This edition first published in hardcover in the United States in 2013 by The Overlook Press, Peter Mayer Publishers, Inc.

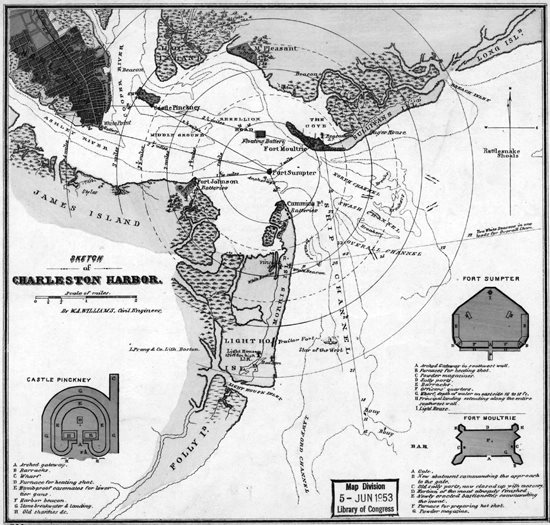

The portrait of John England on page 9 of the insert is courtesy of the Catholic Diocese of Charleston. All other illustrations are courtesy of the Library of Congress or in the public domain.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, or broadcast.

The undated map above shows the defenses of Charleston Harbor at the start of the Civil War. Fort Wagner was built later near the narrowest point on Morris Island.

N O M ORE P EACE F OREVER

O n a March afternoon midway through the American Civil War, the rich and poor, white and black people inhabiting Charleston, South Carolina, the birthplace of Secession, trudged behind the coffin of James Louis Petigru, defender of the Union. All the interests and classes of Charleston, scientists, judges, politicians, and especially all the members of the Bar of this city paid their last respect to this tattered remnant of the United States. As they slowly made their way from the house where the old lawyer died to the graveyard next to St. Michaels towering steeple, their faces expressed the conviction that a great man had departed from this world. The cold of winter did him in. Corpulent and debilitated by chronic bronchitis, Petigru knew by February that he was dying. He had no blood relations left in the city, and his own house in the heart of town had burned to the ground two years earlier in the great Charleston fire, so he faded in a borrowed room of an old friends son, tinkering with his will before succumbing finally to the wintry cough.

Charleston was hardly in a mourning mood. Fruit trees along the coast had been blooming for two weeks. The grass was springing up everywhere, and the most beautiful lawns were growing on the sandbags that had been heaped up at the waterfront to protect the cannons that were protecting the city. The whiff of warmer days sweetened the breath of most of the white folks in the funeral cortege, and, while they listened with bowed heads to the beautiful and touching service, most minds probably drifted away from the venerable history of the

No one was left to question the positive good theory of slavery, the most destructive idea to come out of South Carolinas conservatism. It was a relatively young idea in 1860, having been born barely forty years earlier and entering its maturity no sooner than 1835. Like the totalitarian ideologies of the twentieth century, the ascendancy of the positive good theory required the parallel idea that political dissent is evil, and so South Carolina strictly regulated speech, beginning in 1832, spreading such repression until the American South, by the 1840s and 1850s, was little better than a police state. Though only one full generation of white southerners grew up under this regime, history has proven how much damage one generation can wreak.

In 1860, elder men and women could remember when times were different, and the aged Petigru reminded his fellow Charlestonians of an older way of thinking. He was a Whig when there was no longer a Whig party, and he belonged to the age when American statesmen from the South and the North tried to forge a common nation by compromise and friendship, an age when the best minds of the South openly regretted slavery and thought it would die a natural death in the new republic by growing more anachronistic with each passing generation. Petigru was a reliquary of what political discourse had been before the rise of southern unanimity, and to see him on the street was like looking at a museum curiosity, something that bemused but did not influence the confident and unreflecting young.

In the Revolutionary era, dissent was not so isolated and impotent. Just a month after the signing of the Declaration of Independence, Henry Laurens, a merchant from Charleston, declared:

I abhor Slavery, I was born in a Country where Slavery had been established by British Kings & Parliaments as well as by the Laws of that Country Ages before my existence. In former days there was no combating the prejudices of Men supported by Interest, the day I hope is approaching when from principles of gratitude as well as justice every Man will strive to be foremost in shewing his readiness to comply with the Golden Rule; I am devising means for manumitting many of [my slaves] & for cutting off the entail of slavery.

Laurens knew that great powers opposed him, not only the laws & customs of South Carolina, but his own and his countrymens greed. I am not one of those, he said, who dare trust in Providence for defence & security of their own Liberty while they enslave & wish to continue in Slavery, thousands who are as well intitled to freedom as themselves.

Unchecked greed had created slavery in Charleston almost from the moment of its founding, in 1670, and no one then had any illusions about it. Its earliest proponents knew slavery was a crime perpetrated against a conquered people, and the conquest of the earth, as Joseph Conrad reminds us, means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, [and] is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much robbery with violence, aggravated murder on a great scale. The first English settlers of Carolina knew the stain that slavery put upon their souls, but they ignored their own moral compass in the face of staggering profits. Yet, as time passed with each new generation, as more whites and more blacks were born into slave society and grew up in it, as the institution was creolized, it began to seem more and more natural. White men born into the slave system, whose wealth was dependent upon slavery but who were too genteel to see themselves as thieves, developed a paternalistic view of slavery, thinking of themselves as parents or custodians of the intellectual and moral development of the black people who had been degraded by earlier generations. Still, they understood that slavery was inimical to human nature, as the ideology of the American Revolution clearly indicated, and enlightened southerners looked forward to the time when this sin against liberty might be purged, when their black dependents might grow up and prove themselves worthy of self-determination. The contagion of liberty inspired patriots like Henry Laurens to imagine that the day might come sooner rather than later. He and other men of conscience knew that the commerce between master and slave is despotism. Thomas Jefferson presciently confessed in his Notes on the State of Virginia, I tremble for my country when I consider God is just, and his justice cannot sleep forever.

Few of South Carolinas aristocrats were ready to start manumitting their slaves, so Laurens knew that he was dissenting from the prevailing view. Nevertheless, this dissenter was a man of considerable influence. Laurens was the vice president of South Carolina when he declared his abhorrence of slavery; the following year he was president of the Continental Congress. He was the most prominent national politician south of Virginia, and one of the United States five delegates at the Treaty of Paris, which finally ended the war. Nor was he alone. A sizeable and voluble minority agitated for emancipation-friendly legislation, a faction at first led by Laurenss own son, a colonel in the Continental Army, John Laurens. In the generation following the Revolution, prominent planters, respectable men of business, and influential politicians could openly dissent and even discuss how to eradicate slavery in the chambers of government. They had many fellow travelers: before about 1820, no one in Charleston was willing to argue that slavery was a public good. And yet, not a single delegate to the 1860 Secession Convention in Charleston believed that slavery was evil. A remarkable consensus.