Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

For William and Mary Lou Kelly

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Americas Longest Siege: Charleston, Slavery, and the Slow March Toward Civil War

Our Joyce: From Outcast to Icon

CONTENTS

A storm at sea. Waves swelling higher than the ships deck and wind like an ax chopping off their caps and throwing water at the heavens. So much seawater in the air, it seems it will drown the lightning. The sky pours down stinking pitch, sulfurous smell, and thunder. A brave vessel full of noble creature[s] climbing the waves and sliding into the troughs, its seams barely holding together.

So opened Shakespeares Tempest in a cold London theater in the winter of 1611.

It was a true story. To use todays common language, Shakespeare ripped this scene from the headlines. Only there were no headlines in 1611. Newspapers had not been invented. The first English-language periodical, a weekly broadsheet, was printed ten years later, ironically enough in Dutch-speaking Amsterdam. News of great events circulated the streets of Englands towns in more entertaining, less dependable channels: pamphlets, sermons, songs, notices posted in town squares, private letters passed around from one reader to another. And rumor. Buzzing like the crowd noise preceding a play, the cacophonous, often contradictory, sailors stories seeped up from the docks of London, Southampton, and Plymouth. And plays, even those as fantastical as

This story of storm, wreck, and redemption was the talk of England. Although a century had passed since Columbus first crossed the Atlantic, the open sea still preyed on the sailors psyche in a way that coast-hugging Europeans had never felt. When a storm came on the western ocean, there was no chance of running to harbor. Voyagers were beyond the frontiers of civilization, encroaching on spaces unlit by Christianity, where dark forces reigned. Anything could happen.

At the height of Shakespeares play, a few noblemen come on deck demanding to speak with the ships master.

[Y]ou marre our labour, the boatswain answers. Keepe your Cabines: you do assist the storme.

The words sound like revolution. At least on the surface, the seaman seems to be a leveler who favors meritocracy over aristocracy.

You are a Counsellor, the boatswain tells Gonzalgo, if you can command these Elements to silence vse your authoritie: If you cannot out of our way I say.

Gonzalgo warns him, remember whom thou hast aboord.

None that I loue more than my selfe, replies the sailor. [W]hat cares these roarers for the name of King?

Such stuff might embolden the common sort to check their supposed betters. One might think so, until it is remembered that the common sort was not in the plays audience. The Tempest premiered in the elegant, enclosed Blackfriars Theatre. The more democratic and open-air Globe Theatre was always crowded with groundlings, who stood in the pit chewing their sausages. But tickets to the indoor, winterized Blackfriars Theatre were pricier. Londons aristocracy sat in their boxes dressed in finery, and the guildsmen and craftsmen and professionals, up to perhaps a thousand patrons, filled the rest of the audience. Rich though they were, they were as eager as any to see onstage what theyd heard about in rumor: what had happened to the Sea Venture .

The players wobble-strut on the stage as if on the heaving and tossing deck of that ship, while the master and boatswain shout instructions into the noise of the wind.

Take in the toppe-sale!

At all cost they must keep steerageway. They catch just enough wind to point her bow into those rising seas. If a wave should take them broadside, it might roll the top-heavy ship till the masts kissed the water, and she would not rise again.

Lay her a hold, a hold, set her two courses off to Sea again, lay her off!

All labor for naught! The ship does not roll but its very boards come apart, letting in the sea like a sieve. The scene ends with mariners flooding the stage, clothes dripping with salt water, crying in despair and fear: We split, we split!

Farewell my wife, and children, the sailors wail.

Farewell, brother!

Elizabethan theater might have skimped on props and sets and special effects when judged by the standards of our own blockbuster action films. It had to rely on the words of the actors to paint the scene. As Shakespeare himself put it, the breath of those who watched the play must fill the ships sails with wind. But Shakespeares words! They whipped up gales in the minds of the viewers. The patrons quaked under the shock of thunder and lightning.

A ship full of a hundred and fifty souls split at sea, in the midst of the most terrible storm, and yet every person lived! This was Englands most shocking, unbelievable news.

