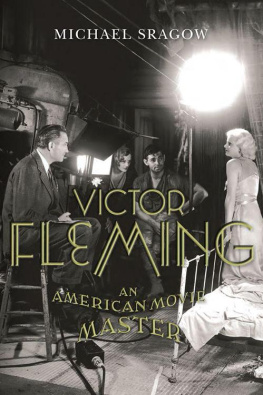

Clarence Brown

CLARENCE

BROWN

Hollywoods

Forgotten

Master

Gwenda Young

Foreword by Kevin Brownlow

Due to variations in the technical specifications of different electronic reading devices, some elements of this ebook may not appear as they do in the print edition. Readers are encouraged to experiment with user settings for optimum results.

Copyright 2018 by The University Press of Kentucky

Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth,

serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University.

All rights reserved.

Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky

663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008

www.kentuckypress.com

Unless otherwise noted, photographs are from the authors collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Young, Gwenda, author. | Brownlow, Kevin, writer of introduction.

Title: Clarence Brown : Hollywoods forgotten master / Gwenda Young ; foreword by Kevin Brownlow.

Description: Lexington, Kentucky : The University Press of Kentucky, [2018] | Series: Screen classics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014280| ISBN 9780813175959 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780813175966 (pdf) | ISBN 9780813175973 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Brown, Clarence, 18901987. | Motion picture producers and directorsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC PN1998.3.B7599 Y68 2018 | DDC 791.43023/3092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014280

This book is printed on acid-free paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Member of the Association of University Presses

To Kevin Brownlow, my esteemed mentor, adviser, and dear friend.

I hope Ive done justice to your favorite director.

Contents

Foreword

I was an enthusiastic film collector when young (still am). Sixty years ago my collecting had just progressed from the home-movie gauge of 9.5mm to 16mm, a semiprofessional gauge introduced in 1925. By the 1950s, hundreds of silent films had been transferred to 16mm, but the popularity of television soon led the majority of film libraries to close down.

When a film library in Coventry sent me a list of available films, I was amused by a title with a very un-Hollywood ring: The Goose Woman (1925). Who would want a film with a title like that? I thought. These lists gave little away. They sometimes mentioned the starif it was Chaplinbut seldom the cast, let alone the director. I considered passing up The Goose Woman but then decided to take a risk. The price was a bit steep, but the list did mention a remarkable all-star cast that included Louise Dresser as the goose woman, Mary Pickfords brother Jack as her son, and Constance Bennett as his fiance.

With ex-library prints, one was invariably heartbroken by the ripped footage and badly duped picture quality. But the moment I switched on the projector, I was overwhelmed with delight. For one thing, the print had been taken from the camera negativethe quality was almost stereoscopicand it had been tinted and toned in the style of the original. The script had been adapted from a story by Rex Beach, a surefire source for remarkable early films such as The Spoilers (1914) and Winds of Chance (1925).

I sensed that this film would be an exception to the rules of silent-era Hollywood, and so it proved. Imagine an American release from the glamourobsessed Golden Age that showed the squalid living conditions of a crazy old woman, a former opera star. Made in a period when mother love was sacrosanct, this mother accuses her son of ruining her voice (she insists she lost it when giving birth to him). When he retaliates by blaming her drinking, she says, via a title, How dare you call me a drunkard? and slaps him hard across the face.

Brilliantly acted and superbly photographed, the film was directed in a style both subtle and striking. When Id finished watching it, there seemed no book I could turn to for information about the film or the filmmaker. I felt that if there were any more American silents as good as this one, Id happily devote my life to finding them.

I decided to write a fan letter to Clarence Brown and sent it in care of the Screen Directors Guild in Hollywood. While this tactic had worked before, I received no reply. (One could only dream of receiving a response.)

A week later, the telephone rang; it was Thomas Quinn Curtiss, theater critic of the Paris-based New York Herald-Tribune. I hear you have found The Goose Woman, he said. He asked me to bring it to his suite at the Savoy Hotel, which I did, and we ran it on the wall. He was most impressed and declared that Brown had just arrived in Paris on his annual visit to the Motor Show. Curtiss was obviously testing me on Browns behalf. Having proved the films existence, I received a date to meet the great man.

I hauled my heavy 16mm projector to Paris, only to discover, to my embarrassment, that it would not work on the French electrical system. I appealed to Henri Langlois, head of the French Cinmathque, who agreed that we could watch the film in his theater at Trocadero the following morning. When we arrived, however, we had to wait. The theater was occupied by Roger Vadim, Brigitte Bardots director and ex-husband. When he finally emerged, I thought Vadim would be thrilled to meet Greta Garbos director, but he simply shook hands with Brown and departed.

There was no musical accompaniment, which was a pity because the silence led Brown to talk through his film, something I would never have encouraged, as I felt it shattered the mood. Of course, he provided fascinating information; for instance, the picture was based on the real-life Hall-Mills murder case, which had never been solved because the chief prosecution witness, a woman who looked after pigs, kept changing her story.

At one point, a long tracking shot showed the goose woman (and her pet goose) walking along a path in the open countrythis was now the heart of Westwood, California, home of UCLA. Brown himself played the murder victim toward the end; he accepted walk-on parts long before Hitchcock.

When the film was over, Brown turned to me with a satisfied grin. I didnt know I was that good, he said.

Brown may have been a remarkably sensitive director, but he came across as a typical American businessmanat first glance, youd take him for an oil tycoon. But he was generous; he asked me to lunch at the exclusive Hotel George V, although when he saw my tape recorder, he said he didnt want me to use it. (He must have thought I was from Confidential magazine.) I was determined to get a proper interviewas a tribute to his achievements, it was the least I could do. So I ate with one hand while the other held the microphone beneath the tablecloth.

He was quite brusque and unemotional at first, but I realized he was protecting himself from becoming

Next page