The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

CONTENTS

To my wife, Lynne

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

My deepest thanks go:

To James Fitzgerald, my agent, who took me on when I needed guidance and help. To Michael Flamini at St. Martins Press, who was ready with encouragement and guidance; I hope I have lived up to his expectations.

To the people of Bermuda for making me feel welcome during my brief sojourn to do research. To William Kelso and his staff on the Jamestown Rediscovery Team for their hard work and dedication in bringing Jamestown back to life. To my friends and family in Richmond, Virginia, for hospitality and support.

To Mark Ford, mentor and loyal friend for many years, for all his support. To Sylvia Andrews and Peter Hawkins and the other members of my writing circle for critiques of the work in progress. To Jack Nordloh for his words of encouragement. To Jack Furet for all his help over the years. To John and Vicky Manley for their assistance in solving a particularly vexing problem.

Special thanks to that overlooked group of professionals, the librarians, who give unstintingly of their time to help writers like me find the materials we need. And to my mother, Mary Doherty, herself a librarian, for instilling in me a love of books and history.

Very special thanks to my wife, Lynne, for taking the time to lend her editing skills to the effort, for listening to my talk about the Sea Venture and her passengers, and, of course, for all her loving pep talks in the dark days.

Any mistakes in this volume are mine and mine alone.

Preparations Most Urgent

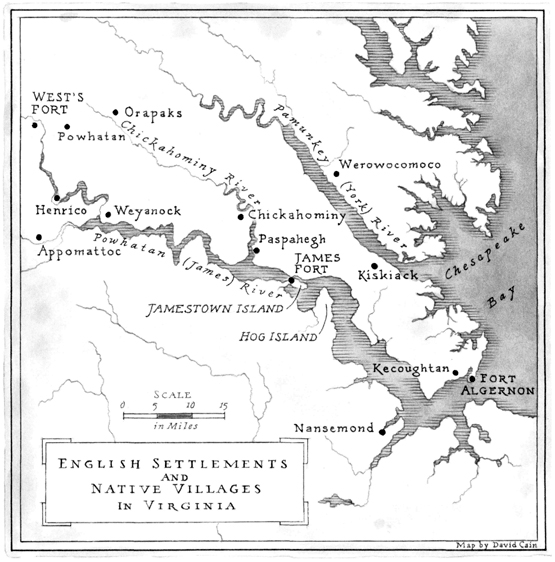

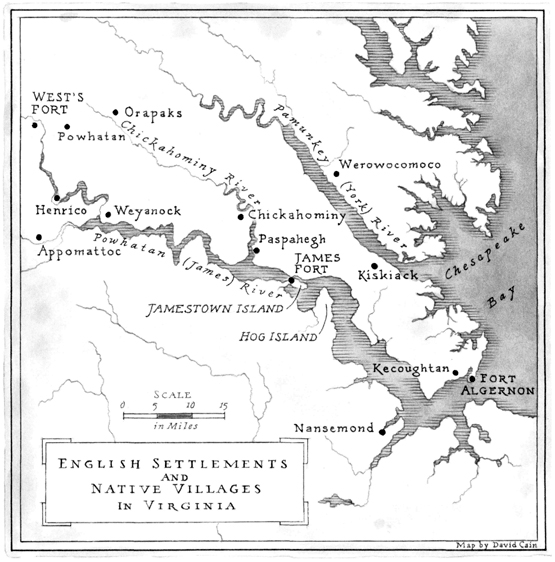

In the spring of 1609, all London was filled with talk of Virginia. Businessmen who gathered in the nave of old St. Pauls and in the vast courtyard of the Royal Exchange spoke excitedly of the profits that might be theirs if they invested in a new scheme to settle the rich lands named in honor of the Virgin Queen. Sailors on the docks and boatmen on the Thames traded in wild tales of the riches that waited in the lands of the Chesapeake. Gentlemen and poets who met in the Mermaid Tavern and other London watering holes mused late into the night, night after night, of Virginia, nothing but Virginia. Preachers spoke of the chance to do Gods work while finding opportunity in that far-off country the Almighty had set aside for England. The unemployed and desperate, whose minds raced at the thought of owning their own land, made hurried plans to leave crowded, dirty, smoky London for a better life, no matter what the dangers.

