The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This book is dedicated to the writers, not only those in my family, but all the writers throughout history, those who have set down our stories so that we can remember and understand them, and then rewrite them.

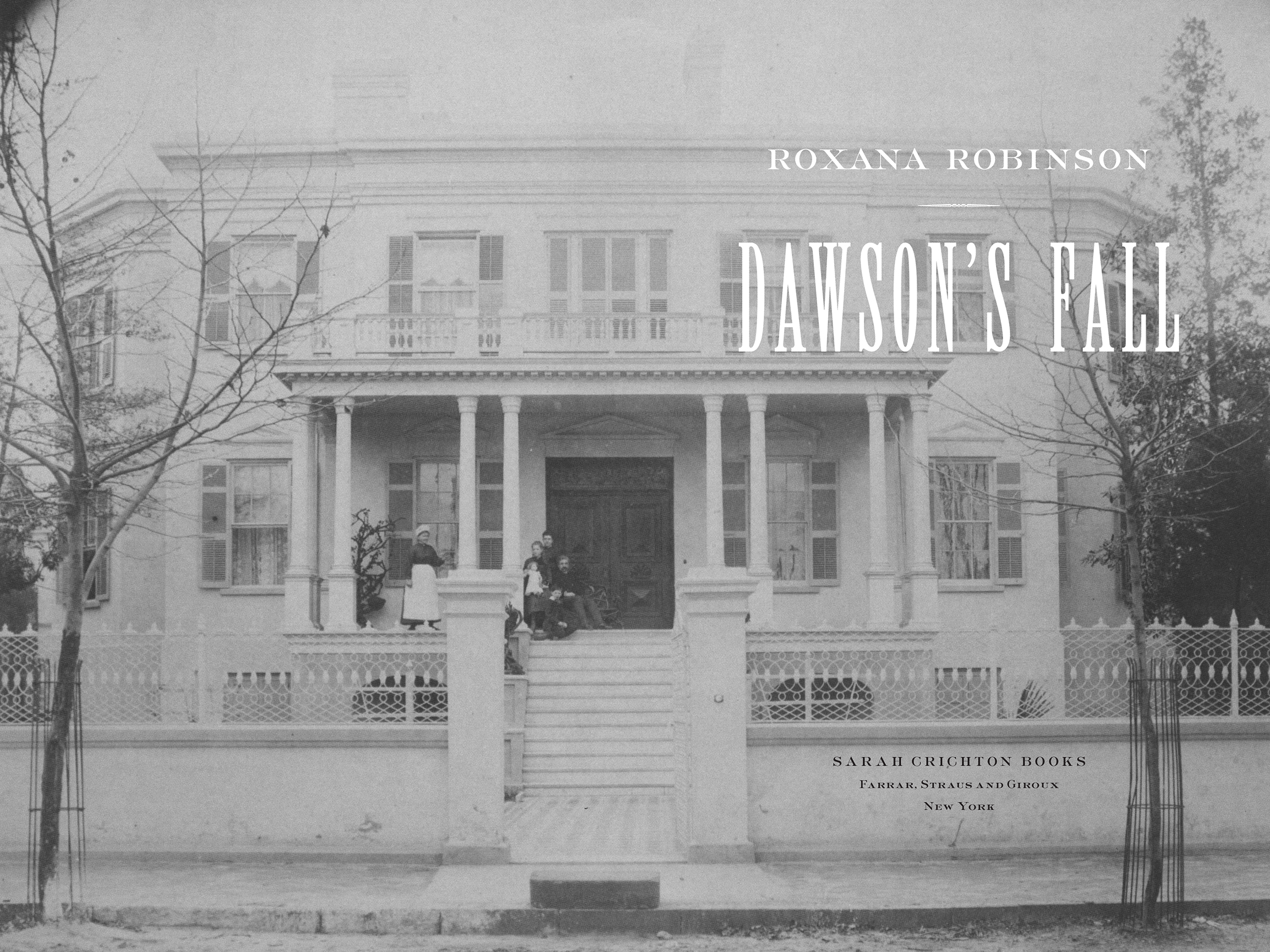

Francis Warrington Dawson and Sarah Morgan Dawson are my great-grandparents. I grew up hearing stories about them.

All families have origin myths: we tell our stories to remind ourselves of who we are. The stories are handed down through the generations to reinforce our beliefs about ourselves.

One of my ancestors came here from Wales in the seventeenth century. He wrote this message in the family Bible:

I, David Morgan, Gentleman of Wales, bequeath to my descendants in America, this comfortable certainty; they come neither from Kings nor nobles, but from a long line of brave gentlemen and women with unstained names. [I am] son of Evan, and grandson of David, gentleman of Wales, whose ancestors returned to its mountains rather than be enslaved by William of Normandy, called William the Conqueror.

