Alexandra Zapruder - Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust

Here you can read online Alexandra Zapruder - Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2015, publisher: Yale University Press, genre: Non-fiction / History. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust

- Author:

- Publisher:Yale University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2015

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Klaus Langer

Courtesy of the Langer family archive

Klaus (later Jacob) Langer was born on April 12, 1924, in the city of Gleiwitz, in Upper Silesia, which at that time was part of Germany. His father, Erich, had also been born in Gleiwitz; his mother, Rose, was born in Odessa and emigrated to Germany in 1912, where she and Erich Langer married in 1922. Klauss grandmother, Mina, joined the family in 1927, when he was three years old. After successive moves from Gleiwitz to Wiesbaden, then to a small town near Gelsenkirchen, the family settled in Essen in 1936.

Klaus began his diary in his native German shortly after his , and was living at home with his parents and grandmother as he always had done. Despite signs of instabilitythe emigration of many of his Jewish friends and the occasional restrictions against Jews (closing of Jewish-owned businesses and prohibitions against Jews attending the public pool)the Langers were still living in a relatively recognizable world.

Much of the early part of Klauss diary was devoted to recounting the events, activities, and discussions held in the Zionist youth group of which he was a part. Group meetings focused largely on discussions, often oriented toward distinctly modern and nontraditional topics, among them Zionism, assimilation, anatomy, modesty, and sex. Most central to the movement, however, was preparation for emigration to Palestine. Because life there was geared toward building Jewish settlements, there was an emphasis on outdoor activities, nature, and, above all, communal existence and agricultural and manual labor.

Klauss involvement in the Zionist youth movement gave rise to a faint but unmistakable tension with his father that emerges in the diary. Klauss family was an archetypal German Jewish one, having had a long history of residence in Germany. His father had fought on the French front in World War I, joining the German army as a volunteer in 1915. After the war, he went on to become a judge in the German court system. Like many German Jews of that generation, he and his family were nationally, culturally, and socially embedded in mainstream German civilization. For Erich Langer in particular, who had successfully assimilated into German society, the culture of the Zionist youth movement was diametrically opposed to everything he envisioned for his son. Life as a pioneer among Jews in an underdeveloped country, living in communal dwellings and performing physical labor, was seen as a step backward, a loss of the very entitlements he had struggled so hard to achieve. It was for this reason that he was reluctant to allow Klaus to immerse himself in the youth group, and only permitted him to attend meetings if he did not neglect his studies and his music.

Klauss relatively normal life came to a crushing halt with Kristallnacht, the Nazi attack on synagogues, homes, businesses, and private property of Jews in cities throughout Germany and Austria on November 9 10, 1938. It was a dramatic turning point in the history of Germanys Jews, a shocking display of violence in which the property of Jews was destroyed, their synagogues burned, and their businesses vandalized. Klauss longest and most detailed diary entry is about As Klaus recorded in his diary, his father was among those arrested in Essen.

Kristallnacht, for the Langer family as for many German Jews, signaled the severity of the situation as no previous passage of laws or decrees had done. The gradual escalation of restrictions, humiliations, and exclusions had culminated in an unexpected and drastic pogrom reminiscent of those perpetrated on Jews in the Middle Ages. Further, a new onslaught of decrees followed Kristallnacht, almost completely limiting the movement and freedoms of Germanys Jews. Among them were the orders expelling all Jewish children from German schools and banning Jewish youth group activities.

For the Langer family, Kristallnacht served as a powerful catalyst for emigration. Ultimately, this is the main subject of the diaryemigration itselfand the familys increasingly desperate efforts to get out. I can sing a song on that subject, Klaus wrote dryly on January 14, 1939. His diary entries reveal the overwhelming difficulties and bureaucratic mazes that faced those trying to flee. The Langers tried to find safe passage to Chile, India, Palestine, Holland, the United States, the Dominican Republic, Peru, Uruguay, Shanghai, Argentina, and England; each try was met with evasions, further requirements, or outright refusals. Further, Klaus listed in his diary the various paper wallspersonal papers, physical exams, travel documentation, employment assurances, visas, affidavits, and letters of creditthat made emigration virtually impossible.

Klauss diary captured the excruciating recurring cycle that plagued would-be emigrants. It began with a hopeful lead, the frantic gathering of materials, promises, assurances, packing, and then, ultimately, seemingly inevitably, the plan would collapse, undermined by a technical detail or a missed deadline. Klauss diary entries, filled as they are with requirements, regulations, and restrictions, seem to mirror the confusion and bureaucratic entanglements of the process itself. His personal story typified that of hundreds of thousands of German Jews who were faced with the fact that throughout the 1930s, few European countries eased quotas, lifted restrictions, or simplified existing procedures to allow for Jewish emigration. As a result, many families who were willing to emigrate found that they This failure on the part of the European nations and the Americas, including the United States, resulted in the entrapment of hundreds of thousands of families in Germany. Beginning in the fall of 1941, these individuals and families were deported to ghettos and concentration camps in the German-occupied Eastern territories.

While much of the diary is filled with the pragmatic details of the Langers search for a safe haven, there are traces in the diary that reveal a still deeper issue that also lay at the root of the emigration process. Beyond how the Nazis approached the problem, how the European nations addressed it, or even how the individual families attempted to maneuver within the bureaucracy, there remained the question of how assimilated Jews like the Langers understood themselves and their place in the world, and consequently how quickly, efficiently, and aggressively they attempted to flee. In the case of the Langers, they deliberated over where they should go, weighing such matters as the transfer of Erich Langers pension and the likelihood of finding work, rejecting potentially viable opportunities in their quest for the best choice. Further, there are subtle clues in the diary that suggest how difficult it was for the Langers to fully accept their altered circumstances and to comprehend the nature of the move that confronted them. In particular, Klaus on occasion seemed to view the matter of preparing for emigration as if he were moving to another country by choice, rather than fleeing for his life. Most notably, he calmly made preliminary arrangements to bring such impractical items as an old typewriter, his bicycle, his cello, and even the familys grand piano with him in exile.

These allusions, faint as they might be, suggest the depth of the Langers ties to established German society. For even as they faced the once unthinkable question of leaving Germany and accepted the necessity of flight, that stubborn rootthe image they had of themselves in the worldremained at least partially intact and entrenched. These last ties were not only a tragic illusion in the context of Nazi Germany but were, in some cases, another impediment to emigration itself, as people unwittingly delayed, deliberating over choices and exercising rights that were no longer theirs. The truth, which is easy to see in retrospect but was incomprehensible to many at the time, was that emigration was not a choice, it was an imperativethe last hope to escape unharmed as Germany unraveled, bringing the rest of Europe with it.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

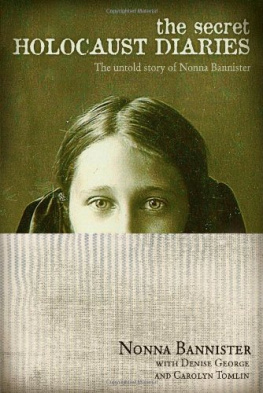

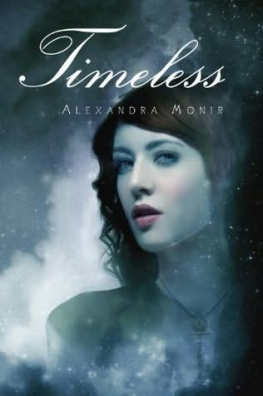

Similar books «Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust»

Look at similar books to Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Salvaged Pages: Young Writers’ Diaries of the Holocaust and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.