Craig L. Symonds

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

Craig L. Symonds 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Names: Symonds, Craig L., author.

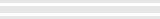

Title: World War II at sea : a global history / Craig L. Symonds. Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2018] |

Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017032532 | ISBN 9780190243678 (hardback : alk. paper) ebook ISBN 9780190243692

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19391945Naval operations Classification: LCC D770 .S87 2018 | DDC 940.54/5dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017032532

The second world war was the single greatest cataclysm of violence in human history. Some sixty million people lost their livesabout 3 percent of the worlds population. Thanks to scholars and memoirists of virtually every nation, it has been chronicled in thousands, even hundreds of thousands, of books in a score of languages.

Many of those books document the naval aspects of the war. Unsurprisingly, the winners have been more fulsome than the vanquishedStephen Roskill and Samuel Eliot Morison emphasized the particular contributions of the Royal Navy and the United States Navy in multivolume sets. Others have examined the role of navies in a particular theater or a particular battle, especially in the Mediterranean and the Pacific. Yet no single volume evaluates the impact of the sea services from all nations on the overall trajectory and even the outcome of the war. Doing so illuminates how profoundly the course of the war was charted and steered by maritime events.

Such is the ambition of this work, and it is one with challenges. The story of the global war at sea between 1939 and 1945 is a sprawling, episodic, and constantly shifting tale of conflicting national interests, emerging technologies, and oversized personalities. Telling it in a single narrative is daunting, yet telling it any other way would be misleading. There was not one war in the Atlantic and another in the Pacific, a third in the Mediterranean, and still another in the Indian Ocean or the North Sea. While it might simplify things to chronicle the conflict in such geographical packets, that was not the way the war unfolded or the way decision-makers had to manage it. The loss of shipping during the Battle of the Atlantic affected the availability of transports for Guadalcanal; convoys to the besieged island of Malta in the Mediterranean meant fewer escorts for the Atlantic; the pursuit of the battleship Bismarck drew forces from Iceland and Gibraltar as well as from Britain. The narrative here, therefore, is chronological. Of course, leaping about from ocean to ocean day to day is both impractical and potentially bewildering, so there is necessarily some chronological overlap between chapters.

Whenever possible, I allow the historical actors to speak for themselves, for my goal in this book is to tell the story of World War II at sea the way contemporaries experienced it: as a single, gigantic, complex story, involving national leaders and strategic decision-makers, fleet commanders and ship drivers, motor macs, gunners, pilots, merchant seamen, and Marines; as a worldwide human drama that had a disproportionate and lasting impact on the history of the world.

London, 1930

The murmur of conversation ceased abruptly and there was a rustle of movement as the assembled delegates stood when King George entered the Royal Gallery, followed by the lord chamberlain and the prime minister. The king walked slowly but purposefully toward the ornate throne that dominated one end of the House of Lords, and he waited there while the delegates resettled themselves. That he was here at all was noteworthy, for George V had been ill for some time (very likely with the septicemia that would later kill him) and had retired to Craigweil House, in Bognor, on the Sussex coast, to recuperate. Unhappy and frustrated by his confinement there, he had made a special effort to be present for this ceremony.

The House of Lords, with its gilded coffered ceiling and stained glass windows, offered a suitable stage for the kings public reappearance, though the windows admitted little light on this occasion because on January 20, 1930, London was blanketed by a thick fog; local authorities had been compelled to turn on the streetlights in the middle of the day. The hall was crowded, not with peers of the realm, but with more than a hundred delegates from eleven nations. Six of those nations were dominions within Britains far-flung empire, including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, though the audience also boasted representatives from the military powers of three continents. From Europe there were delegates from both France and Italy (though, significantly, not from either Weimar Germany or communist Russia). In addition to Canada, a delegation from the United States represented the Western Hemisphere, and from Asia there was a substantial contingent from the Empire of Japan, though not from China. Each delegation was headed by a high-ranking civilian, and the audience included two prime ministers, two foreign secretaries, and one secretary of state. The menand they were all menwere mostly in their fifties and sixties, and they constituted a somber audience in their dark suits with stiff white collars.

Scattered among them, however, and lined up across the back of the hall, were the uniformed officers of a dozen navies, the fat and narrow gold stripes ascending their sleeves from cuff to elbow revealing their exalted rank. There was less variation in their attire than might have been expected from such a polyglot assemblage because all of them, including the Japanese, wore uniforms modeled on the Royal Navy prototype: a double-breasted dark blue (officially navy blue) coat with two vertical rows of gold buttons. Here was unmistakable evidence of the extent to which the Royal Navy was the archetype of all modern navies.

Many of the officers also wore gaudy decorationsstars and sashesearned over a lifetime of service at sea and ashore, and the bright splashes of color among the dark suits suggested songbirds among ravens. Even the junior officers, tasked with note-taking, translating, and providing technical support, stood out by sporting thick aiguillettes of gold braid draped over their shoulders and across their chests, ornamentation that identified them as belonging to the staff of one or another of the gold-striped admirals.

Contents

Contents