F OR THE CONVENIENCE OF THE READER, I HAVE ALTERED THE spelling and punctuation of historical passages to make them conform to modern conventions but have retained original capitalization to offer an impression of the original sources. No substantive changes of any sort have been made to direct quotations.

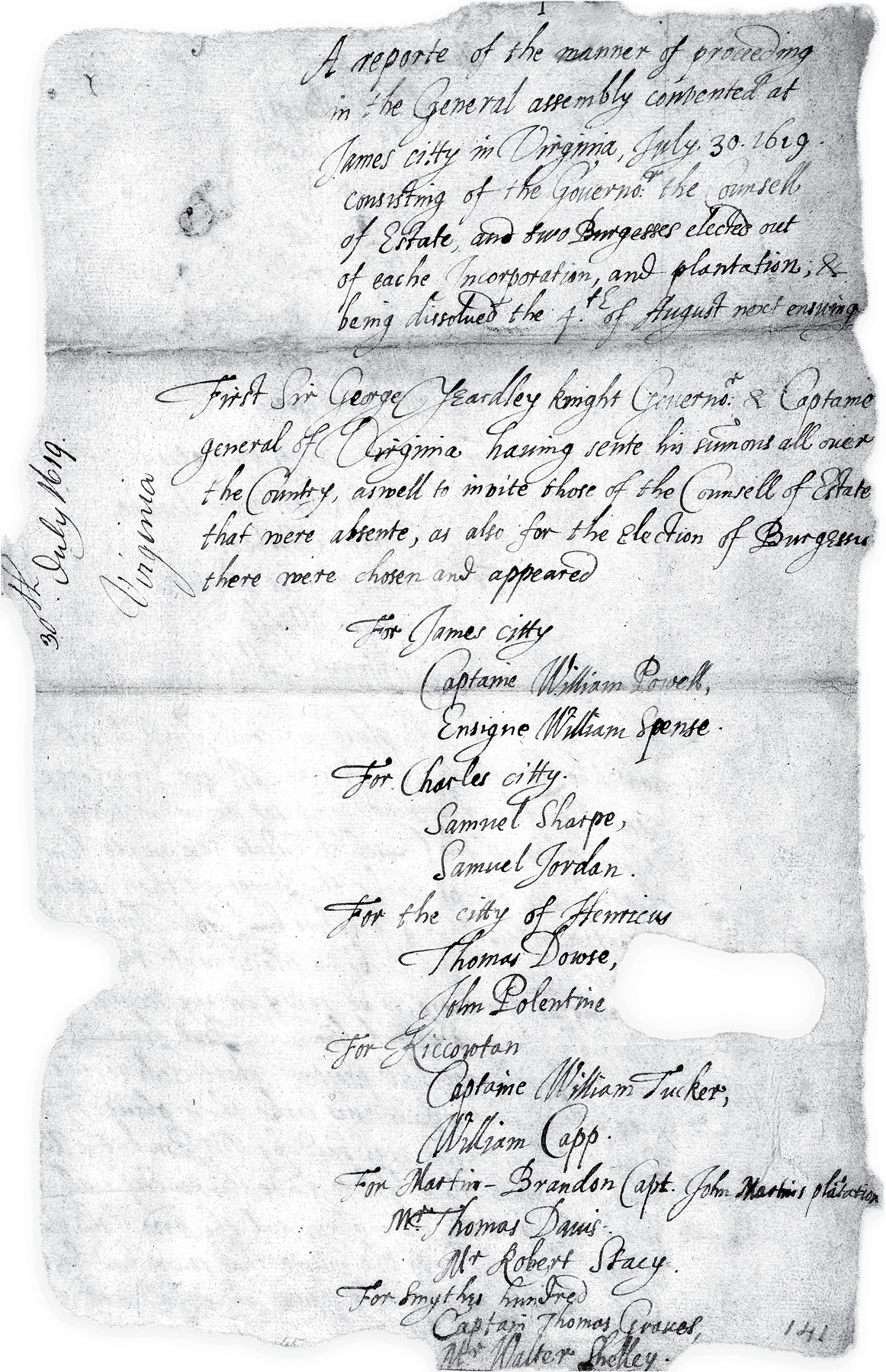

A LONG THE BANKS OF THE J AMES R IVER, V IRGINIA, during an oppressively hot spell in the middle of summer 1619, two events occurred within a few weeks of each other that would profoundly shape the course of history. Convened with little fanfare or formality, the first gathering of a representative governing body anywhere in the Americas, the General Assembly, met from July 30 to August 4 in the choir of the newly built church at Jamestown. Following instructions from the Virginia Company of London, the colonys financial backers, the meetings principal purpose was to introduce just Laws for the happy guiding and governing of the people. The assembly sat as a single body and was made up of the governor, Sir George Yeardley, his four councilors, and twenty-two burgesses chosen by the free, white, male inhabitants of every town, corporation, and large plantation throughout the colony.

No one in Virginia in 1619 or in the years following could have possibly grasped the importance of what had occurred. Settlers understood that the assembly allowed them to have a hand in governing themselves, but they were motivated more by opportunities to approve laws sent by the Virginia Company from London and to propose their own legislation rather than by abstract concepts of self-government or subjects rights and liberties. Equally, no documented discussion took place in the colony about the morality of owning and enslaving Africans. Deliberations in future general assemblies at Jamestown, as mirrored later in colonial legislatures

Yet the coincidence of the meeting of the first representative government and arrival of the first enslaved Africans in the summer of 1619 was portentous. Historians have argued that the rise of liberty and equality in America, Americas democratic experiment, was shadowed from its beginning by its dark obverse: slavery and racism. Slavery in the midst of freedom, Edmund Morgan writes, was the central paradox of the birth of America. The rapid expansion of opportunities for Europeans was made possible only by the enslavement and exploitation of African and Indian peoples. Non-Europeans were consigned to a permanent underclass excluded from the benefits of white society, while Europeans profited enormously from the fruits of the labors of those they oppressed. Arguably, then, 1619 marks the inception of the most important political development in American history, the rise of democracy, and the emergence of what would in time become one of the nations greatest challenges: the corrosive legacy of racial stereotypes that continues to afflict our society today.

