Ensworth, a twenty-four-year-old widow, on the Fourth of July in 1854. Since then, they had had three children: a boy and two girls. Humiston had not enlisted in the first heady days after Fort Sumter. He was, after all, a husband and a father. But in July 1862, in response to Lincolns call for 300,000 volunteers in the wake of McClellans failed campaign on the Virginia peninsula, Humiston joined a local company that became part of the 154th New York volunteers. Like most soldiers on both sides, he wrote regularly to his wife, thus leaving a record of his experiences in the field. His homesickness was palpable. In December, he wrote: I would give all most any thing if I could make you a good long visit and be back here again but that can not be but when I do come those red cheeks will get kissed more than once I can tel you. How I would like to be with you Christmas and new years and [enjoy] one of your diners again and have the babies on my knee to hear them prattle as they used to. This war can not last for ever it does seem to me.

Two days after the Battle of Gettysburg, Humistons body was found near the town brickyard at the foot of Cemetery Hill. Soldiers wore no dog tags in those days; the only clue to his identity was a photograph he held in his lifeless hands of his three children. News of this heartrending scene was printed in several Northern newspapers, but not until November, the same month that Abraham Lincoln traveled to Gettysburg to dedicate the National Cemetery, did Philinda see the story. She was a widow again.

Another who lay mute on the battlefield was Colonel Isaac Avery of North Carolina. Avery had come north as the temporary commander of what was generally known as Hokes brigade. Hoke was still recovering from a wound when the Southern army went north into Pennsylvania, so Avery, as the senior colonel, assumed command. A big, bluff, sandy-haired man, Avery was imbued with the ideals and values of his time and place. For him, duty and honor were the indispensable elements of manhood. On the second day of the Battle of Gettysburg, he led his command in a twilight charge up Cemetery Hill. In the smoke and confusion of the charge, no one noticed when he fell from his horse, shot in the throat. His men swept past him. Alone in the dark, he fumbled for a piece of paper and a pencil and scribbled out a short note for his friend Major Sam Tate, Major, Tell my Father I died with my Face to the enemy. I. E. Avery. He was still holding that note when his body was discovered less than a hundred yards from Humistons.