As always in a project such as this, there are many people behind the scenes who have helped in a number of important ways. As such, I wish to acknowledge those who have provided their time, expertise, guidance, and assistance in helping me finish this book.

Initially, I would like to thank Ted Zuber for his continuing friendship and outstanding artwork, as well as Chris Johnson for his detailed map work. I would also be remiss if I did not thank Suzanne Surgeson for her assistance in accessing Parks Canada graphics, and Denise Kerr for her expert editorial support. I must also thank Paramount Press, as well as Robert Flacke Sr., and the Fort William Henry Corporation, who made possible the use of a number of the graphics that are used in the book. In addition, I must also highlight the incredible work of the Dundurn editorial and design team, specifically the project editor, Michael Carroll, and editor Cheryl Hawley, who turned a raw manuscript into the polished product that you hold in your hands. Finally, as always, I wish to thank Kim for her continuing tolerance and patience of my never-ending projects and historical pursuits.

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 1

ADAPT OR DIE

The French Canadians and their allied Natives hadnt always controlled the wilderness of North America. The French Canadians skill at scouting, raiding, and ambushing in other words, guerrilla warfare was learned by necessity. Starting in the early 1600s, and for almost 100 years, they were the targets of Native, mostly Iroquois, raids. For a century the French Canadians suffered war. Eventually, they learned to make war. They came to understand that aggressive offensive action was the best defence for the growing French colony.

From the beginning, the survival of the colonists of New France depended on ingenuity and adaptability. The harsh reality and circumstances of the New World dictated a realistic approach to life in the new French colony. First, New France was a distant wilderness colony in an overtly hostile land. This severely limited its population base, since the constant threat from the Iroquois, and later the English, made it difficult to recruit colonists. For those adventurous enough to venture to the New World, their journey was often marred by hardship and death. Making the situation worse was the fact that New France was not a priority for the French motherland. France was willing to spend only so much to ensure the colonys development and security. France wanted to extract wealth from the New World, not spend money on it. This meant that New France would live or die by its ability to protect itself.

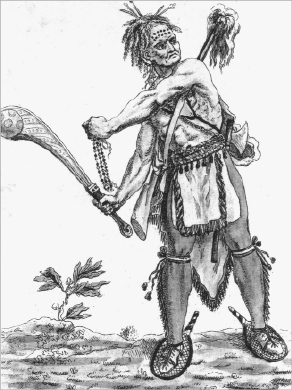

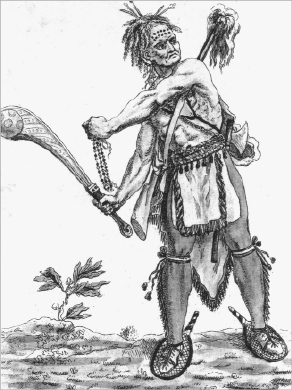

An Iroquois warrior, the scourge of New France.

LAC, C-3165.

KEY FACTS

Iroquois

The Iroquois, an indigenous people of North America, are commonly known as the people of the longhouse. During the 1500s a number of Iroquois tribes came together to form a confederacy (the Five Nations), which consisted of the Cayuga, Oneida, Onondaga, Mohawk, and Seneca tribes. The Tuscarora joined the confederacy (making it the Six Nations) in approximately 1715. The Iroquois were a warlike people whose agricultural base (they grew mostly corn, beans, and squash) allowed them to support a large population as well as expeditionary raids. The Huron viewed the Iroquois as devil men, who needed nothing, and were hard to kill.

During the French and Indian War, the Iroquois allied themselves with the British against their traditional enemies, the French and their Algonquian allies, although few warriors actually participated with the British on campaigns. During the American Revolution the Iroquois once again sided with the British. After a successful campaign against frontier settlements in 1779, General George Washington ordered a massive offensive against the Iroquois nations to destroy them. When the war ended, a group of Mohawks left New York to settle in Canada. For their service to the Crown they were given a large land grant on the Grand River near present-day Brantford, Ontario. The Iroquois fought once again with the British during the War of 1812.

As a result, the inhabitants and leaders of New France developed a way of war that reflected their environment, their capability, and their temperament. They could not afford to fight for extended periods of time or suffer many casualties, since their population was so small. They had to learn how to fight and survive in the wilderness of North America.

SHOCKING REALITY

A Shortage of Colonists

Initially, very few settlers ventured to the New World. By the middle of the 17th century there were only approximately 2,500 people in New France. Many of them were explorers, fur traders, and missionaries. But the lure of freedom, opportunity, and especially wealth was enough of a draw to generate growth and the French established settlements and a series of forts, mostly for fur trading.

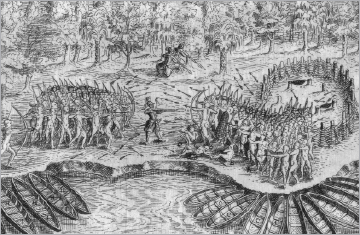

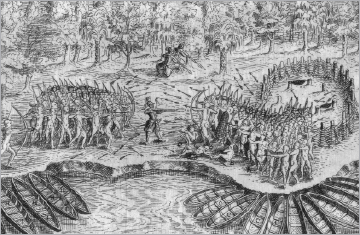

Samuel de Champlain, the governor of New France, and his Native allies defeated an Iroquois war party near the present town of Ticonderoga, New York, on July 30, 1609.

LAC, C- 6643.

Simply put, it was a matter of adapt or die. Compared to Europe, the Canadian climate was harsh. The thick, deep forests seemed impossible to penetrate and the Natives, especially the Iroquois, were hostile. The French colonists had to make alliances. For this reason, Samuel de Champlain, the first governor of New France, quickly entered into treaties of friendship and trading partnerships with a number of northern tribes such as the Abenaki, Algonquin, Huron, Montagnais, and Outaouais. Champlain did this even though he knew that many of these tribes were locked in conflict with the far more aggressive Iroquois confederacy. His decision had serious consequences and eventually made war inescapable.

KEY FACTS

Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain was a French navigator, cartographer, draughtsman, soldier, explorer, geographer, diplomat, and writer. He is known as the Father of New France.

Champlain was born into a family of master mariners and began exploring North America in 1603 under the tutelage of Franois Grav Du Pont, a navigator and merchant. Champlain was part of the expedition that explored and settled Acadia from 160407. The following year, in July 1608, he founded Quebec City. In his determination to protect French settlements in New France, he entered into a series of alliances with local tribes that brought France into conflict with the Iroquois, which led to almost a century of fighting.

He was captured by the English in 1629, after a siege of Quebec City, but returned to New France in 1633 as the governor. His great success in establishing a fur trading organization that was economically viable laid the foundations of New Frances development. Champlain suffered a severe stroke in October 1635, and passed two months later. He was buried in Quebec City, although the exact site is not known.

However, the attack was a great success. On July 30, 1609, Champlain led a combined French, Algonquin, and Huron force, the first of its kind, against the Iroquois at a site near present-day Ticonderoga, New York. Armed with an arquebus (an early type of musket), with his first shot Champlain killed two Iroquois chiefs and injured a third warrior. His two French companions, also equipped with firearms, opened fire from the flank. This caused the Iroquois to panic, particularly because of the weapons theyd not yet encountered, and they fled. The following year, Champlain and his allies also drove an Iroquois war party out of the Richelieu Valley.