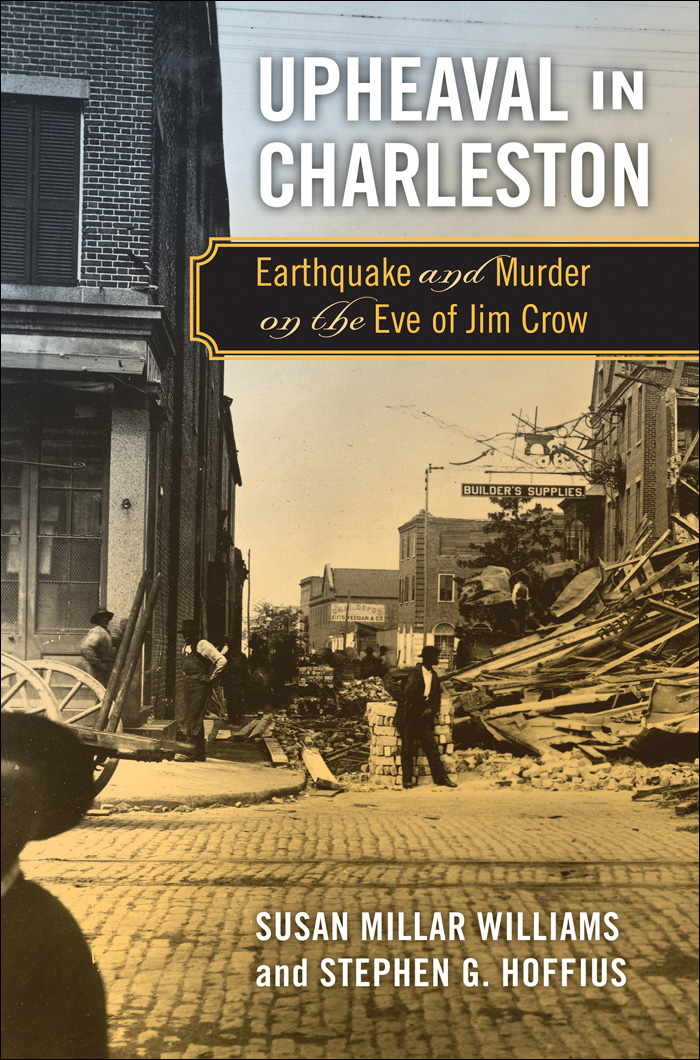

UPHEAVAL in Charleston

EARTHQUAKE AND MURDER ON THE EVE OF JIM CROW

Susan Millar Williams

Stephen G. Hoffius

Publication of this work was made possible, in part, by a generous gift from the University of Georgia Press Friends Fund.

Published by the University of Georgia Press

Athens, Georgia 30602

www.ugapress.org

2011 by Susan Millar Williams and Stephen G. Hoffius

All rights reserved

Designed by April Leidig-Higgins

Set in Arno by Copperline Book Services, Inc.

Printed and bound by Thomson-Shore

The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in the United States of America

15 14 13 12 11 C 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Williams, Susan Millar.

Upheaval in Charleston : earthquake and murder on the eve of Jim Crow / Susan Millar Williams and Stephen G. Hoffius.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8203-3715-9 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-8203-3715-3 (hardcover : alk. paper)

1. Charleston (S.C.)History19th century. 2. Charleston Earthquake, S.C., 1886Social aspects. 3. Charleston (S.C.)Race relationsHistory19th century. 4. Charleston (S.C.)Social conditions19th century. 5. African AmericansSegregationSouth CarolinaCharlestonHistory19th century. 6. Dawson, Francis Warrington, 18401889. 7. MurderSouth CarolinaCharleston. I. Hoffius, Stephen G. II. Title.

F279.C457W55 2011

975.7915041dc22 2010045462

ISBN for this digital edition: 978-0-8203-3958-0

FOR

Dwight Williams and Susan Hoffius

Preface

LIVING WITH DISASTER

Susan Millar Williams

CHARLESTON HAS ALWAYS stood on shaky ground. Vulnerable to the fury of nature and the brutality of man, the old port city has served as the stage for the major acts of the great American drama. It landed more enslaved Africans than any city in the original thirteen colonies, reaped a vast fortune from their labor, surrendered to the British during the Revolution, led the charge for secession, and fired the first shots of the Civil War. When that war was lost, the city was occupied by federal troops and bound by U.S. laws that turned the states racial hierarchy on its head.

