Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2014 by J. Grahame Long

All rights reserved

First published 2014

e-book edition 2014

ISBN 978.1.62584.549.8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Long, J. Grahame.

Stolen Charleston : the spoils of war / J. Grahame Long.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

print edition ISBN 978-1-62619-096-2

1. Charleston (S.C.)--History--1775-1865. 2. Pillage--South Carolina--Charleston--History. 3. Charleston (S.C.)--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Destruction and pillage. 4. Charleston (S.C.)--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Destruction and pillage. 5. United States--History--Revolution, 1775-1783--Destruction and pillage. 6. United States--History--Civil War, 1861-1865--Destruction and pillage. I. Title.

F279.C457L66 2014

975.791503--dc23

2014021494

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

For Lissa

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

While there are some things that can be accomplished alone and unaided, this book is in no way one of them. I wish to express my tremendous thanks to the following for their help and support:

John Young, assistant director, the Powder Magazine; Frank Justice; Lauren Northup, museum manager, Historic Charleston Foundation; Mary Edna Sullivan, curator, Middleton Place Foundation; Phillip Middleton; Bru Izard; Lee Manigault; Louisa Montgomery; Keith Leonard; Robin Rice; Matt and Susan Verdery; W.B. Chisolm Leonard, parish administrator, St. Philips Episcopal Church; Brain Fahay, archivist, Catholic Diocese of Charleston; Cheralaine Dougherty, parish administrator, Christ Church; Charlotte Crabtree; Reverend Daniel Massie, pastor and head of staff, First (Scots) Presbyterian Church; Jeff Ball; Robert Ball Jr.; Gillian Bagley, parish administrator, Church of the Good Shepherd; Lieutenant Charles Fazio, curator, Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company; the MacMeekin family; and Don Horres, executive director, Mount Pleasant Presbyterian Church.

Of course, the outstanding and dedicated staff at the Charleston Museum, especially director Carl Borick, graphic designer and photographer Sean Money and archivist and collections manager Jennifer McCormick. As always, to my family for their enthusiasm, faith and extreme patience.

I

ELEGANCE LOST

On January 24, 1945, a package arrived with the daily mail at the Christ Church on Rutledge Avenue and immediately caught the eye of Reverend Edmund Coe. While not unusual for a busy church, this particular Illinois-postmarked parcel delivery was eagerly anticipated. Within the neatly packed box was a large coin-silver vessel with a small lamb finial on the hinged top. The makers mark on the bottom denoted the pieces Charleston artisan, John Ewan, a silversmith and jeweler from 1823 to 1852. Although Reverend Coe had carried on some previous correspondence with the parcel sender, nothing could have prepared him for this moment. After eighty years, the Christ Church flagon was home.

In her first communication with Reverend Coe some weeks earlier, Mrs. Bonnie McArty had explained how she and her family made their embarrassing discovery. We were doing some work on our home, she wrote, and came across [the flagon] and thought I would shine it up. Well, that is the first we knew it had any inscription on it. Believing the piece not rightfully theirs, McArtys letter further made an earnest plea to Reverend Coe, hoping he and the rest of the church might forgive her uncle, Frank Blaine, a Union infantryman in Charleston after the 1865 Confederate evacuation. It seemed that Blaine, a very young boy at the time, stole the flagon from a deserted church and brought it home. Only long after his death had it been discovered by his descendants, who were now determined to set things right and return the ill-gotten war prize after so many years.

Coin-silver flagon (marked by Charleston silversmith John Ewan circa 1840) taken from Christ Churchs Rutledge Avenue location in 1865 and returned to Charleston in 1945. Courtesy of the Church of the Good Shepherd, Charleston; photo by Keith Leonard.

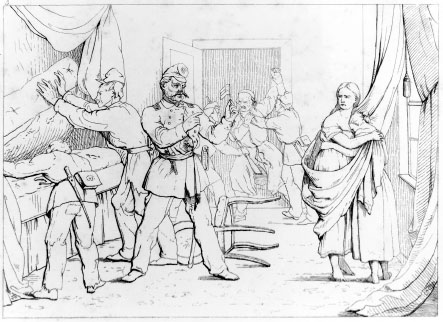

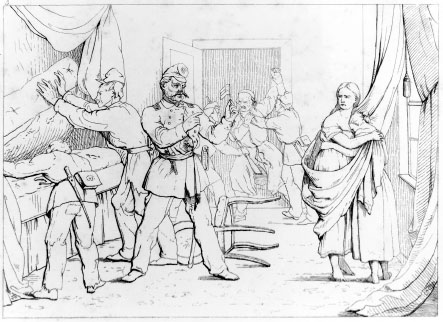

Searching for Arms by Adalbert John Volck, circa 1890. Library of Congress.

As surprising as it may be that one of Charlestons artifacts actually made it home, the sheer fact that it went missing during wartime is anything but. Charleston has scarcely been a stranger to hardship. Devastation has seemingly always been close at hand. Among various calamities, Charleston is the rare American city that had two wars fought on its own soil, each resulting in heavy artillery sieges and subsequent enemy occupations. Expectedly, alongside these intrusions arrived soldierly lawlessness on a grand scale.

Practically everyone in Charleston seems to have at least one old family tale involving run-ins with the enemy and the heirlooms they took away. Even today, the American Revolution and Civil War together are believed by many to be the single greatest cause for the disappearance of old pieces. Based solely on these oral histories, then, it would appear that neither church, home nor citizen was immune to the incomparable losses brought by wars encroachment on the Charleston home front.

When examined from a historical perspective, wartime plundering is not exactly hard to find among city and state records. In fact, it is hardnigh impossibleto name any war in all of human history that has occurred without some form of soldierly pillaging once within the enemy home front. For that reason, then, was it not bound to happen in Charleston as a mere accompanying element of warfare? Indeed, wartime raiding and plundering is as old as even the most basic concept of conquest. To the victor go the spoils! proclaimed Senator William L. Macy in 1832, an utterance that still finds adherents in any number of todays war-riddled locales. Allusions in classical literature are abundant as well. Tolstoy, Hugo and Shakespeare each consistently referred to episodes outside of normal warfare, where looting and pillaging were considered a right. Mental images of historical combat victories from every era bring about evocations of confiscated, if not illicitly obtained, rewards. Indeed, how boring classical pirate lore would be if pillage and plunder were nonissues!

Looking back further among the ancients, pillage was not so much a perquisite as it was an actual strategy by which vanquishers further degraded their enemies. So what if an opponent was defeated on the battle front? They must be soundly crushed on the home front as well by having their possessions or perhaps even themselves seized as war booty. As Isaiah attests in the Old Testament, This is a people plundered and looted, all of them trappedThey have become plunder. As time marched on, of course, the universally understood notion of wartime spoils took on a somewhat newer principleor at least one with a more important cultural usage. That is, merchandise and other valuables became necessary. For example, Genghis Khan, perhaps the greatest war looter the world has ever known, not only acquired plunder but also controlled it, masterfully redistributing it to his raiders as collective income and thus further motivating his troops by making great promises and glowing representationsin respect to the booty to be obtained.

Next page