Contents

Copyright 2015 by Christopher Dickey

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN is a registered trademark, and the Crown colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dickey, Christopher.

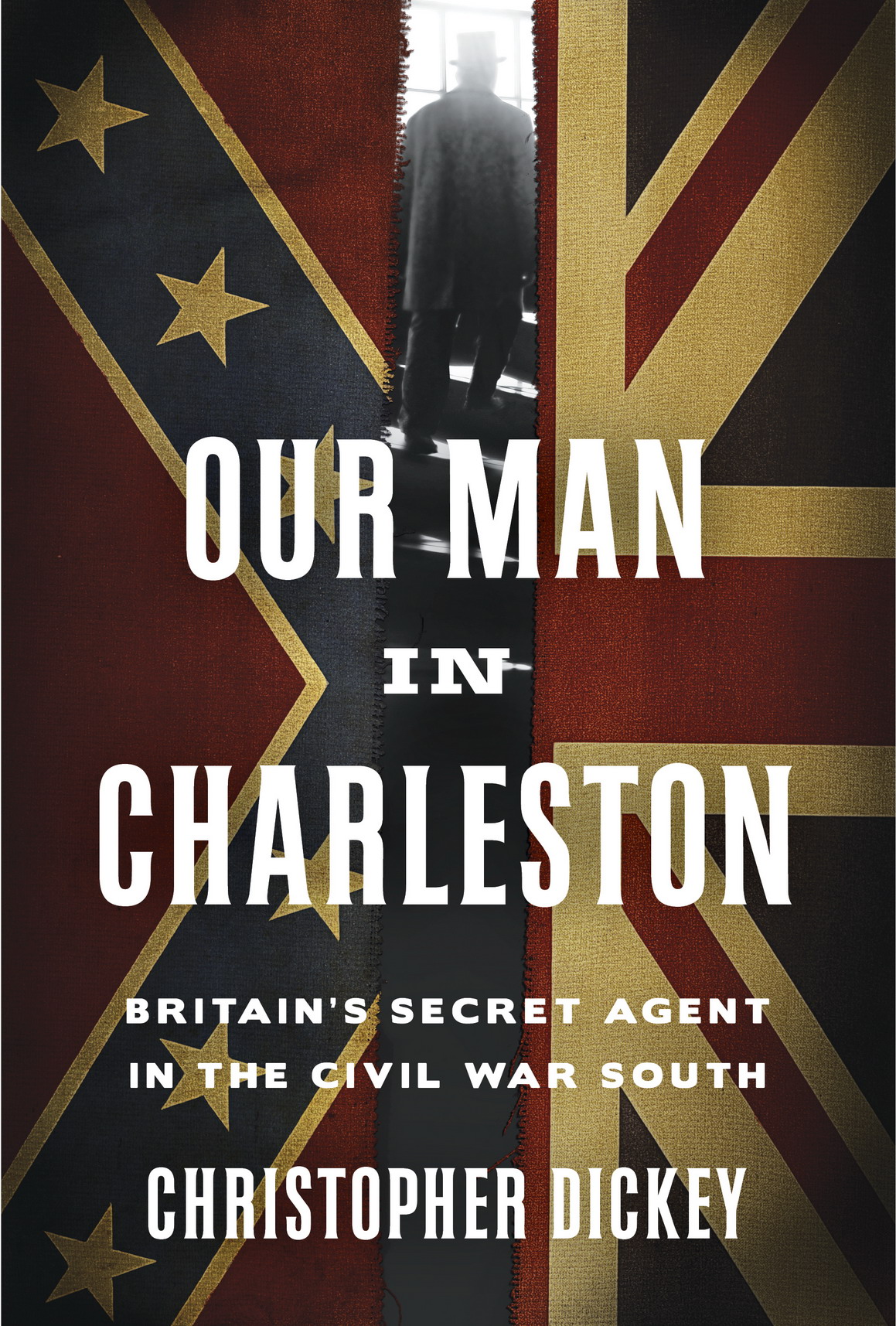

Our man in Charleston : Britains secret agent in the Civil War South / Christopher Dickey. First edition.

pages cm

1. Bunch, Robert, 1820 2. DiplomatsGreat BritainBiography. 3. SpiesGreat BritainHistory19th century. 4. EspionageGreat BritainHistory19th century. 5. Diplomatic and consular service, BritishUnited StatesHistory19th century. 6. Diplomatic and consular service, BritishConfederate States of America. 7. United StatesForeign relationsGreat Britain. 8. Great BritainForeign relationsUnited States. 9. Confederate States of AmericaForeign relationsGreat Britain. 10. Great BritainForeign relationsConfederate States of America. I. Title.

