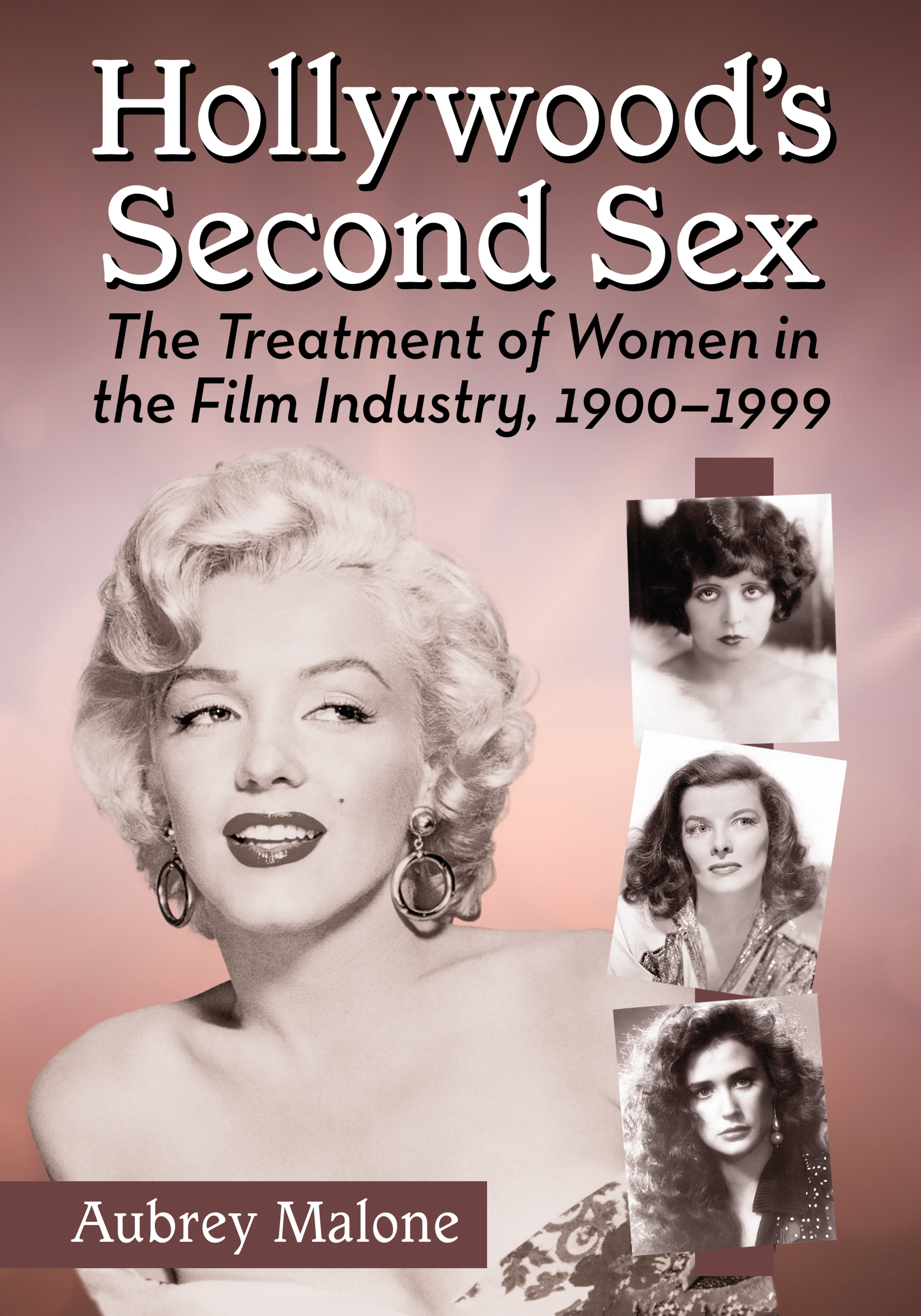

Also by AUBREY MALONE

The Defiant One: A Biography of Tony Curtis (McFarland, 2013)

Censoring Hollywood: Sex and Violence in Film and on the Cutting Room Floor (McFarland, 2011)