By the early 1880s catastrophe had become a way of life. Wars, hurricanes, fires, floods, epidemics, and riots had come and gone. Most black Charlestonians had endured the galling yoke of slavery, as had their parents and their parents parents. Most white men over the age of forty had fought and bled in the Civil War. The city was burdened with more than its share of widows and orphans. The citizens of Charleston, white and black, thought of themselves as survivors.

On August 31, 1886, the city was struck by a new and unforeseen calamity: the most powerful earthquake ever recorded on the east coast of North America. Buildings collapsed, dams broke, railroad tracks buckled and derailed trains. Fissures split the ground and water spouted two stories high. Miraculously, fewer than one hundred people died, though many more were injured.

The terror of the experience stayed with people all their lives.

I FIRST STARTED thinking about the earthquake in 1988, when one of my students at the College of Charleston wrote a research paper about it. She simply intended to find out what had happenedwhat fell down, who was injured, how people coped. Instead, she uncovered conflicts that surprised us both. Why were whites so angry when black people prayed and held religious services in the public encampments? Why would a white Episcopal minister threaten to beat a black woman with his walking stick if she didnt stop singing hymns? Why were the police called to halt a childrens baseball game? These were intriguing questions, but they seemed extremely remote from my life.

A year later, on September 21, 1989, Hurricane Hugo flattened parts of my little town, McClellanville, thirty miles north of Charleston, and left the rest looking like a French battleground after World War I. My house weathered the winds and the twelve-foot storm surge; the homes of many of my friends did not. Life as we had known it was swept away.

I still catch myself referring to something that happened during the storm when what I really mean is five months, or ten months, or even eighteen months later. Only on the nightly news does disaster pass quickly. And when I recall the long trudge back to normality, the memories that haunt me are not the images that show up on television every year on September 21shrimp boats in the streets, a house that floated fifty yards from its foundationor the ones in our family albumumbrellas poking through holes in the roof, my baby daughter climbing a mountain of donated sweet potatoes, dead fish on the front steps. Instead I remember feeling flayed alive, and knowing that everybody else must feel that way too. It was as if the storm had stripped away every shred of the emotional padding that, in normal times, allows people to ignore pain, smile politely, and go about their daily routines. There was a sense that help would never come, that we were doomed to spend the rest of our lives foraging in the wilderness.

Help did come, of course. Lots of help. Huge trucks rolled into town carrying water, ice, donated socks, diapers, mattresses, generators, even sofas. Volunteers and National Guardsmen wielded chainsaws and power washers.

But almost before the first bag of ice had melted, suspicion and greed set in. The storm hit in the middle of a prolonged fight over whether to establish a new public school in the heart of the village. Many whites supported the local private school, established to resist integration, and they loudly opposed the idea. Blacks and whites who favored public education saw the struggle as a crusade for equal rights. And far from laying aside their differences after the storm, these factions quarreled more bitterly than ever.

Perhaps it is a natural human impulse to want to help the people most like oneselfafter all, the basic motive behind relief efforts is the knowledge that something like this could happen to you. Yet I was shocked when white people in vans tried to press diapers and baby clothes on me and visibly recoiled when I suggested they take their donations to Lincoln High School, where harder-hit black residents could get them.

I sometimes found myself thinking about the earthquake and wishing I knew more. But I was working on a biography of the novelist Julia Peterkin, who revolutionized American fiction in the 1920s by writing seriously about the lives of black farming people. As I labored to pin down the source of her subversive genius, the struggles Peterkin dramatized were playing out all around me. Blacks and whites inhabited the same expanse of earth but lived in different worlds. The trauma of the disaster itself was magnified by the experience of subsisting in a blasted landscape, looking, day after day, at splintered trees and mangled houses. Two decades after the storm, these images still appear in my dreams.