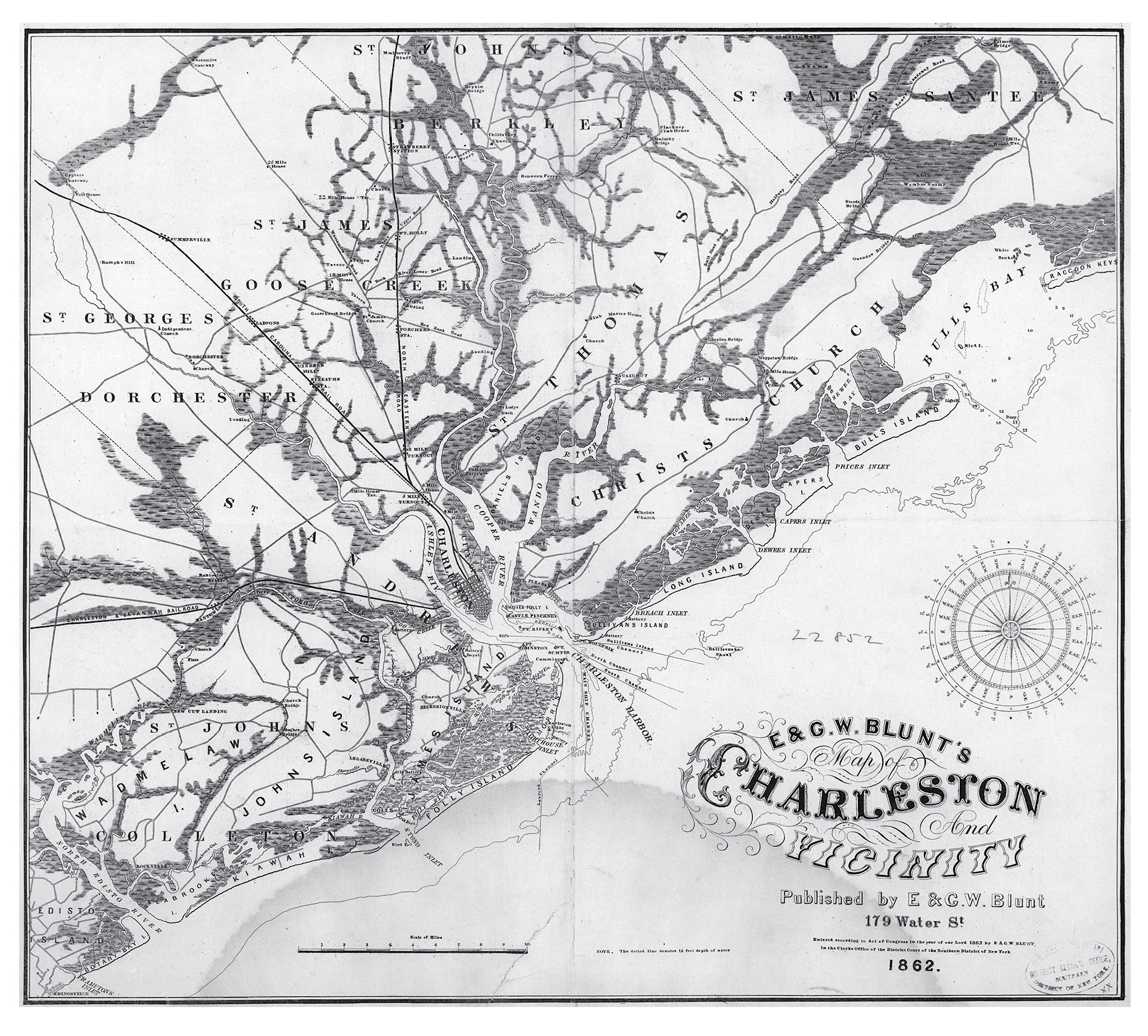

Charleston and Vicinity.

T he note arrived in Washington on the 14th of February 1862. The war between North and South was still less than a year old. The author was Brigadier General T. W. Sherman, not to be confused with the William Tecumseh Sherman of later, war-making legend. T. W. Sherman, based at Port Royal off the South Carolina seacoast, had a question for his commanding officer in Washington, George B. McClellan, general in chief of the Union Army.

With Confederate forces pressed upon the federal capital, McClellan had much to occupy his anxious mind. The Union had won no important victories, and legions of critics wondered just when he planned to go on attack. What T. W. Sherman wanted to know was this: Should a siege be put to Savannah, the port city some thirty miles to his immediate south in Georgia? Or should he instead train his sights on South Carolinas port of Charleston, some fifty miles to his north?

A look at a map of supply routes and the concentrations of forces suggested no obvious answer. In truth, neither Savannah nor Charleston had much value in strict military terms at that time. The cities able-bodied men had gone off to battle, leaving behind the women, the children, the elderly, and the slaves. The fighting action in the war was in Northern Virginia and in forts strung along the rivers of Tennessee. But it was not I would be glad to have you study, he told his subordinate. The greatest moral effect would be produced by the reduction of Charleston.