E469.D53 2015

973.786092dc23

[B]

2015016637

ISBN9780307887276

eBook ISBN9780307887290

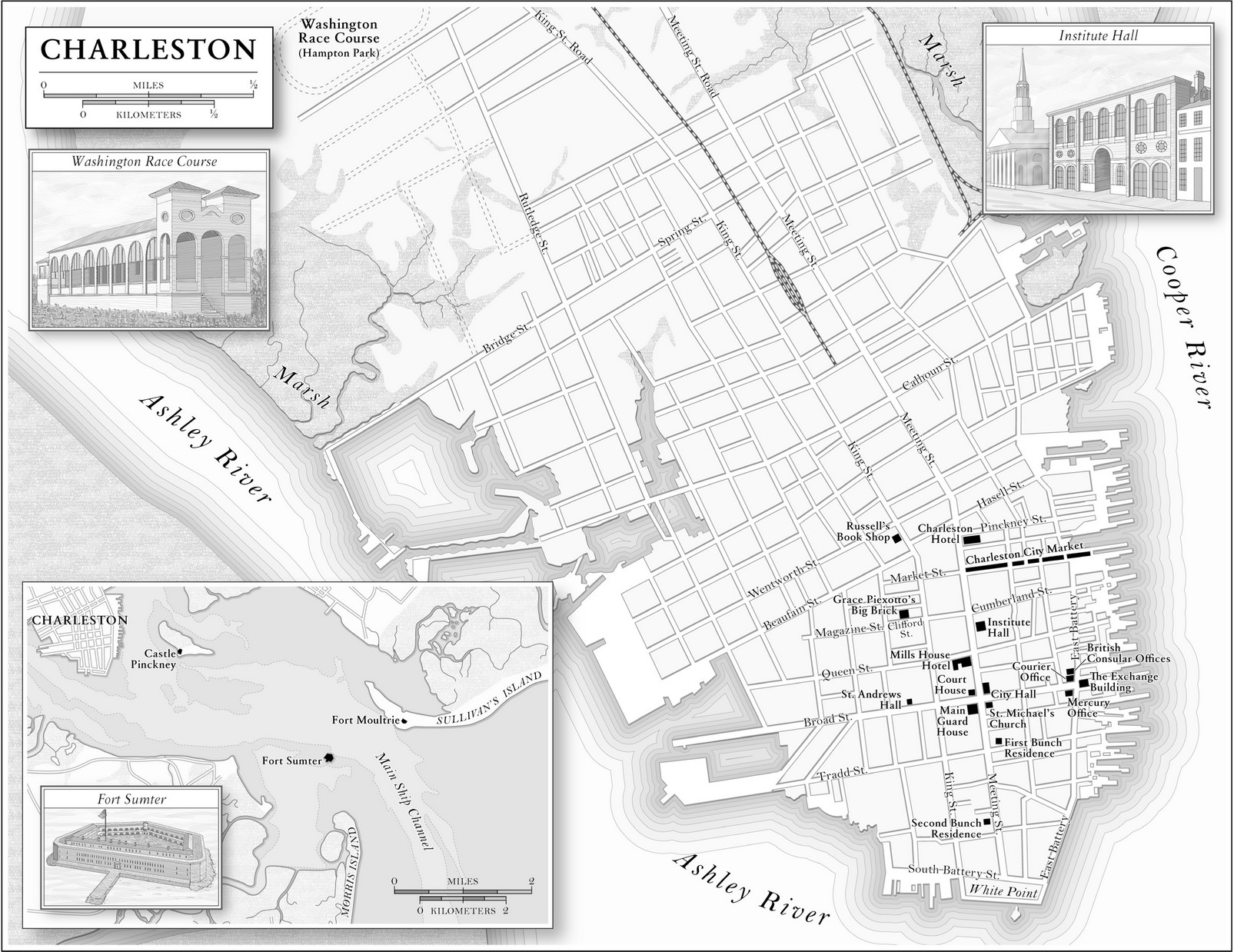

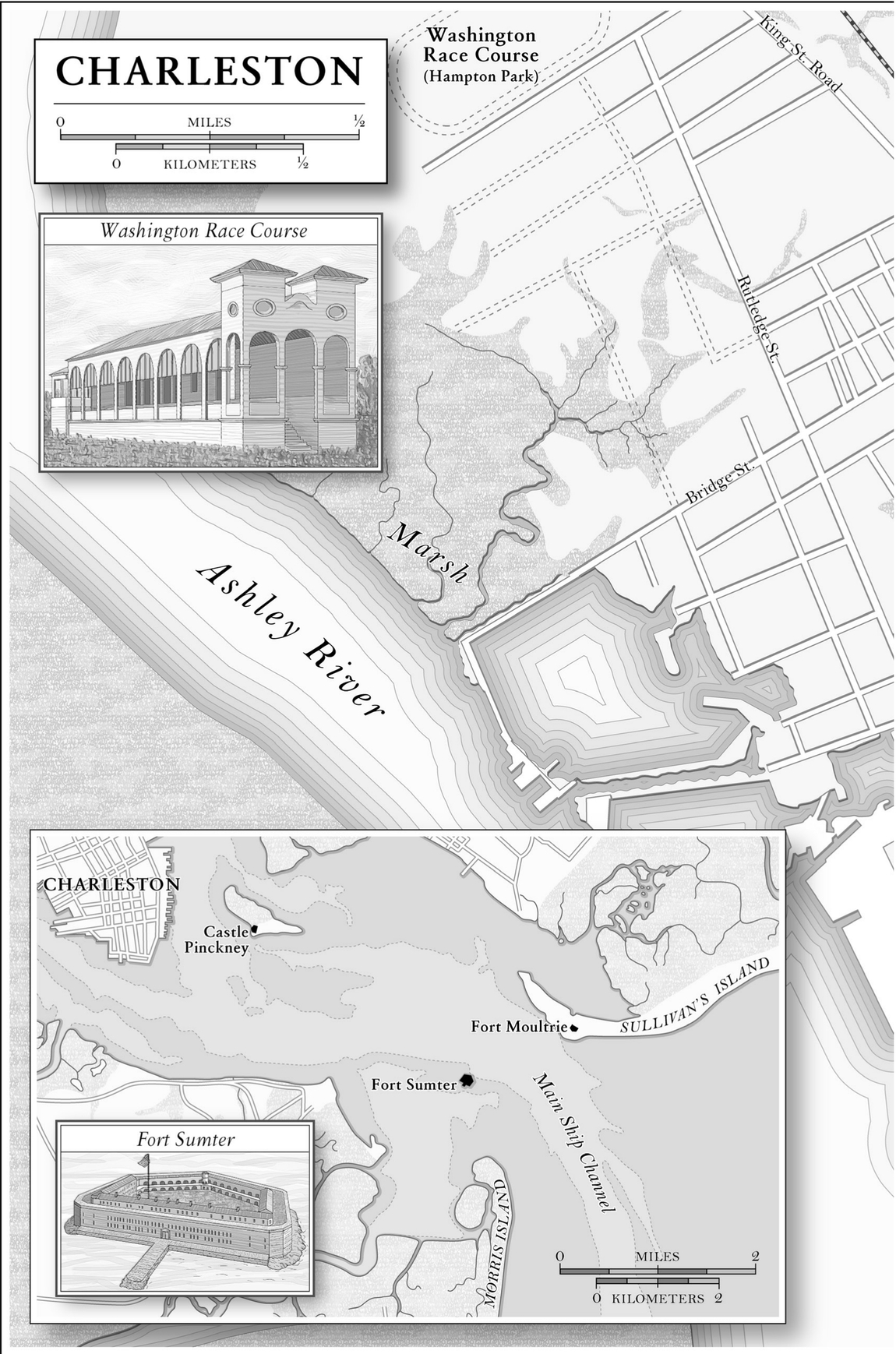

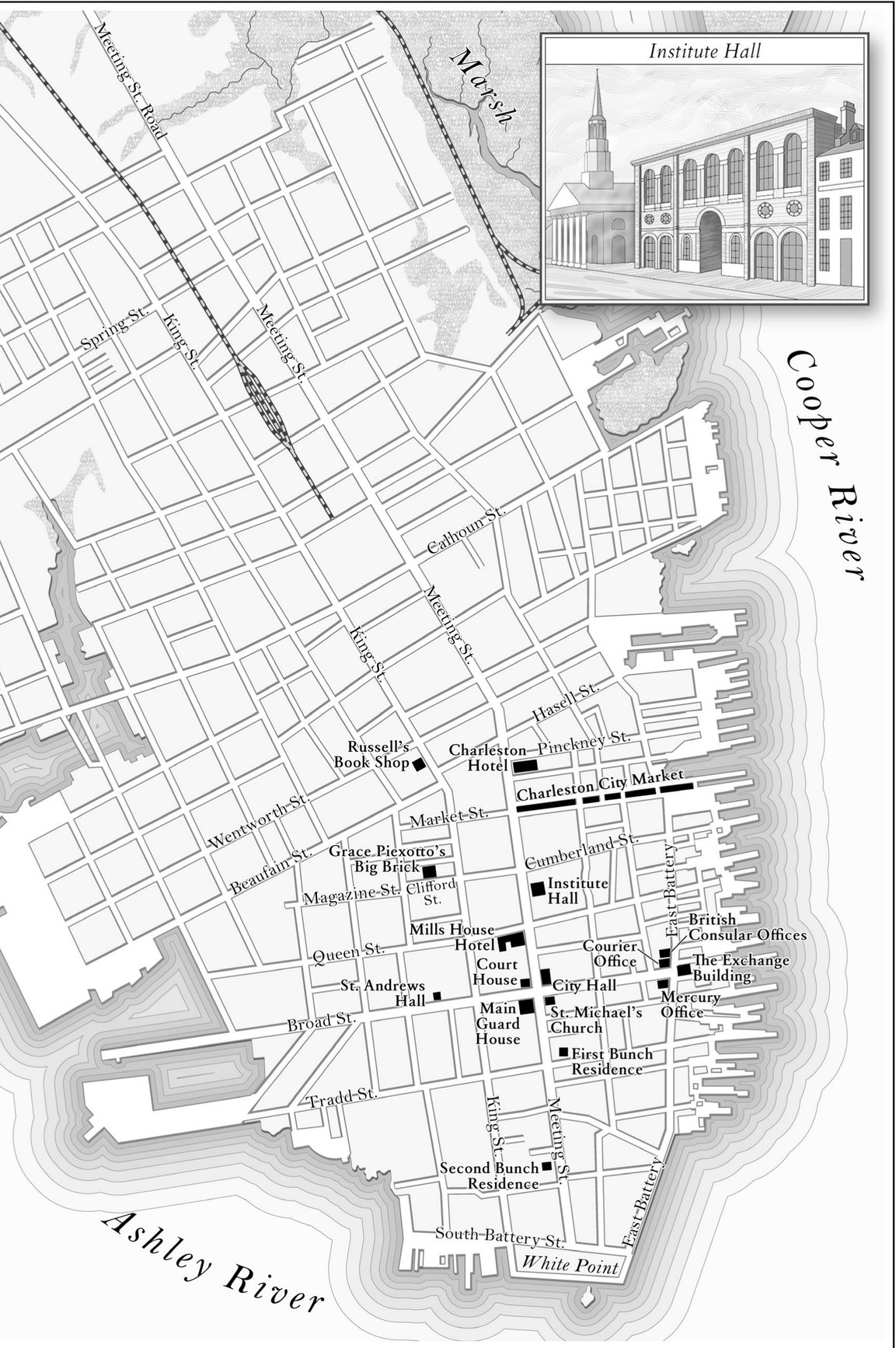

Map: David Lindroth

Title page photograph: Illustrated London News Ltd/Mary Evans Picture Library

Title page and part opener art: Marilyn Volan/Shutterstock

Cover design: Christopher Brand

Cover photographs: (figure) Maggie Brodie/Trevillion Images; (tape strip) Andrew Rich/Getty

v4.1_r1

a

For my grandchildren

Elise, Calvin, Cecily, and Jason

learning from the past;

looking to the future

CONTENTS

We have seen, at every step, that every defiant movement of Slavery was a stab at its own heart.Its animal ferocity evoked the energy which crushed it.

Westminster Review, London, 1865

I must dissemble.

British Consul Robert Bunch, Charleston, South Carolina, 1856

Prologue

W ILLIAM HOWARD RUSSELL, ON ASSIGNMENT for the Times of London to cover the American War Between the States, was up late drinking on the riverboat Southern Republic as it cruised with the current on its way down from Montgomery to Mobile. The evening was warm and