Profits, freedom from want, and the possibility of escape from desperate lives, all these things and more seemed possible in this place called Virginia. Though most who dreamed of emigrating knew as little of the distant lands across the Atlantic as they knew of the moon, they were willing to believe the lines that had been written by the poet Michael Drayton, giving voice to the hopes and dreams of the first Virginia settlers who had left England for the New World in late 1606:

Virginia,

Earths only paradise!

Where nature has in store

Fowl, venison, and fish,

And the fruitfulst soil

Without your toil,

Three harvests more,

All greater than your wish.

It mattered little to these westward-looking Englishmen that many of those who had already made the journey from England to the lands they called Virginia found death instead of opportunity. It mattered little that in the two years since a group of English settlers struggled ashore in Virginia to establish a settlement they called Jamestown no fortunes had been made, no gold or pearls or silver had been discovered. This was a new day, a new opportunity for all to gamble their money (or their very lives) in the hopes that England would finally, after a long history of failure, establish a profitable, secure, and lasting presence in that far-off land most could not even begin to imagine, a settlement where dreams could come true.

One Londoner who saw Virginia as a place he might find financial salvation was William Strachey, a failed civil servant, poetaster, and sometime playwright. The son of a successful gentleman with landholdings in rural Essex, Strachey had studied law at Grays Inn, but cut his training short to spend his time scratching out mostly unpublished verse and socializing with Londons literary set. He was close enough to Ben Jonson, the poet and playwright, to write a dedicatory verse included in the quarto version of Jonsons play Sejanus, performed by Shakespeares company in 1603 and published in 1605. Stracheys circle of friends almost certainly also included George Chapman, a collaborator with Jonson in the writing of Eastward Ho!, a somewhat scandalous play about the Virginia colony.

Living a literary gentleman-poets lifestyle took so much of Stracheys time in the early 1600s that he seems not to have had many hours to devote to the business of making money. And what with evenings at the theater and afternoons spent in Southwark watching cockfights and bearbaitings and hours spent drinking and swapping lies with his friends, Strachey found himself forced to borrow heavily from Londons moneylenders. In 1606, in an attempt to claw his way free from the morass of debt in which he found himself, he used family connections to land a job as secretary to the ambassador to Constantinople and traveled with his employer to the Turkish capital. His hopes of recouping his fortunes in the foreign service ended in near disgrace and even deeper indebtedness, however, when he had a falling out with the ambassador and was forced to borrow money to return to London.

By the spring of 1609, Stracheyhe was aged thirty-six or thirty-seven by thenwas so deep in debt that he feared imprisonment. Sometime that spring, a friend who had been jailed as a debtor wrote a letter to Strachey pleading with him for aid. Strachey replied that he was haretly sorrie he was unable to help, adding that he was himself in danger of being sent to prison for want of present money. In fact, Stracheys situation was perilous. As the weather warmed that spring and the Thames thawed and began flowing again after one of the coldest winters ever, he knew that each time he dared to quit his lodgings for even a brief foray into the street, he ran the risk of an unpleasant scene with a creditor orworsearrest and a stint in the Clink or one of Londons other infamous gaols.

Still, it is safe to assume that Strachey managed to sneak from his lodgings to meet with friends, probably to try to borrow funds or simply to escape the tedium of his rented rooms. It would be surprising if he did not, on occasion, make his way along Cheapside, Londons main market street, to the turning that led to the door of the Mermaid Tavern, where his friends Jonson and Donne were frequent visitors. Perhaps it was there that Jonson told himit was advice he gave to othersthat the only hope for any man in debt was to flee to Constantinople, Ireland, or Virginia if he wanted to rebuild his life and repair his credit. Strachey had already tried his luck in Turkey, and failed. Now, while Ireland may have beckoned, it must have seemed to the impoverished poet that Virginia offered a better chance to escape his creditors and perhaps, just perhaps, his best opportunity, if not for riches, then for security and freedom.