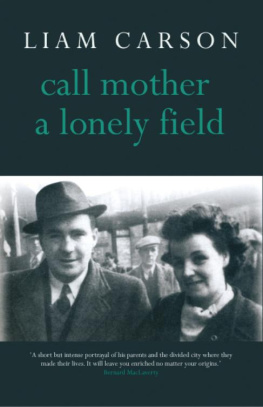

Praise for Call Mother a Lonely Field by Liam Carson

A tale from a dark and troubled placeBelfast in the 70s and 80s. Whatever light there is in the book comes from love and language. Liam Carsons Call Mother a Lonely Field is a short but intense portrayal of his parents and the divided city where they made their lives. It will leave you enriched no matter your origins.

Bernard MacLaverty

Carson presents the sights, the sounds, the smells, the essential character of the Falls Road of the period His mothers descent into Alzheimers is described with a tenderness that is almost unbearable. Every mother should have a son like thisand indeed it is a lucky child who had parents like his. Liam Carson has done them both proud in this affectionate, haunting, highly readable and, at times, poetic memoir.

Maurice Hayes, Irish Independent

In this perfect gem of a memoir Liam Carson invites us into an Irish-speaking family home that was a bastion against the evils of imperialism, both cultural and material. Liam gs story is one of setting out and return. For him, as for his father, Ithaca is not a place but a language. Like Hugo Hamiltons The Speckled People, this memoir is a must-read.

Nuala N Dhomhnaill

A unique poetic meditation on an Irish-speaking family which draws fine threads between language and history and the life-saving properties of a wide-ranging selection of narratives, including family lore, folk songs, comic books and the heroics of mythology which underpin the Irish language. Liam Carson pours an astonishingly concentrated draught of wisdom into one slim volume.

Martina Evans

Like the city he grew up in, Liam Carsons memoir of life in Belfast winds like a tangled web of streets, dreams, cultures and philosophies , where every page, pavement and street corner offer another dab of colour to a fascinating picture His description of his mothers Alzheimers disease and eventual death are blessed with clarity, gentleness and a heart-wrenching sadness. His memories of shared moments with his father are beautifully rendered Carsons greatest achievement is recycling a complex mix of emotions and ideas on language into a deeply moving read.

Michael Foley, The Sunday Times (Irish edition)

For such a tiny book, it is crammed with dozens of stories. Dreams are recounted, the plotlines of adventure books paraphrased and analysed, poems and song lyrics reprinted, folk stories and urban myths retold. This is a small book, and a hauntingly simple one. Call Mother a Lonely Field is an immensely pleasurable book, and a valuable addition to the canon of Irish autobiography.

Conor OCallaghan, The Irish Times

for Niamh and Eithne

gr go deo

And like young Irishmen in English bars

The song of home betrays us

Jackie Leven

Contents

My father would often tell me his dark dreams. In them, I am always a little boy, and we are lost in a forest. It is night, and we cannot see where we are going. I fall into quicksand, I am trapped, I am sinking. My Da frantically tries to rescue me. He stretches his hand to me, but cannot reach me. After his death, my own dark dreams came.

I see myself sitting on the Black Mountain, gazing down on the city. Immediately behind the Black Mountain rises the summit of Divis Mountain, whose name comes from the Irish dubh ais or black place. I look out to Belfast Lough and there is a massive swell building near Helens Bay. A huge wave rises, a wall of sea rising like a dragon from the depths, a tsunami that will drown the whole of Belfast. And although I am on the mountain , I can also see into the kitchen in Mooreland as if it is only a couple of feet away. My Ma and Da are sitting down to tea, oblivious to the catastrophe hurtling towards them. I run down the hillside, but I know it is too late, I know I cannot save them.

I find my dream echoed in an old scal s, or fairy tale, from Donegal, called Na Tr Thonnathe three waves. It tells of a man and his son out fishing on the open sea. It is a quiet, calm day. Then three large waves rise behind them as they head for land. The first is big, the second larger, and the third is so massive, they fear they are about to be drowned. The father asks his son to cast a knife ins an tuath. Into the tuatha word that is difficult to translate. In Dinneens dictionary, it is defined as evoking the sinister: wrongness, goety or negative magic.

The son does his fathers bidding, hurling the knife into the heart of the demonic wave. Within the blink of an eye, the wave vanishes, and the men come safely to land. That night the son is visited by a man who tells him the knife is embedded in his daughters foreheadand that he must accompany him to remove the knife. He is taken to a fairy island and warned to refuse anything he is offered. He is brought to where the girl is stretched on a bed; he removes the knife, and she arises, safe and sound. The island people offer him all manner of things, but he refuses their gifts. The man tells the son he must forsake his native land. And so he does, heading for America, never to see his father again.

For my father, Liam Mac Carrin, Irish was a place of refuge. He was once interviewed for BBC Radio Ulsters Tearmannwhere guests were asked what gave them sanctuary in their lives. He chose the Irish language itself. He hid within and took comfort from words.

He arrived into this world as William Carson on 14 April 1916, only ten days before the Easter Rising. He spent his childhood i dteach bheag i srid bheagin a little house in a little street, not far from Clonard Monastery, just off the Lower Falls Road. There was one room downstairs, two upstairs, and an outdoor toilet. His father, Davy Carson, was a fitter for Harland and Wolffbut he lost that job on 21 July 1920, when he was forced out of the shipyard in an anti-Catholic and anti-socialist pogrom.

A contemporary account tells of the fear on that day:

The gates were smashed down with sledges, the vests and shirts of those at work were torn open to see if the men were wearing any Catholic emblems, and woe betide the man who was. One man was set upon, thrown into the dock, had to swim the Musgrave channel and, having been pelted with rivets, had to swim two or three miles, to emerge in streams of blood and rush to the police officer in a nude state.

My grandfather was lucky to escape a beating or worse. In the next few days, seven Catholics and six Protestants were shot dead in the conflict that spread throughout the city. In the period between July 1920 and June 1922, over 20,000 Catholics were driven from their homes; 9,000 men were forced out of their jobs; and nearly 500 people were killed in sectarian attacks in Belfast.

Davy Carson never regained a full-time job. For years he struggled to make ends meet. He would get temporary jobs from time to timeobair chrua mhaslach, as my father described itheavy, taxing work with a spade or pick in hand, often in the cruellest of weather. But as the 1920s drew to a close, and the depression of the 1930s loomed, the building work dried up. In 1928, he teamed up with some friends; they bought ladders, cloths and buckets, and set themselves up as window cleaners. It wasnt easy to make a living at first. Most of the local women could only afford to pay a few pennies, and even the pennies were hard to come by, money was that tight for the people of the Falls. But soon he was cleaning windows for the local shopkeepers , for offices, and even the local police station.