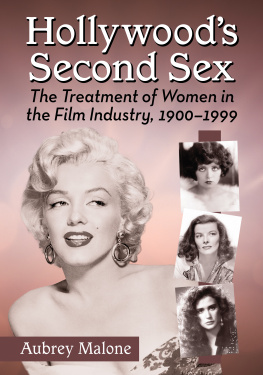

Hollywoods Second Sex

The Treatment of Women in the Film Industry, 19001999

Aubrey Malone

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1951-4

2015 Aubrey Malone. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

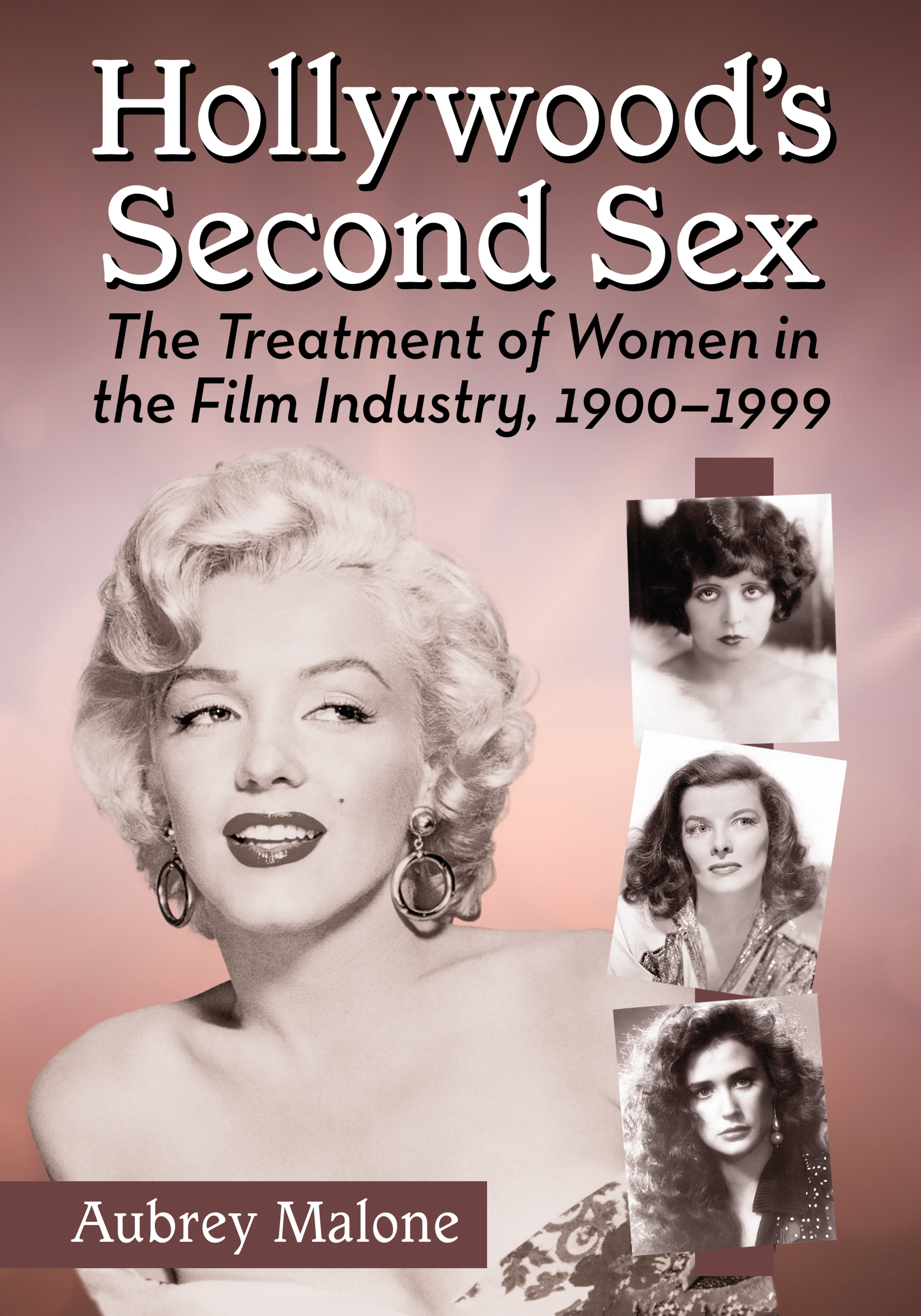

On the cover: Marilyn Monroe, 1954 (Photofest); Clara Bow, Katharine Hepburn, Demi Moore (authors collection)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

A book of this brevity can hardly hold pretensions of comprehensiveness. All it can do is give selective (and, one hopes, representative) examples of a mindset extant in the front offices of the studios featured, and the often cruel and dismissive men within.

Ive combined an examination of the lives of a range of famous (and un-famous) actresses with an analysis of many of the films in which they appeared. The themes of these films often echo the tragedy and victimization of some of their lives. They are a sober reminder of a business that plucked people from obscurity and later cavalierly thrust them back into obscurity (or toward an even worse fate) when their time was up.

