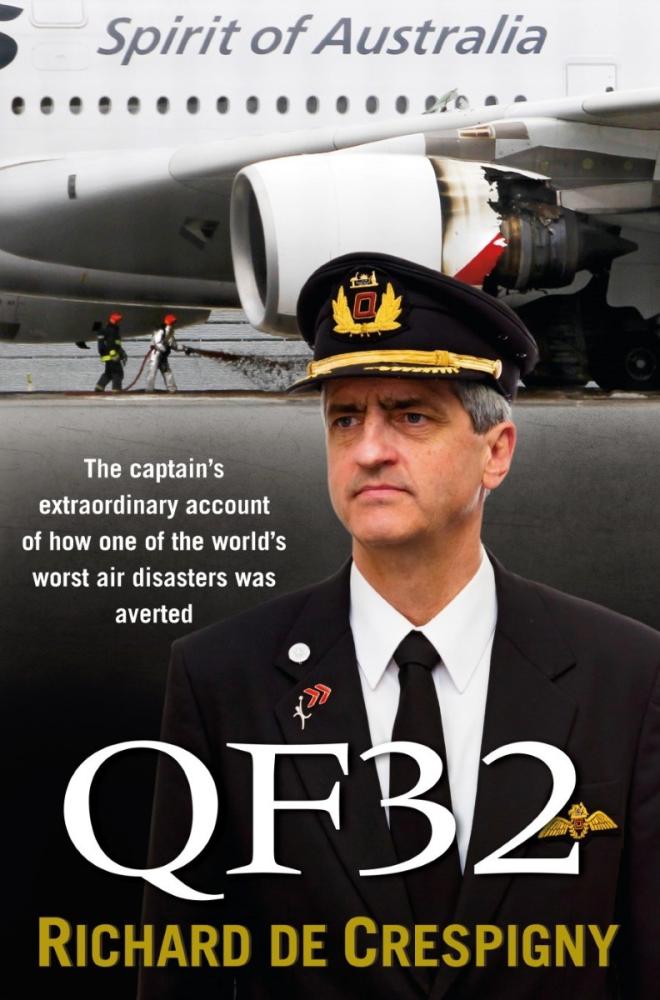

Melbourne born and educated, Richard Champion de Crespigny got his first taste of a future flying career as a fourteen year old when his father took him on a tour of the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Academy at Point Cook in Victoria.

In 1975, aged seventeen, he joined the RAAF. One year later, he started flying. During his eleven years with the RAAF, he was seconded as Aide-de-Camp to two Australian Governors-General Sir Zelman Cowen and Sir Ninian Stephen. Richard remained with the RAAF until 1986 when he joined Qantas.

Richard and his wife, Coral, have two children, Alexander and Sophia.

For more information, please visit http://QF32.Aero.

First published 2012 in Macmillan by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd

1 Market Street, Sydney 2000

Copyright Richard Champion de Crespigny 2012

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. This publication (or any part of it) may not be reproduced or transmitted, copied, stored, distributed or otherwise made available by any person or entity (including Google, Amazon or similar organisations), in any form (electronic, digital, optical, mechanical) or by any means (photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

This ebook may not include illustrations and/or photographs that may have been in the print edition.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

de Crespigny, Richard.

QF32 / Richard de Crespigny with Mark Abernethy.

9781742611174 (pbk.)

AirplanesCollision avoidance.

Aircraft accidents.

Other Authors/Contributors: Abernethy, Mark.

363.12416

Adobe eReader format: 9781743347881

EPUB format: 9781743347898

Online format: 9781743347874

The author and the publisher have made every effort to contact copyright holders for material used in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked should contact the publisher.

Typeset by in Sabon 11.5/18 pt by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design by Deborah Parry Graphics

Love talking about books?

Find Pan Macmillan Australia online to read more about all our books and to buy both print and ebooks. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events.

This book is for everyone who played a role in QF32.

To all of you, I am proud of you.

Thank you.

To wonderful Coral.

You are the wind beneath my wings.

To my son, Alexander, and daughter, Sophia, who keep my feet firmly on the ground!

To Dad thank you for the RAAF Academy tour!

With thanks to Mark Abernethy,

my collaborator, who was integral

to this story being told.