D ESPITE THE SIGNIFICANCE OF 1619 AND SURROUNDING years, this period is almost entirely unknown to the public. Insofar as any attention has been given to early Virginia, the

Owing to numerous setbacks, the Virginia colony struggled in its early years, leading the Company to introduce wholesale reforms in an effort to save the colony from collapse. Still largely an experimental period in Englands empire-building trajectory, the import of 1619 derives from the consequential philosophical and political assumptions that guided the reforms, though they in turn led to unforeseen and tragic outcomes that ultimately brought an end to the project. Instigated by the highly respected parliamentarian and leader of the Virginia Company, Sir Edwin Sandys (pronounced Sands), propertied white males in the colony were granted remarkable political freedoms as well as opportunities to share in the running of their own affairs. In addition, plans were put in place to promote a harmonious society where diverse peoples and religious groups would live together side by side in peace to their mutual benefit. Because so many influential parliamentary leaders were involved with the Company, proposals for Virginia were informed by the wide-ranging political debates taking place simultaneously at James Is court and in Parliament, which linked developments in the fledgling colony to domestic and international issues of momentous consequence. By 1619, the Virginia Company was recognized by many in high political circles as a laboratory for some of the most advanced constitutional thinking of the age.

Company leaders grounded their efforts to establish a godly and equitable society in the philosophical theory of the commonwealth. The term commonwealth, or the common weal, emerged in Europe in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and brought together a variety of political and economic precepts that highlighted the common good of the people. Particular emphasis was given to the importance of wise and noble rulers and mixed governmenta salutary balance of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracyas well as Christian morality, prosperity, and social well-being. Linked to Renaissance humanist ideas, statesmen and intellectuals believed that the application of rational approaches to government and social and economic organization would encourage the improvement of societies and the human condition. Where better to test these ideals than the New World? In Virginia, commonwealth theory guided the leaderships approach to every facet of the emerging colony, including government, the rule of law, protections for private property, the organization of the local economy, and relations with the Powhatans, the Indian peoples whose territories surrounded English settlements. The great reforms introduced in 1619, therefore, were all-encompassing, not directed simply toward the creation of a legislative body.