Table of Contents

For Sally, Ben, and Lizzie

with love

Reveal to us the courts of China and the unknown straits which still lie hid: throw back the portals which have been closed since the worlds beginning at the dawn of time. There yet remain for you new lands, ample realms, unknown peoples; they wait yet, I say, to be discovered.

Richard Hakluyt, the younger 1587

After good deliberation, hee [Wahunsonacock] began to describe mee the Countreys beyonde the Falles, with many of the rest... Nations upon the toppe of the heade of the Bay... the Southerly Countries also... [and] a countrie called Anone, where they have an abundance of Brasse, and houses walled as ours. I requited his discourse, seeing what pride hee had in his great and spacious Dominions, seeing that all hee knewe were under his Territories.

Captain John Smith, 1608

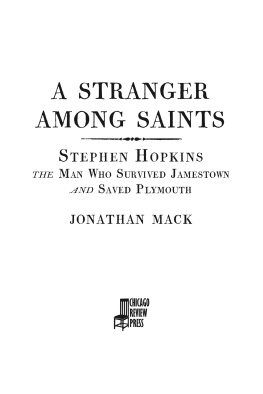

Acknowledgments

I should like to thank all the friends and colleagues who have helped me with this book over the years. Early versions of the argument were presented at the University of Sussex, the Henry E. Huntington Library, and Jamestown, and I am grateful for comments by participants. Thanks to Warren M. Billings, Karen Kupperman, Timothy Breen, Alan Taylor, Peter Onuf, and Martha McCartney, among others, for many stimulating discussions. I have also benefited enormously from conversations with William M. Kelso and Beverly Straube of the Jamestown Rediscovery project, who have generously shared their expert knowledge. Thanks to all those colleagues on several 2007 committees (on which I have the privilege to serve) for stimulating my thinking about why Jamestown matters.

At the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, I am most grateful to Colin Campbell and Cary Carson for their support and encouragement. Thanks to my colleagues at the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library for all the many ways they have helped, especially Inge Flester, Gail Greve, George Yetter, and Don Stueland. I should like to thank also the staffs of the British Library, the Alderman Library at the University of Virginia, and the Swem Library at the College of William and Mary. I am grateful to Marianne Martin for providing expert help tracking down illustrations, and to Rebecca L. Wrenn, of the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, for drawing the maps.

Don Lamm provided excellent advice at an early stage of the manuscript and helped me sharpen the writing. Lara Heimert, Executive Editor at Basic Books, has done a wonderful job of editing. I am especially grateful for her tireless efforts to encourage me to shorten unwieldy paragraphs and sentences (those that remain are wholly my responsibility). I am grateful also to David Shoemaker, Kay Mariea, Jennifer Blakebrough-Raeburn, and other staff at Basic who have brought the book to completion.

I cannot adequately express my gratitude to my family for their patience during the long process of research and writing, and particularly the last few months when all too often I disappeared into my study. The book is dedicated to them: my wife, Sally, and Ben and Lizzie, with all my love.

Prologue

Before Jamestown

LONG BEFORE JAMESTOWN, in the summer of 1561, a Spanish caravel buffeted by storms somewhere off the coast of present day South Carolina was driven several hundred miles to the north. As the winds dropped and the rain cleared, the crew saw an immense bay; so wide that had it not been for a faint trace of land on the horizon they might have been forgiven for thinking they had been blown back out to sea.