Introduction

Hollywood, said Mamie Van Doren, is a haunted town, full of ghosts and memories. A lot of blond bombshells and platinum goddesses didnt make it. They died long before the wrinkles and lines they lived in fear of had a chance to appear in their beautiful faces. There were also those who made it and then lost it, for any number of reasonsthe cruelty of the moguls, the streamlining of their careers, personal involvements with men who didnt have their best interests at heart, or an industry that wasnt quite ready for them.

In our progressive era, we might think that Hollywoods war on women is over. But this is far from the case. Women in the Hollywood film industry might endure less sexual harassment than in years past, but has much really changed about who holds the reins of power or what kinds of films are being made? Pauline Kael once speculated that the history of American movies could be encapsulated in a marquee poster she once saw with the words Kiss Kiss, Bang Bang. This book explores that theory.

We begin with silent screen vamp Theda Bara, a woman seen as evil by the pioneers of cinema because she peddled sex. The Bara Syndrome, if we may call it that, continued with noir movies, which generally portrayed women as rotten to the core. In contrast, so-called womens pictures placed them on pedestals. But, as Betty Grable liked to joke, a man only puts a woman on a pedestal to get a better look at her legs. Or did men put them there simply to get them out of the way?

To succeed as an actress, Ethel Barrymore observed, a woman had to have the face of Venus, the brain of Minerva, the memory of Macaulay, the figure of Juno and the hide of a rhinoceros.

After Bara I investigate the flapper era and the promises it afforded women before being blunted by the sad plight of stars like Clara Bow and Louise Brooks, whose careers ended far too soon. After this came the foreign influx of androgynous stars like Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich. Garbo fought against the domination of MGM boss Louis B. Mayer before becoming disenchanted by Hollywoods value system, while Dietrich struggled to assert herself under the controlling influence of her Svengali, Josef von Sternberg. When Mae West arrived, she shook the paternalistic ethos of the film industry to its foundations with her lewd humor but she too fell under the sway of the male hierarchies in time, and under the diktats of a censorship system that eventually broke her, even if she joked that she made a fortune from it.

Bette Davis was a different kind of phenomenon. Like West, she came in like a lion, leaving no doubt that she was there for the long haul. She had to fight constantly against typecasting and also against mediocre roles, studio domination, and men who were intimidated by her personality. She challenged Jack Warners ownership of her in 1936 in a seminal court case challenging contractual binding. She lost it. But the very fact that she put her head over the parapet paved the way for stars like Olivia de Havilland, who challenged the system with more success in later years.

This book is also concerned with those who failed to make their mark on movies for one reason or another. Chief among these, perhaps, was Frances Farmer, who paid the ultimate price for her headstrong personality when she was sent to a psychiatric institution. Not long after, Judy Garland began showing the strain of being a child star catapulted into the public consciousness by producers who seemed to care little for her mental health. In time Garland would become addicted to diet pills, sleeping pills and other concoctions that resulted in her premature demise.

Other victimized actresses under scrutiny in the book include Rita Hayworth, a bashful star who was both used and abused by the men in her life and also her bosses, in particular Harry Cohn, for whom she represented little but a dollar sign. Hayworth was exploited for her sexuality as well, like many of her contemporaries, including Jane Russell, an actress only slightly more famous than her breasts after The Outlaw (which exhibited these assets with some aplomb) went on release in 1943.

When America entered World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, women benefited briefly from the absence of male stars from the screen, enjoying the kind of prominence theyd sampled during the flapper era. But when Johnny came marching home again, hurrah, hurrah, the ladies were shunted back to the shadows once again and slotted into subsidiary roles as the token eye candy. Gone suddenly were performances like that of Greer Garson in Mrs. Miniver and Joan Crawford in Mildred Pierce. Instead we saw a multiplicity of jingoistic excesses that once again relegated women to the sidelines as moral support to the male.

The forties ended with the suicide of Carole Landis (after she was jettisoned by Rex Harrison) and the pillorying of Ingrid Bergman, who did nothing worse than fall in love with a man who wasnt her husband (Roberto Rossellini) and have his child. It would be seven years before she was forgiven and brought back into the Hollywood fold.

In the fifties we saw Rita Hayworth elbowed aside when she was no longer considered beautiful enough to captivate the masses. In place of this love goddess, one was invited to sample the charms of Marilyn Monroe. The fifties was also the decade of Hugh Hefner and Playboy magazine. Monroe was its first centerfold and she became as much a victim of this culture as Jayne Mansfield and Diana Dorsher alleged clonesas well as a multitude of other women Hollywood waved in audiences faces for their delectation, most of them with breasts even more alluring than those of Jane Russell.

Next page