Also by Peter Firstbrook

The Obamas: The Untold Story of an African Family

Surviving the Iron Age

Lost on Everest: The Search for Mallory & Irvine

The Voyage of the Matthew: John Cabot and the Discovery of North America

A Oneworld Book

First published by Oneworld Publications 2014

This eBook edition published by Oneworld Publications 2014

Copyright Peter Firstbrook 2014

The moral right of Peter Firstbrook to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-85168-950-7

Ebook ISBN 978-1-78074-107-9

Jacket design by Holly McDonald

Typesetting and eBook design by Tetragon, London

Map artwork copyright Peter Firstbrook

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3SR, England

Authors Note

Nobody who writes about John Smith could do so without acknowledging two biographers from the past. Bradford Smith, together with his Hungarian colleague, the historian Laura Striker, published John Smith: His Life & Legend in 1953. Philip Barbour dedicated much of his later life to writing about Smith, including The Three Worlds of Captain Smith (1964) and many papers. Barbours three-volume set, The Complete Works of Captain John Smith (1986), represents a lifetimes passion for the subject, and was published six years after his death.

For simplicity, all quotes from John Smiths writings have been taken from The Complete Works . Reading original Jacobean writing in its original form is demanding, so Barbours typographic changes to Smiths original writings remain here. These include altering u to v where appropriate, and v to u where needed. The archaic vv has been changed to the modern w, and I have used the modern s to replace . The many italicized words in the first editions have been set in roman.

Quotations from other individuals have been taken from Barbours two-volume set, The Jamestown Voyages 16061609 (1969), and from Edward Wright Hailes Jamestown Narratives: Eyewitness Accounts of the Virginia Colony (1998). The references make these selections clear.

Dates during this period can cause confusion. By the 1600s, the Julian calendar had drifted by ten days from the solar calendar, so some European countries had already adopted the more accurate Gregorian calendar. Italy, France, Portugal and Spain approved this new calendar in 1582, but England retained the Julian calendar until 1750. This biography is predominately about English history, so the old-style Julian calendar has been retained for English dates. Spanish, Italian and eastern European dates have been retained in the new style Gregorian calendar, and are indicted (NS).

However, the calendar is more complicated than this. During the period in question, the New Year also varied. Throughout this book, the modern day for New Year on January 1 is used, rather than the old-style New Year, which began in March. In the old-style, John Smiths baptism day was January 9, 1579, and appears in some modern sources as January 9, 1579/80; here I have used the simpler form, January 9, 1580.

The name of Virginias first settlement is variously called James Fort, James Towne, Jamestowne and James Cittie in the literature. For consistency, Jamestown has been used throughout. Foreign words are shown in italics.

The correct terminology used to describe the indigenous peoples of the Americas is a topic of ongoing debate. When the English colonists arrived, the region was settled by a confederation of tribes led by a mamanatowick , or paramount chief, called Wahunsenacawh. He was known more commonly by the English as Powhatan, after the name of the village where he was most likely born. Each tribe within the Powhatan empire had its own name, and whenever possible I have referred to these peoples by their tribal affiliation. Collectively they are known as Algonquian-speaking peoples, Tidewater people, or most simply the Powhatan.

The term Indian results from an historic error made by the Europeans, and where possible I have tried to avoid perpetuating this terminology. Likewise, I have preferred to use the name Wahunsenacawh rather than Powhatan or Chief Powhatan. However, for historical reasons these words do creep into the text occasionally, particularly when referring to the contemporary English or European view of their neighbours (and of course they also appear in the colonists quotes). When used, no disrespect is intended.

