Contents

I turned the page and slowly read

The yellow paper stained and old

Marked what leaf was fairly writ

Which was blotted and half told

Of weariness or grief or joy

The hand had felt in its employ

and where, at length, the pen was stayed

and lifes last entry weakly made.

The story of a life was there

An echo of the old refrain.

I knew I would not find enscribed

The thoughts of night, the words of prayer

The looks of love or hate and all

That made life truly dark or fair

All, all had faded in the night

Save what poor outline here was spared.

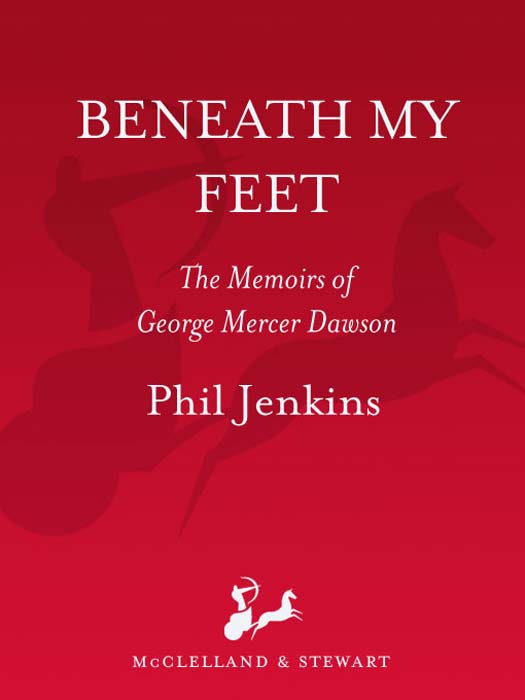

G EORGE M ERCER D AWSON .

written on the shore of Francois Lake,

British Columbia, 1876

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

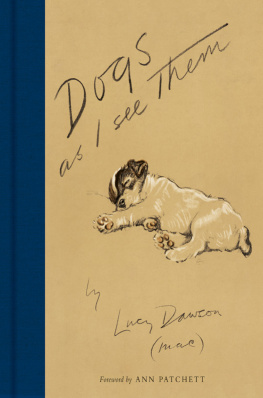

The illustrations on the following pages are the personal works of Mr. Dawson: Chapter 1: The Age of Growing, Chapter 2: The Age of Learning, Chapter 4: The Age of the West, Chapter 4: The Age of the West, Chapter 5: The Brief Span of the Heart, Chapter 6: The Age of the North, Chapter 6: The Age of the North

BY WAY OF EXPLANATION

I FIRST ENCOUNTERED the subject of this book, George Mercer Dawson, in 1988, on the wall of a small rural museum in southern Saskatchewan, near the United StatesCanada border. A photograph, dated 1874, portrayed a group of men involved in the Joint Commission charged with mapping the border in that and the previous year. Twenty-four-year-old George Dawson was a Canadian naturalist, botanist, and surveyor with the Commission. In the photograph, Dawson stands among a group of large, bearded Mtis guides, all of whom are a good foot and half taller than he.

Intrigued, I did further research and discovered that all of the Dawson family correspondence was catalogued and indexed at the McGill University archives in Montreal. This treasure trove was the result of George Dawsons father, John William, having been the Principal of McGill for almost forty years. There are around five thousand of Georges letters in grey archival boxes, from the letters he wrote to his grandfather as a boy, to one he wrote to his beloved sister Anna only a few days before his death, when he was head of the Geological Survey of Canada. As well, there is a wealth of his photographs, poems, diaries, journals, and sketches.

Clearly a book was in order, a biography. There was already a fine retrospective collection of his letters published by his niece, and a couple of slim life stories aimed at adolescents, but no comprehensive telling of the tale of this extraordinary Canadian. And so it began.

In the telling, however, I soon became aware that an unusual approach was needed. George Dawson was a wonderful read. He was a writerin his personal letters and even in the published reports of his travelsof endearing wit, evocative description, and illuminating fact. I found myself quoting from him every other sentence and realized that, for the reader, this rhythm would be like riding a cart down a corduroy road. Better to get out of his way.

When I returned to the letters and laid them out in a narrative line forty-five years long, it emerged that Dawson had almost told his own life story. After leavening in his descriptions of his professional career, I could see he had effectively written his memoir; it had simply never been assembled. So, I appointed myself his ghost writeralthough he, not I, was the ghostand the memoir grew. Dawson himself had suggested, in a letter written near the end of his life, exactly such a course for a first draft autobiography his father had not completed, advising that a literary man be brought in to knock the thing into shape. To provide a frame for his story, I added, taking as much care as possible to build only on the facts, an opening in which Dawson describes starting the memoir, and gives his reasons for doing so.

In creating a coherent narrative, parts of some letters were moved to the times they described, similarly there was some rearrangement of his more thoughtful notes to ensure a narrative flow. Key events during his life on which I could find only passing comment, such as the death of Darwin, were expanded. Finally, I inserted samples of Dawsons nature poetry, and a small selection of his vast output of photographs, watercolours, maps, and notebook sketches.

Every fact in this memoir is Dawsons fact, as is every description of his travels. I would estimate close to ninety-five per cent of the book is written in his own words, tidied up to best tell the story of a man who led a heroic life, and who deserves to have his story on as many bookshelves as possible. Thank you, George, for your literary legacy.

BY WAY OF INTRODUCTION

April, 1900 Ottawa

W ERE YOU TO TAKE the measure of me, pass a surveyors line from my toes to the tip of my head, it would record the height of a lad of twelve, though I am now past fifty. However, had the string been secured to my ankle in the May of 1869, when I set sail from Montreal for England to become what I am now, a natural scientist, it would have unspooled many thousands of miles, tracing a line of travel through the New World and the Old, and arriving here, anchored to the leg of a desk in the offices of the Geological and Natural History Survey of Canada. The desk where I now struggle to start a literary assay of my days.

I have had the fortune to publish many papers on the personality of the good earth, reports on glaciers, dinosaurs, Indians, gold, and coal, and I have kept pace by pace journals of my travels, compiling them into reports that stretch along the shelves of the Survey library. I could place several volumes of minor poetry alongside them, and yet the commencement of this memoir has been a hard vein to mine.

It is not, to be sure, lack of time that has held me back. True, the affairs of the Survey keep me welded to this chair, until I fear I shall fossilize one night and my colleagues discover a seated statue on the morrow. But such endeavours do not fill a day. I rise as the sun does, no matter where I find myself awakening, and I keep the moon good company, so the day has hours to spare for me. And, I must confess, I am in a state of ennui. Boredoms child, restlessness, is a constant tug at my heel. Perhaps in this expedition into memory I will find relief.

Sitting here with a lamp burning and the inkwell open, I feel again as I did as a child, confined on the wrong side of a window, willing strength back into my spine that I might stand up, walk out, and not cease until I had answered all of natures questions. Instead, I find myself a reference point on the journey of others in this institution. Petty problems are the pebbles of my days, a mound of them piled around my feet. I look into the eyes of an anxious junior surveyor and maintain courtesy, even as I see with my mental eye the wild black glare of a stampeding buffalo as I raise my rifle. Or, attending a departmental meeting, I feel I am standing once more in a swarm of locusts thick enough to choke an ox.