felt a little lazy that May of 1861. People were talking a lot about fighting as the War of Secession gathered momentum, but, at that point, few were dying. Russells barroom companionsrich planters and parvenu businessmendeclaimed for hours, whiskey in hand, about Yankees and slaves and the Southern struggle for independence from the North until the air grew heavy with the burning tar of bad cigars, and electric with armchair bravery. We will never be conquered, one would say. There is nothing on earth that could make us go back into the Union, another proclaimed. We will burn every bale of cotton, fire every house, and lay waste every field and homestead before we will yield to the Yankees!

Captain Timothy Meaher, the boats owner, was drinking with the rest of them, and he focused his cunning gray eyes on Russell. Meaher figured the foreign journalist might not understand the way folks did things here in America, so close to the old frontier. White men had claimed this land, and white men had brought it civilization, and men like Meaher had made their fortunes here doing whatever needed doing to get ahead. Not so long ago, said the captain, there were a lot of Indians along the river. But the settlers had trapped them on a bluff high above and starved them into surrendering. They were so desperate that, when the white men told them they could leave on boats, the Indians believed them. And once they were on the river, the white men, well, they just shot the hell out of them, Meaher said. Slaughtered hundreds!

Russell was not much impressed. He knew Meahers type. The captains blood was Irish, and Russell, who was Irish too, figured it was County Kerry blood. He could tell from Meahers square jaw and full lips. The captain was rawboned and rough and looked as if he could handle himself in a brawl. He liked to tell tales, and tall ones, and he could be intimidating even when he was having a laughmaybe especially when he was having a laugh.

The other guests harrumphed their approval and raised their glasses to Meahers story about pioneer bravado, but Russell knew that the coming fight with the Union Army would be like nothing these men had seen or imagined before. Over the previous decade Russell had made his reputation as a correspondent witnessing the carnage in the Crimea, where the British and the French had fought the Russians. His dispatch about the charge of the Light Brigade had captured the imagination of the world; his descriptions of the grotesque suffering of the sick and wounded soldiers had horrified it. Russell had covered the uprising in India that almost cost Britain the heart of its empire, and he had seen and reported the savagery on all sides. He had slept many timestoo many timeson battlefields where the air stinks of blood.

What Russell thought about this war in America in May 1861 was that it would be long and savage in the way that only modern warfare could be. Killing would take place on an industrial scale. The South had seceded. The North had declared it would fight to preserve the Union. Tens of thousands of troops were being called up, and histrionic headlines shouted about battles won and lost. But there had been, as yet, nothing more than skirmishes. Even the shelling of Fort Sumter, which had officially started the shooting war a few weeks before, had ended with the surrender of the Federal garrison before anyone was killed. Such battles were making for a lot of bourbon-fueled bravado, but they wouldnt decide the conflict.