Contents

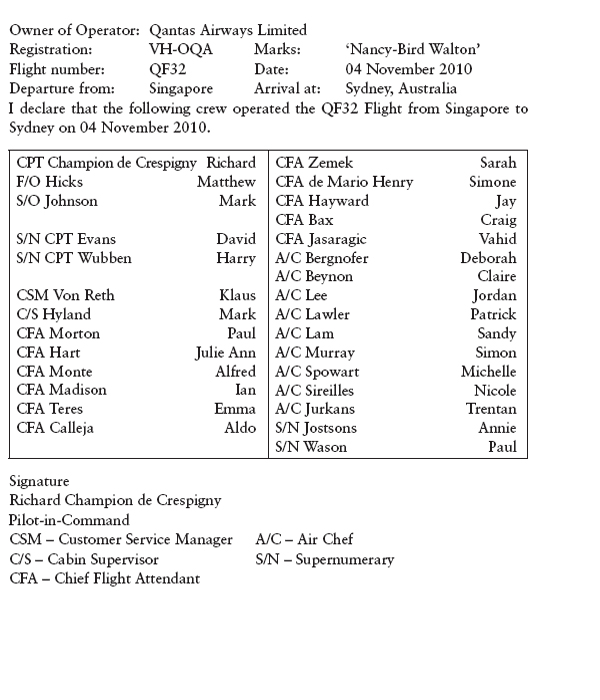

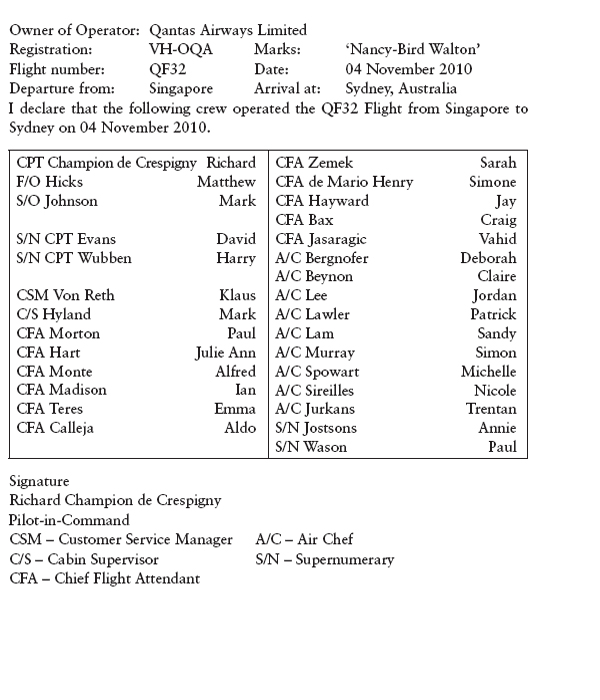

GENERAL DECLARATION

The Pilot-in-Command is responsible for completing the General Declaration. The General Declaration that I completed for QF32 is reproduced below. This document is necessary for international flights, and includes details of the crew, aircraft registration and itinerary. Copies are provided for airport authorities and customs at the departure and destination airports.

CHAPTER 1

First Flight

February 1976. It was a rare day over southern Victoria, with the sky so clear you could look upwards and see blue receding forever into white. I remember it well because I was at the controls of a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) A-85 Winjeel and beside me, in the instructors seat, was a legend of the Air Force, Flight Lieutenant Bill Evans.

It is the mark of a small air force that the best of the best are called on to teach the novices, and so Evans was spending time away from flying Mirage III fighters to instruct new RAAF trainee pilots in the propeller-driven Winjeel. An aircraft first designed in 1949, the Winjeel was a bit like a Caterpillar D6 bulldozer with wings it didnt look like it belonged in the air.

The nine-cylinder, 13-litre Pratt & Whitney radial engine produced a deafening roar as we chugged away from the Point Cook Air Force Base to our cruising altitude of 5000 feet. The heavy Winjeels performance was not helped by the fact its tail fin had been moved significantly forward along the airframe for the sole purpose of making the aircraft less stable and easier to flick into a violent spin.

Trimming the aircraft to fly hands-off at cruise altitude and heading across the Bellarine Peninsula aiming for Tasmania, I was happy the engine had lost its coughing roar and found its comfort level, more like a sleeping alsatian than an angry attacking bear. This was my first instructional flight and it seemed pretty straightforward. Responding to Evanss tour of the flight controls and his instructions to feel the stick in my hands and the rudder pedals at my feet, I gave the thumbs-up.

I relaxed as we settled in, cruising at around 140 knots. The sky seemed to sparkle with sugar crystals and the green of Victoria gleamed like a jewel. It was a beautiful day to fly, a great day to be alive. As I was starting to enjoy myself, Evanss voice crackled in my ears: Throttle back let her slow down, hold your height and give her some left rudder.

I eased the throttle back. As the speed slowed I felt the stick pull forward as the heavy nose wanted to drop. I pulled back to maintain the altitude, pushed slightly on the left rudder pedal to twist or yaw the aircraft to the left, then put a bit of right stick to stop the aircraft rolling left wing down.

Back off some more, Evans said, and give me some more left rudder.

I did as I was told, feeling the big engine in front of me quietening. Even at full throttle the old Pratt & Whitney radials only turn at around 3000 RPM, and backing off the throttle at 5000 feet sounded like the whole engine was about to shut down. The Winjeel didnt just look like something that shouldnt fly, it also felt like it, and I worried that too much pulling back on the throttle would put us into a stall. As the speed slowed I had to pull back harder, and adding rudder meant I needed even more right stick to stop the aircraft rolling left.

We must have slowed to about 70 knots by the time Bill Evanss voice jumped into my headset again. Take more off the throttle and give it more rudder!

Less throttle, more rudder, more back stick, more crossed aileron input suddenly the Winjeel flipped right wing over the left. The nose dived for the ground it must have looked like the footage you see of aircraft breaking away from a formation, except we were flying at about 60 knots and corkscrewing straight down to the ground in a tight spiral.

Every one of my senses was in overload. I remember my mouth hung open in a mask of terror as the aeroplane spun downwards with continuous roll, yaw and pitch forces I had never felt before. I knew the theory of an aircraft spinning, but never imagined it to be so physically stressful. Sitting on my parachute and held in tight by my harness, I turned towards the fighter ace for guidance.

Flight Lieutenant Bill Evans was sitting back, looking at me with a smile on his face and his arms crossed smugly over his chest. He winked and pointed at me: here I was frozen with terror and the instructor wasnt going to help! It was my plane. I turned back to face the fast-approaching farmlands and gripped my hands around the joystick.