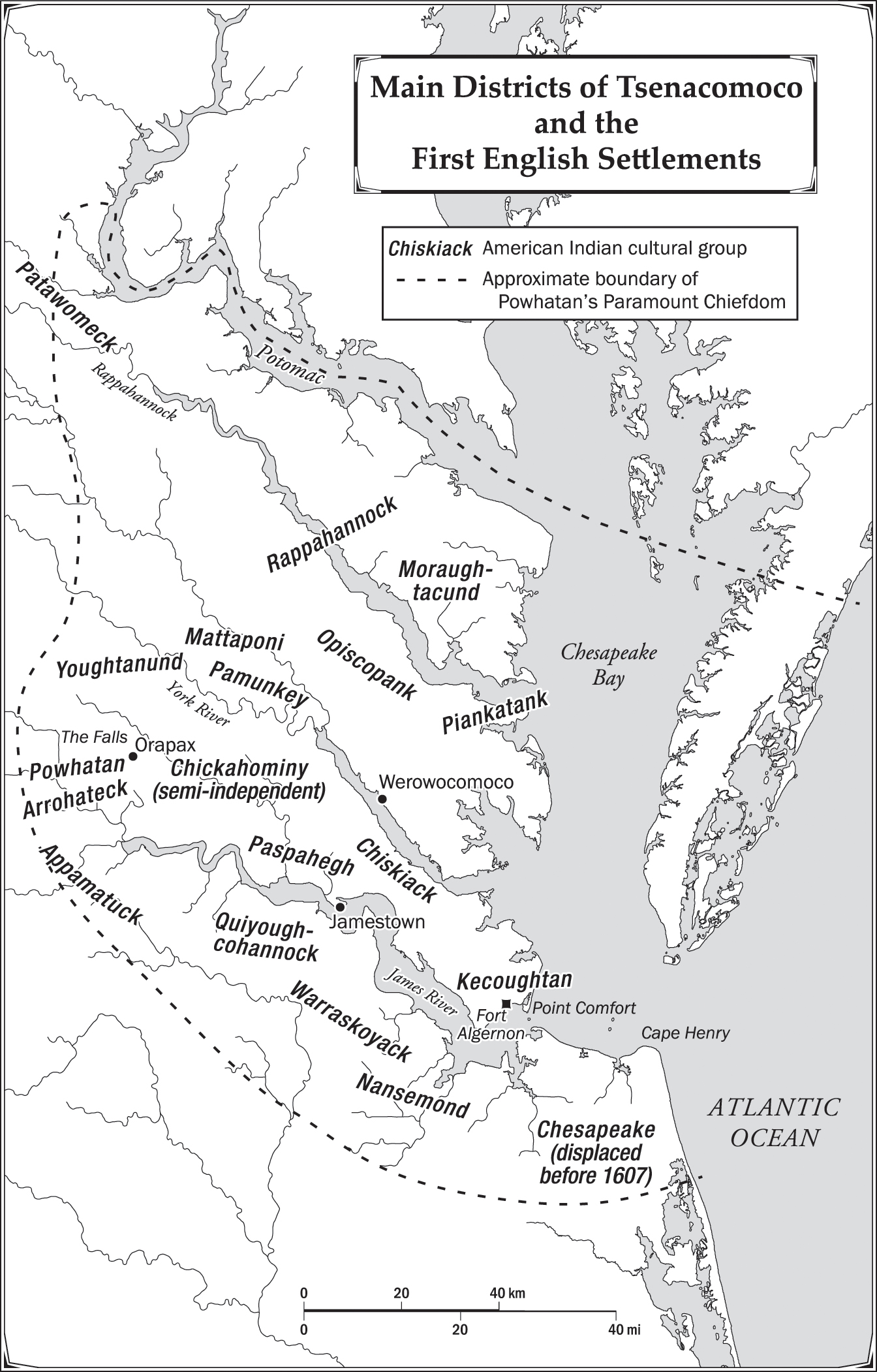

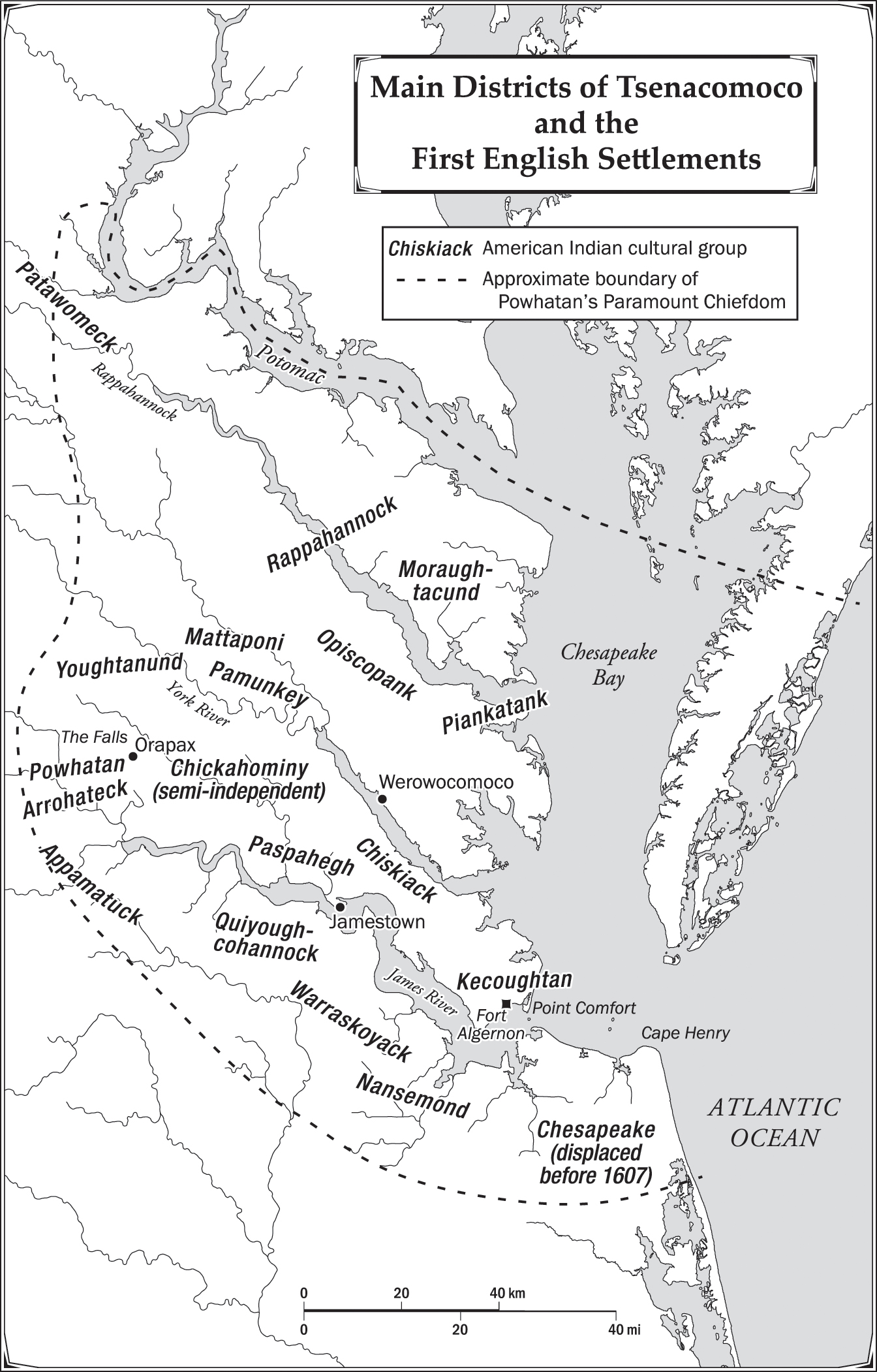

More than a year earlier, on the fifteenth of May, 1609, the Sea Venture set sail from London, the admiral of an impressive fleet. The Diamond , the Falcon , the Blessing , the Lion , and the Unity , as well as a pinnace (a shallow-draft boat designed for coastal exploration) too small to be named, sailed behind her, headed to Virginia, the third and by far largest resupply of two-year-old, fledgling Jamestown, Englands tiny, rough-hewn, and hungry little campsite, its only toehold on the vast American continent. The flotilla was the largest and most expensive and most promising overseas expedition that England had ever organized, and the six hundred people crowded into the vessels would triple or quadruple the population of the colony. It seemed that all England applauded their departure. Crowds of Londons ever-curious spectators, one historian explains, lined the rivers banks and cheered as the seven ships, sails billowing, flags flying, glided past them on the spring afternoon. Several weeks later, after a stop at Plymouth increased the fleet to nine vessels, they left Englands toe, the very westernmost tip of the nation, following the setting sun into the newly charted seas of the vast North Atlantic. Seen from the lands end, they disappeared into oblivion, as if a curtain shut upon them. No one in England would hear from the fleet for ages. No one expected to. Ships that sailed west into the Atlantic reappeared, if they ever did, almost miraculously, many months or even years later.

This time the Atlantic was quiet. Each morning from the second of June to July twenty-third, 1609, the sun rose in a clear sky off the stern, and it chased the squadron all morning long, till in the afternoon and evening the ships chased the setting sun toward Virginia. The seas were calm. It was a relief to Sir George Somers, admiral of the fleet, who did not know what to expect. Previous English expeditions followed the winds south, island-hopping to the Canaries, then the West Indies, and thence to Jamestown. But the Virginia Company had recently scouted a quicker, more direct line, a northern passage that avoided the Caribbeans hazard of Spanish ships, and Somers followed this unfamiliar route. The month and a half of fair breezes and clear skies seemed to justify the gamble. They made such good time that one of the pinnaces could not keep up. The flagship, the Sea Venture , had to tow it across the Atlantic.