Principle is important in my family. I wasnt surprised to learn that my Welsh ancestors had moved into the mountains rather than submit to a foreign invader. But I was surprised by the dates: William the Conqueror arrived in England in 1066. This means that the Morgan family had been telling this story, handing it down from generation to generation, for seven hundred years. Clearly it was an important part of who we were.

WE WERE TAUGHT that principle was more important than money or comfort or peer pressure, that conscience was a reason to act. My parents converted to Quakerism; my brother did community service during the Vietnam War. Our family believed in honoring your conscience.

My mothers family had deep roots in New England. Many of them arrived in that early surge of searchers for a place to practice the religion they chose. Religion played a big part in my mothers family. Many were ministers, and many were outspoken: Lyman Beecher and his son, Henry Ward Beecher, my great-grandfather. Harriet Beecher Stowe was my great-great-great aunt. We spoke out for what we believed in.

My fathers side of the family had roots both in New England and in the South. Principle played an important part in that history as well: one ancestor had been put to death by Henry VIII for his loyalty to the Catholic Church.

But the story of my Southern family and their principles was more complicated than that of my New England family because of slavery. I couldnt ignore its presence. All Southern families, regardless of their race, who trace their bloodlines back before the Civil War are affected by the presence of that peculiar institution. They may not mention it, but it helps shape who they are. My great-grandfather Frank fought for the Confederacy, and my great-grandmother Sarah grew up in a privileged household in antebellum Louisiana. Certainly slavery played a part in their lives.

So I wondered about this. How did people of principle navigate the ethical maelstrom of slavery? How could they maintain personal integrity during that dark basilisk reign, or during its terrible aftermath?

Frank and Sarah were both writers, so I could read their thoughts in hundreds of pages of editorials, essays, letters, and journals, both published and unpublished. They wrote about their joys and excitements, grieved over their losses, set down their hopes and fears, and told their own moving and tender and hair-raising stories. But in one sense, even before I read their stories I knew who they were: they had bequeathed their beliefs to me. I was the recipient of the family culture, I was part of it.

I wanted to learn more. I wanted to learn how they had maintained the code of honor of my Welsh ancestors. I wanted to learn and tell their story, a modern version of the one my family had been telling for seven hundred years. How we had climbed up into the steepest, most inaccessible mountain heights rather than give up our principles. If we had.

HERE IS THAT VERSION. All the facts in it are true as far as I could determine. All the letters and diary entries are real, as are all the other published sources.

As a biographer, I hewed to the facts, even when they made me uncomfortable. The language, words, and attitudes are drawn from published and unpublished material. These are sometimes shockingly racist, reflecting the reality of those shockingly racist times. As a novelist, I wrote this as a living, breathing tale, one that unfolds to span the lifetimes of my great-grandparents. Frank Dawson was born in England and Sarah Dawson died in France, but they are both buried in Charleston, South Carolina, where they spent their happiest years together.

March 12, 1889. Charleston, South Carolina

HE WAKES AS HE IS FALLING.

He feels himself plunging into space, a great wheeling emptiness below. Hes been on the edge of a cliff, grappling with a man trying to shoot him. Dawson grabs him, wrestling for the gun, but he wrenches away, pulling Dawson off-balance. The man presses the gun against Dawsons chest; he hears the great enveloping sound of the shot. Then he feels the sickening shift beneath his feet as he loses his grip on the world.

As he falls Dawson grabs the mans shoulder to save himself, but instead pulls the man over with him. They fall together, still grappling, as though holding on to each other will help. Dawsons body is clenched and tight, muscles still focused on what he just had, solid ground beneath him, but instead there is this: the long drop into whistling black.

Dawson sits up, sweating.

Hes in the narrow bed in his dressing room. His thrashing has pulled the sheets loose, and his feet are now tangled and trapped. The room is dim and shadowy, the curtains drawn for the night. The patterned wallpaper, the tall mahogany bureau, the brass bedstead are all familiar but irrelevant. Hes still in his nightmare, heart hammering. He still feels the terror of pitching into space, the bodys last clenching try at holding on to life. He still feels the mans coarse sleeve in his grasp, smells his sour rankness. The sound of the gunshot still explodes in his ears.

He kicks his feet free and gets up. He goes through the connecting door into their bedroom, where his wife lies submerged in the big mahogany bed, nearly hidden by pillows.

She lifts her head and sees his face. What is it?

The struggle is still running through him. He takes a breath and shakes his head. In his body, its still happening. He begins walking up and down the room. This is familiar, too, the mirrored armoire, the high sleigh bed, the dressing table. Also irrelevant in this swift current of feeling.

Whats wrong? Sarah sits up, the white nightgown crumpled high around her throat.