In 1580, a twenty-seven-year-old English clergyman set off on horseback to see a seaman. The rider, Richard Hakluyt, who had recently received his Master of Arts degree from Oxford University, journeyed 200 miles over muddy, rutted roads to meet Thomas Butts, who had sailed on one of the first English expeditions to Newfoundland. Hakluyt was eager for information on the exploits of English explorers and travelers.

This curiosity had been roused by an older cousin, also named Richard Hakluyt, a lawyer by training, who became one of the first English experts in geography. Merchants and trading companies drew on his expertise and knowledge before launching business ventures in many parts of the world, and they paid him handsomely for his advice.

England had lagged behind in the great Age of Discovery that spanned the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It had taken no part in the early forays that had enriched the cities of Italy and led to the founding of the Portuguese and Spanish empires. The merchandise that England exported and imported was carried in foreign vessels, and its small merchant fleet had been built largely in foreign shipyards. Even when Englishmen led their own expeditions, their navigators usually came from other countries.

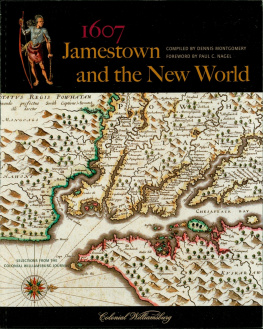

John Cabot, an Italian navigator and explorer sailing under the British flag in 1497, first established Englands claim to land in North America. A commission by King Henry VII gave Cabot free authority, faculty and power to sail to all parts, regions and coasts of the eastern, western and northern sea, under our banners, flags and ensigns, with five ships or vessels of whatsoever burden and quality they may be, and with so many and with such manners and men as they may wish to take with them in the said ships, at their own proper costs and charges, to find, discover and investigate whatsoever islands, countries, regions or provinces of heathens and infidels, in whatsoever part of the world placed, which before this time were unknown to all Christians.

Cabots expeditions made landfall on parts of the North American coast possibly Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Maine untouched by Europeans since the Viking voyages centuries before.

In 1508, Cabots son, Sebastion, traced his fathers path across the Atlantic in search of a northwest passage through North America that would provide access to the riches of the Orient. Seventeen years later, Sebastian Cabot sailing for Henry VIII, the second monarch of the Tudor dynasty endeavored to repeat Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellans circumnavigation of the globe. Sebastian abandoned the effort in pursuit of riches in Brazil, but his explorations informed another role he played for his country that of cartographer.

Maps that Sebastian made outlined the continents of Europe and Africa, but as late as 1542, North America was depicted as little more than a large reef blocking passage to the Orient.

Richard Hakluyt, who would play a large part in stoking the English passion for adventure and discovery, studied the voyages of John and Sebastian Cabot. When visiting his older cousin, his guardian since the death of his father in 1557, he recalled: I found lying open... certain books on cosmography, with a universal map; [my cousin] seeing me somewhat curious in the view thereof, began to instruct my ignorance... he pointed out all the known seas, gulfs, bays, straits, capes, rivers... and the territories of each part, with declaration of their special commodities and particular wants.

Hakluyt studied for the ministry at Oxford, a profession that would provide him an income while he continued his geographical research. He also worked to master a number of languages because few texts on geography were written in English at the time.

In addition to his research, Hakluyt collected practical information from merchants, mariners like Thomas Butts, travelers, and from reports gathered by trading companies agents in foreign countries. He studied the newest maps and globes and corresponded with leading geographers - men such as Geradus Mercator and Abraham Ortelius.

In 1582, Hakluyt published his first book, Divers Voyages Touching the Discovery of America. His aim was to awaken his countrymens interest in exploration and colonization. He spoke to middle-class merchants, stressing the importance of American colonies to trade, pointing out that such colonies would provide work for the unemployed and listing certain commodities growing in part of America that were needed in England. In Divers Voyages, he also included maps and the information he had painstakingly gathered from the merchants and mariners of England.

The book created widespread interest. Hakluyts work was recognized with an official appointment as chaplain to Sir Edward Stafford, the English ambassador at the French court in Paris. Hakluyt took advantage of his new position to collect accounts of French and Spanish expeditions to the New World and gather further information that might be useful to English explorers in America. He sought out exiled Portuguese captains and pilots and became friendly with French and Italian sailors, who showed him animal skins painted by Indians and a piece of a sassafras tree from Florida that was said to have medicinal qualities.

In 1584, Sir Walter Raleigh recalled Hakluyt from France to help persuade Queen Elizabeth I to establish a colony in America. Hakluyt wrote a report that he presented to the queen. Known briefly as The Discourse on the Western Planting, his report was aimed at proving to the frugal monarch that Raleighs colonies could show a profit and increase Englands power and prestige.

Without colonies, he argued, England could not match the power of Spain and Portugal. English privateers and warships needed bases from which they could strike Spanish and Portuguese treasure ships and fishing fleets. And in challenging the might of the Catholic empires, England would bring glory not only to itself as a nation, but to the Protestant cause that it led. But there were more practical reasons to consider. England needed new markets for its goods and new sources of raw materials. Such aims only could be accomplished by setting up farms and colonies on the other side of the Atlantic.

Hakluyt listed the types of emigrants most needed in the New World: carpenters and craftsmen for building, gardeners to establish vineyards and orchards, and soldiers for defense. Valiant youths rusting and hurtful by lack of employment could be sent overseas. Anglican clergymen could preach the gospel to the natives, he argued, bringing salvation to untold thousands.

Hakluyt later popularized his cause by publishing The Principal Navigations, Voyages, and Discoveries of the English Nation, a collection of travelers accounts. This work, more than any other, helped direct the English peoples increasing interest in exploration and foreign trade.

Though Hakluyt longed to cross the Atlantic, he would never make the journey. While he publicized the western plantation of colonies, others had taken steps toward expanding the English empire overseas. The first attempt to colonize the New World was led by Sir Humphrey Gilbert, the half-brother of Walter Raleigh. Gilbert enjoyed a reputation for courage and energy. In 1566, he had petitioned Elizabeth to discover a passage by the north to go to Cataia [Cathay].

Finding this passage by the north would preoccupy expeditions for centuries to come. But Gilberts appeal went unanswered, and in 1573, he devoted himself to writing Discourse of a Discovery for a New Passage to Cataia. In it, he claimed that America was the lost island of Atlantis. And, he argued, since there was a passage to the south (the Strait of Magellan), there must be a passage to the north, which, he wrote, I now take in hand to discover.