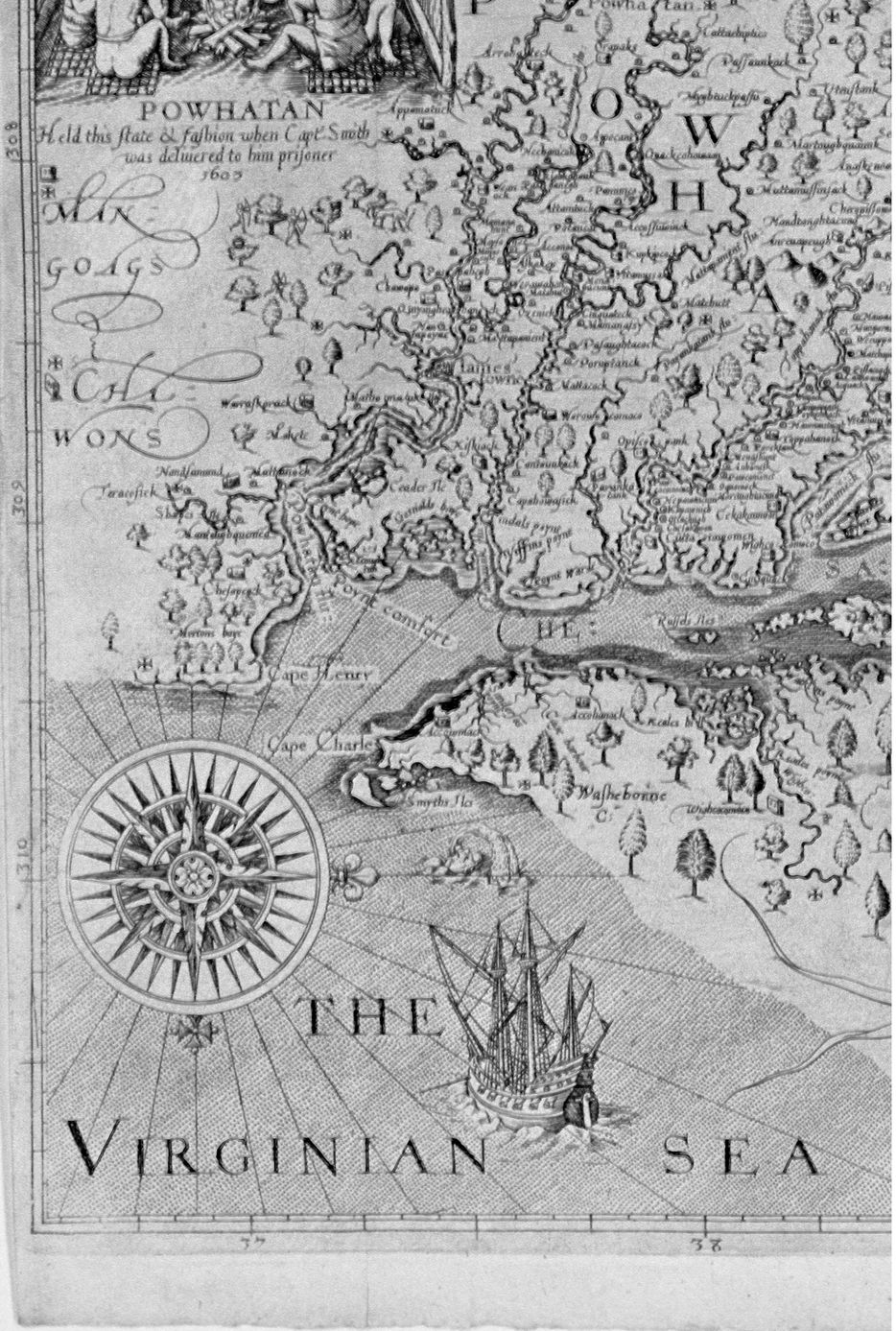

Crossing the bays gray-green waters to the southern shore, the ship proceeded cautiously inland, where the Spaniards found many fine harbors, fertile meadows, fresh running springs, and everywhere an abundance of treespines, hickories, oaks, cedars, cypresses, poplars, black walnuts, and maplesgrowing in wild profusion to the waters edge. They anchored in a large river, possibly the Chickahominy, to replenish supplies and make repairs and there encountered a small group of Indians, two of whom (a principal person among them and his servant) agreed to accompany them on their voyage. Whether the ships commander, Antonio Velazquez, realized that he had found the Bahia Santa Maria (Chesapeake Bay), first sighted by Pedro de Quejo thirty-six years earlier, he knew he had made an important discovery. With the two Indians on board, he decided to return to Spain.

Reaching Lagos, Portugal, in late August, Velazquez left his ship and traveled overland to Seville to sort out some business affairs. He then made his way some three hundred miles to Madrid to report his voyage and present the young Indian, Paquiquineo (named Don Lus de Velasco in honor of the viceroy of Mexico), to the king, Philip II. On the journey, he and Don Lus took the road through the beautiful river valley of the Guadalquivir, a checkerboard of wheat fields, vineyards, olive groves, and citrus orchards, to the Moorish city of Crdoba with its great mosque, before turning north into the high, austere tableland of the Mesta, given over to vast sheep walks and scattered rural industries. Arriving in Madrid, little more than a large village when Philip II established his court there earlier in the year, they would have found a bustling town packed with courtiers, royal officials and their staffs, high-ranking churchmen, retailers, and merchants, all having flocked to the new capital of Spain.

Exactly when Don Lus was presented to the king is unknown. To those who witnessed it, however, the meeting must have appeared a study in stark contrasts: on the one hand Don Lus, an indio from a remote part of the North American littoral, who knew nothing of European civilization or Christianity; and on the other Philip IIruler of an empire embracing the Americas and large parts of western Europe, the greatest the world had ever seenbelieved by his subjects to be Gods shepherd on Earth and herald of a universal Catholic monarchy that would reunite Christendom and eventually all peoples under one monarch, one empire, and one sword. Perhaps because of the kings curiosity about the Indians land and the possibility of converting the people there to Catholicism, or perhaps because he was intrigued by the Indians evident intelligence, Don Lus soon became one of Philips favorites.

At first, Don Lus may have enjoyed the life at court and in Madrid, but during the winter his thoughts turned homeward; after speaking of his desire to return to his own land, the king granted him permission to go back in the spring. Arrangements were made for Don Lus, accompanied by Valezquez, to travel first to New Spain (Mexico), and then the Indian and a small group of Dominican missionaries would continue on to the Bahia Santa Maria. Accordingly, Don Lus joined the convoy that sailed from Cdiz at the end of May and arrived at San Juan de Ulua, roadstead of Vera Cruz on the Gulf Coast of Mexico, ten weeks later.

Don Lus together with several companions first went to Mexico City to meet the viceroy, Velasco, who wished to oversee the mission to the Indians homeland. Forty years after the collapse of the Aztec Empire, most of the old city of Tenochtitln had been demolished and replaced with a great public square around which were located the new citys principal buildings, constructed in Spanish baroque style out of the stone and rubble of Aztec pyramids and temples. The Indian had little opportunity to acquaint himself the city, however. Shortly after arriving, he became seriously ill (possibly smallpox or dysentery) and was thought lost. Gradually nursed back to health at a Dominican convent, he and his servant were baptized and chose to remain with the friars to learn the Catholic faith and Spanish ways.