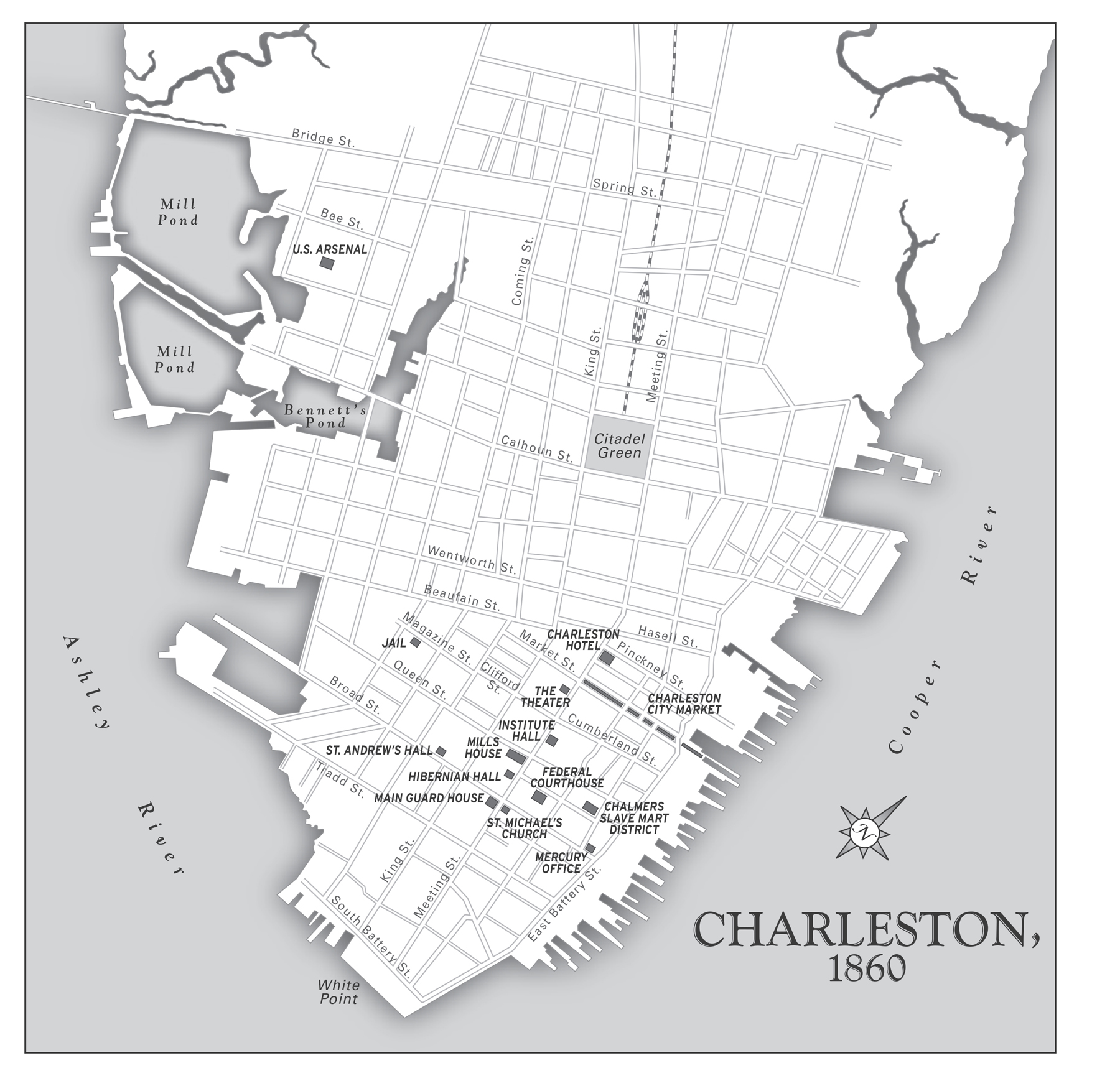

By reduction, McClellan meant the levelling, or, in still plainer words, the destruction of Charlestona city of some forty thousand inhabitants. The city was densely packed with homes, from three-story mansions stuffed with fine European art to backyard slave cottages as well as dozens of churches and a handful of synagogues, schools for children and college students, hospitals, corner groceries, outdoor market stalls, scores of saloons, numerous gambling dens and brothels, a theater, and a few large meeting halls. In theory, the job could be accomplished without a single Union soldier even planting a boot on Charlestons streets by means of the cast-iron Parrott gun, capable of firing ten-pound projectiles from a mile away. The aim might not be great from that distance, but accuracy was not particularly important when the goal was simply to hit something, anything, in the city. The blunt purpose was to induce terror through the indiscriminate nature of the assault. Perhaps a shell would hit the jail on Magazine Street, where the inmates shared quarters with the rats, or, then again, strike the Orphan House on Boundary, Americas first public orphanage, where the cornerstone had been laid by President George Washington himself.

As for the greatest moral effect, McClellan meant an object lessonof an inspirational and gratifying message to the North and of a cold, brutal warning to the South to lay down its obstinate arms. Charleston, he believed, was fit for a singularly severe punishmentmore deserving of payback than anywhere else in the traitorous South was. This, too, McClellan took pains to convey to T. W. Sherman. There the unnatural hatred of our Government is most intense, he said. There the rebellion had its birth.

M onday, October 17, 1859: The news flash arrived out of Baltimore at Perry OBryans American Telegraph Office on Broad Street in downtown Charleston. As always, OBryans team hustled the dispatch, which they translated from Morse Code, over to the newsroom of the Mercury a few blocks away. The item ran in the papers Tuesday edition, at the top of page three, in the Latest by Telegraph feature, dateline Baltimore. , the report said, of a serious insurrection at Harpers Ferry, Va. The trains were stopped, telegraph wires cut, and the town and all public works were in the possession of the insurgents. All statements concur that the town is in complete possession of the insurgents, together with the Armory, the Arsenal, the Pay Offices and the bridges. The insurgents are composed of whites and blacks, supposed to be led on by abolitionists.

Rumor hardened into fact. The ringleader of the assault on Harpers Ferry was John Brown, a Connecticut-born, militant opponent of slavery who had waged bloody attacks on proslavery settlers in Kansas several years earlier. Brown was quickly captured by US Marines, who killed many of his cohorts, and within thirty-six hours, the insurgency was put down. The