Contents

Guide

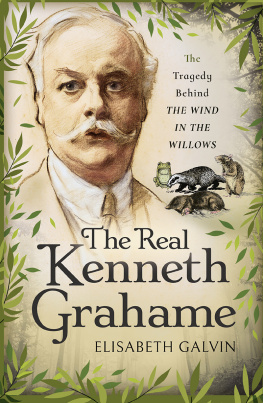

BY THE SAME AUTHOR:

The Last Princess: The Devoted Life of Queen Victorias

Youngest Daughter

Empress of Rome: The Life of Livia

The Twelve Caesars

Queen Victoria: A Life of Contradictions

Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West

Over the Hills and Far Away: The Life of Beatrix Potter

The First Iron Lady: A Life of Caroline of Ansbach

T HE M AN IN THE W ILLOWS

Pegasus Books, Ltd.

148 West 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2019 by Matthew Dennison

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition February 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: is available

ISBN: 978-1-64313-007-1

ISBN: 978-1-64313-097-2 (ebk.)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

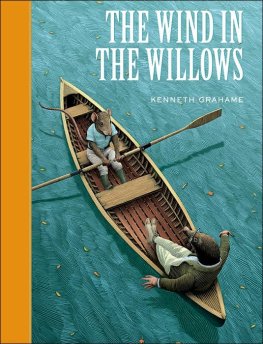

For my father, who loves The Wind in the Willows and boats and the sea

What the Boy chiefly dabbled in was natural history and fairy-tales, and he just took them as they came, in a sandwichy sort of way, without making any distinctions; and really his course of reading strikes one as rather sensible.

Kenneth Grahame, The Reluctant Dragon

Contents

I F WE IMAGINE Kenneth Grahame as a child as he described himself, he is doodling in the margins of a book. It is 1866 or thereabouts and he is seven years old.

He draws crocodiles of jagged outline and spear-bearing African tribesmen, licking the lead of his pencil to make each mark decisively black. He draws monkeys gibbering with terror, swarming up palm trees, and admits that an oak tree is beyond his skills. Most of the books he decorates are histories of the ancient world. He singles out Macaulays Lays of Ancient Rome , a Victorian schoolroom staple. Afterwards his doodles are imprinted on his mind more vividly than Hannibals stirring triumphs or the ornate set speeches of Roman generals, whose voices powerless to pierce the distance of time echo thin and faint. His pencil prefers exotica. In place of centurions or legionary banners he draws the more attractive flesh and blood of animal life, the varied phases of tropic forest. He note[s], cite[s], and illustrate[s] the habits of crocodiles.

Like his pencil, his mind wanders with a boys unruly imagination. He amuses himself playing games with words. By this single battle of Magnesia, Antiochus the Great lost all his conquests in Asia, he reads, and he substitutes bottle for battle. Some margins he leaves blank. The white spaces are clear sky ever through which I could sail away at will to more gracious worlds in the words of his river-and boat-loving adult self.

At the same time the young Kenneth comes across an old-fashioned atlas. Its maps include empty passages where the mapmakers knowledge has run out. Later he described these voids lingeringly, remembering the excitement of first encounter: broad buff spaces unbroken by the blue of any lake, crawled upon by no mountain ranges.

Dark-haired, pale-faced and short for his age, Kenneth Grahame was an imaginative child; he became an imaginative adult. He continued to invent golden realms into old age; he let his thoughts take wing, and the playfulness of those thoughts remained boyish. As the highest expression of the emotion of Joy, we would all of us naturally choose to spring upon a charger and ride forth into the boundless prairie, he wrote in 1925, at the age of sixty-six.

Imaginative escape moulded Kenneth Grahames childhood. It found expression in the scribbled margins of books and swashbuckling games played out in his head under the influence of Ballantynes The Dog Crusoe and His Master , a story of prairie settlers, Aesops Fables or newly published descriptions of the Nile by explorer Samuel Baker. Afterwards it dominated his memories. It provided threads of narrative that he pursued in his writing as well as his interior life, and the excitement of childish adventure and childhood stories never palled for him. He was a quiet child. When, seldom, he sat for a photographer, he appeared earnest or bored, and nothing of his heroic self-fashioning showed in his startled, blank gawping so typical of early photographs, with their long exposures and enforced stillness. Hard to trace in that unrevealing gaze traces of the small boy [thrust] out under the naked heavens to enact a sorry and shivering Crusoe on an islet in the duck-pond or so consumed by excitement at the prospect of a circus that he longs to escape into the open air, to shake off bricks and mortar, and to wander in the unfrequented places of the earth, the more properly to take in the passion and the promise of this giddy situation.

In an essay called Long Odds, he recalled his six- or seven-year-old self. He depicted a boy of fluid identity, able to shape-shift at will. The boy is so absorbed in fantasy that he becomes his fictional hero. In the person of his hero of the hour [he] can take on a Genie a few Sultans and a couple of hostile armies, with a calmness resembling indifference. Both boys stories include fragments of self-portrait: Kenneth Grahame was that boy at six and at ten and, in imagination, ever after.

As a child in cloudland he circled the globe like Puck, or like the part-fictionalized boys of his stories, or in his other guise of crocodile-doodling reader. He always came home. Ideas of escape and homecoming, twinned from childhood, mark the pendulum swing of his mind. They shape his only full-length fiction, The Wind in the Willows . Doggedly he embraced his own parallel universe as a reality and sugared it with guarantees of a safe return. In a similar way, in The Odyssey , a poem Kenneth Grahame knew well and plundered in The Wind in the Willows , Homer tempers the readers experience of Odysseuss terrifying exploits with assurances of his fated homecoming. The certainty of a safe return as a corollary to escape, the world shut out the ideal encasement, as Kenneth described it, was one source of happiness in his fragmented, peripatetic, orphaned and exiled childhood.

And childhood happiness is not least among the surprises of his life.

He began well enough, with what he afterwards labelled a proper equipment of parents.

Kenneth Grahame was born on 8 March 1859, in Edinburgh. 32 Castle Street was, as it remains, foursquare and handsome. Generous in its proportions, restrainedly neoclassical, it is typical of domestic architecture in Edinburghs New Town. Shallow steps rise to a front door topped by an elegant but simple fanlight. Glazing bars neatly bisect tall windows. The house is built of granite the colour of watercolour shadows. Kenneths first biographer places an almond tree outside it. Its branches stretch tight-furled buds towards first-floor windows. The same author, harried by Kenneths fanciful widow, furnishes those branches retrospectively with a single bird, a thrush from nearby Princes Street Gardens. Inevitably it heralds the new arrival in song.