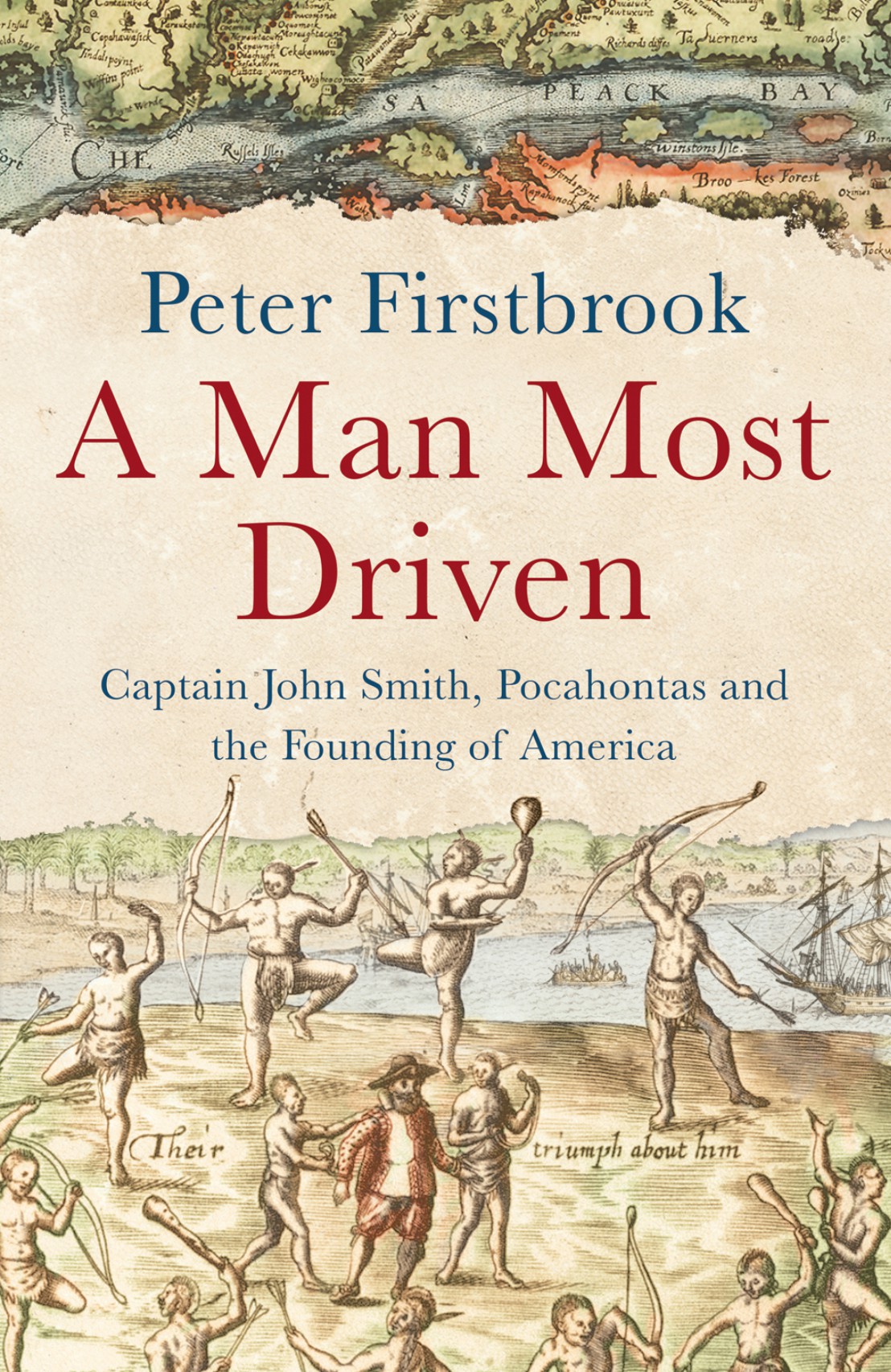

A Man Most Driven

Prologue

Yet God made Pocahontas the Kings daughter the meanes to deliver me: and thereby taught me to know their trecheries to preserve the rest

John Smith, New England Trials (1622)

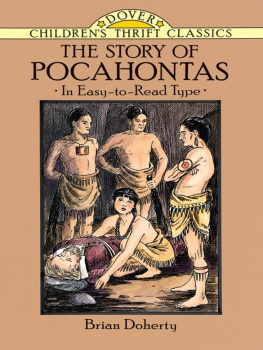

An apocryphal tale? John Smith Saved by Pocahontas, painted by Alonzo Chappel, circa 1865

On December 30, 1607, an Englishman was dragged before the paramount chief of the native Powhatan tribes of Virginia. His abductors brought out two large rocks, and placed him with his head resting on the boulders. He lay prostrate, waiting for a mercifully swift execution. It was dark inside the longhouse, and as the prisoners eyes adjusted slowly to the gloom he became aware that, around him, about two hundred people were looking on in fascination. For most, it was their first sight of a European.

The prisoner was strong but not tall, standing only as high as his guards shoulders. His thick beard mainly covered the ruddy complexion of someone who had spent most of his life in the open. The man was a few days short of his twenty-eighth birthday, an anniversary he did not expect to celebrate. As he lay on the ground, the guards raised their war clubs above his head, waiting for the command from their chief to execute the prisoner in their traditional manner by beating the brains out of his skull.

From the shadows of the smoke-filled longhouse, a young girl of perhaps ten or twelve emerged, naked from the waist up, and with only a wisp of black hair hanging down from the back of her shaved head. She turned to the great man presiding over the ceremony, with a familiarity and self-confidence that suggested she knew the chief well. She did, for he was her father. The girl pleaded for the strangers life to be spared. The Englishman understood little about what was being said, for his comprehension of the Algonquian language was still rudimentary.

The chief considered his daughters appeal carefully. He was an old man, perhaps sixty or seventy years, broad-shouldered, fit and powerfully built for his age. He wore a robe of raccoon skins with the tails still attached, and around his neck a chain of pearls. He was clearly held in awe by all those present, and at the least frowne of his brow, their greatest will tremble with feare.