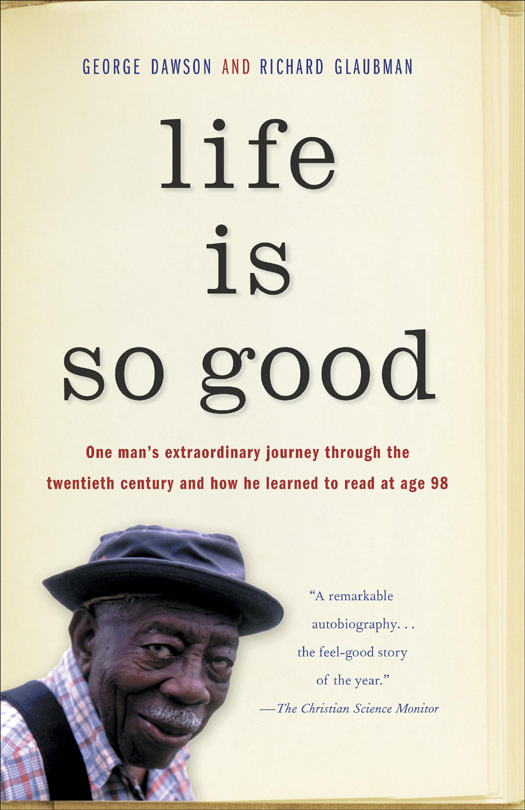

Copyright 2000 by Richard Glaubman

Reading group guide copyright 2013 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Random House and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Random House Readers Circle and Design is a registered trademark of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Dawson, George, b. 1898.

Life is so good/George Dawson and Richard Glaubman.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-375-50530-0

1. Dawson, George, b. 1898. 2. Afro-AmericansTexasMarshallBiography.

3. Afro-American agedTexasMarshallBiography.

4. CentenariansTexasMarshallBiography.

5. Afro-AmericansTexasMarshallSocial conditions. 6. Marshall (Tex.)Biography.

7.Conduct of life. I. Glaubman, Richard. II. Title.

F394.M36 D39 2000 976.4192dc21 99-048834

Random House website address: www.atrandom.com

Cover design: Belina Huey

Cover photograph: Carolyn Bauman

v3.1_r1

Contents

W anting to enjoy every moment, I stared at the hard candies in the different wooden barrels. The man behind the counter was white. I could tell he didnt like me, so I let him see the penny in my hand.

Take your time, son, my father said with a grin. You did a mans work this year.

Putting his hand on my shoulder, he said to the store clerk, Hes all of ten years, but the boy crushed as much cane as I did. Since the age of four, I had always been working to help the family.

I dont know if it was pride from Fathers words or the pleasure from a piece of hard candy that beckoned, but I felt so good I thought I would burst. I had been thinking of those hard candies since my father woke me before daybreak and said, Hitch the wagon. We gonna take some ribbon syrup into town and you comin.

When I went back inside, the stove was going and Ma had a pot of mush cooling. We ate quiet-like so as not to wake the little ones that were asleep on the other side of the room.

I was happy to see they was still sleeping for it was uncommon to spend the day alone with my father. We never had much time to talk and I just liked to be with him.

Two barrels of cane syrup were tied down in the wagon. We sat up front. My father clucked toward the mule. I wanted to tell him that I was glad he was taking me and it was going to be just him and me together all day. Trouble was, I didnt know how to say that in words. So under the shadow of my straw hat, I just looked over at him.

Solid is what I would say. He took care of us. We had potatoes and carrots buried in the straw and salt pork hangin from the rafters. We was free of worries. Papa was a good provider. Someday I would be just like him.

Must have been a couple of hours toward town when my father nudged me. He handed me the reins and unwrapped some burlap. I took a piece of cornbread with a big dab of lard on it. When I commenced to eat, he started talking.

With this ribbon syrup, we be out of debt and have some left for trading. We gonna have seeds for cotton, some new banty chicks, and the fruit trees that are gonna bear fruit next year. No one has the fever and we all be healthy.

Life is good. And with a grin, he added, I do believe its getting better. I liked it when Papa talked to me as a man.

The morning haze had long ago burned off. The wagon stirred up a lot of dust that kind of settled over everything like a nice, smooth blanket. It was good for the mule as the dust had a way of keeping the flies off. Nothing else was said for the next hour, till we came around the last stand of trees and to the rise above Marshall.

In those days, I had in my mind that Marshall was maybe about the biggest and the best place there could ever be. The hardware store had big windows that I liked to look in. I had never been inside since I knew they didnt appreciate black folks with no money. I was partial to the general store, but I liked to walk by the livery stable too. Once a man gave me two bits to rub down and watch his horse for the afternoon. It was 1908, and I hadnt yet seen a car. I had heard of them, but nobody I knew owned one. Papa said that they didnt do too well when the rains came and the roads was deep in mud. Besides, they scared the horses. Mostly, I just liked seeing all the folks from the big ranches and the little farms like ours that was out on the boardwalk.

The cafe and the barbershop was whites only, but I knew a boy that worked in the cafe. And I knew some folks that shined shoes at the barbershop. I liked to look in those windows too.

We never had no cause to go into the post office. But I pictured that one day someone would say there was a letter waiting for me. I would walk past all the folks sitting in the town square beneath the big oak tree. When I was inside, I would say, Im George Dawson. Im here to get my letter. I dont know when that was gonna happen but maybe someday it would. Marshall was a busy place and good things could just happen. It was the county seat and that had to count for something too. At least, thats what I thought then.

But at that moment, in the general store, when my father told me that I could do a mans work, anything seemed possible. I remember everything. I saw the white man frowning, my father grinning at me, and those barrels of candy to choose from. I also remember everything my ears told me that day.

As I picked up a piece of peppermint, I heard a commotion from the street. My fathers gaze followed mine. It was dark and cool in the store and the hot light through the doors caused a confusing picture. There were people running, harsh words, and a lot of shouting. Papa set down a kerosene lamp he was inspecting on the counter and run to the door. I followed with the counterman behind me.

At first, out on the boardwalk, in the bright sunlight, I couldnt see the faces on the street. I heard Petes voice before I saw him.

It wasnt me. I didnt touch her, Pete screamed. Lord, let me go.

I would of backed off from what I saw, but by then we was crowded up against the rail. First time in my life I saw the white folks and the colored folks together in a crowd.

It scared me. There was no more frown on the face of the white counterman that was beside of me. His lips were set in a smile. Hate was in his eyes. Across the street, in front of the barbershop, I saw three colored men frozen in place. The white folks surrounding them had red, twisted faces.

They were screaming. I had done nothing, but I felt them screaming at me.

Kill the nigger boy, kill the nigger. They cant be messing with our white women.

Six men had Pete by the arms. The toes of his boots dragged in the dust. His face looked up to the sky as he screamed, I didnt touch her.

I knew Pete and knew that was so. I shouted, Pete, Ill tell

My fathers hand clamped over my mouth. His other arm crushed the air right out of my chest. I read his eyes and then he slowly let me go without saying a word. I knew it wasnt so, though. The Rileys cook had heard the whole thing; she just kept on working in the kitchen and watched Betty Jo and her father. She was right there, but they didnt even notice she was alive.