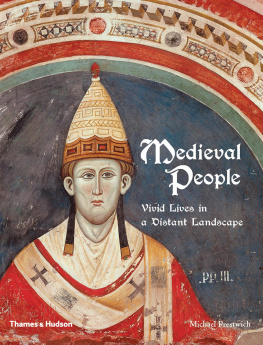

Frontispiece: Dante Alighieri, in a painting by Domenico di Michelino of 1465. The poet expounds his Divine Comedy, one of the greatest works of medieval literature. Behind him, there is an image of purgatory. Hell is to the left, and Paradise to the right.

About the Author

Michael Prestwich is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Durham. Among his many books are Knight (Thames & Hudson, 2010), Plantagenet England, 12251360, Armies and Warfare in the Middle Ages and English Politics in the Thirteenth Century.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Renaissance People

The Medieval World Complete

The Medieval World at War

Power and Profit:

The Merchant in Medieval Europe

Knight:

The Medieval Warriors (Unofficial) Manual

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

For my grandchildren,

Ben, Joshua, Hannah, James, Oliver and Alexander.

1.

An Age of Empires

2.

An Age of Confidence

3.

An Age of Maturity

4.

An Age of Plague

5.

An Age of Transition

The term medieval has many different implications. It can suggest a romantic world of knights and ladies, of courtly love and heroic deeds of arms. It is often thought of as referring to an age of faith, one of religious certainties. It is also used as a term of abuse, with implications of ignorance and brutality. This is not surprising, for the medieval period was many things. It was an age of change as much as of continuity, as empires rose and fell, and old concepts were challenged by new ideas.

The Psalter world map, created in England in about 1265, has East at the top and Jerusalem at the centre. British Library, Add. 28681, f. 9.

When did the Middle Ages begin? There can be no definitive answer to this question. For some commentators, it was with the decline of the Roman Empire, while for others that was the start not of the medieval period, but of the Dark Ages. It could, then, be argued that the Middle Ages did not begin until the eleventh century, or even later. For Petrarch, writing in the fourteenth century, a dark age was ushered in by the fall of Rome which continued until his own day. This book commences in the eighth century with the reign of Charlemagne; his establishment of a new empire in western Europe in 800 marked a fundamental moment of change.

There is less argument about the close of the Middle Ages, although one suggestion is that it occurred at any point between the thirteenth and the twentieth centuries, according to taste. There is broad agreement, however, that it can be placed around 1500. The fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, the invention of printing in the mid-fifteenth century, the discovery of the New World in 1492, and the French invasion of Italy in 149495, have all been seen as crucial, as has the papal condemnation of Luther in 1520.

Many of the popular characterizations of the Middle Ages have little validity. Much that is often thought of as medieval was nothing of the sort. People in the Middle Ages did not believe that the earth was flat. Torture was far less common than in subsequent centuries. While there was of course much superstition in the Middle Ages, accusations of witchcraft were rare; it was the early modern period that saw large-scale witch-hunts. Medieval warfare involved hard hand-to-hand fighting, but the Thirty Years War in the seventeenth century saw much more brutality than the Hundred Years War of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Medieval scholars may have considered alchemy a valid science, but so did Isaac Newton. Nor was the Middle Ages lacking in innovations. The list of technological advances includes mechanical clocks, guns, printing, blast furnaces, spectacles, stirrups and the compass. While it is easy to dispel at least some of the myths about the period, there are no obvious overarching generalizations to replace them. My hope, however, is that this book will provide an indication of the richness and complexity of the centuries from 800 to 1500.

Detail from the Catalan Atlas of 1375, showing Marco Polo, with his father and his uncle, travelling on the Silk Road through Asia to the Far East. Bibliothque nationale de France, Ms. Es. 30, Morel-Fatio 119, Pl. V.

The focus of this book is largely on Europe and the Mediterranean world, but it extends into Asia with the Mongol conquests under Chinggis Khan in the thirteenth century, which opened up routes to the Far East, as Marco Polos journeys show. In intellectual terms, it is not possible to understand the Middle Ages without appreciating the immense importance of the work of such Muslim scholars as the Persian Ibn Sn, with his achievements in medicine and philosophy. It was through the world of Arab scholarship that much Classical learning was transmitted to western Europe.

Many of those in this book, notably emperors, popes and kings, have been selected for their undoubted importance. In Ibn Sn and Thomas Aquinas there are great philosophers. Distinguished soldiers discussed included El Cid and John Hawkwood. Among the writers of history, Matthew Paris and Jean Froissart were particularly notable. I have included others, such as the Venetian nuns of the convent of SantAngelo, because their careers illustrate particular facets of the age, though they themselves may have had relatively little influence on the course of events. Some individuals close to the bottom of the social spectrum, such as the French peasant leader Guillaume Cale, also feature. Many careers spanned different fields. Benedetto Zaccaria was both merchant and admiral. The artist Piero della Francesca was a mathematician of distinction. Richard of Wallingford was an abbot, a clockmaker and a leper. With scholars, authors and artists my aim is not to provide detailed analysis of their ideas and works, but to describe their lives and the challenges they faced.

The quality of the sources about particular individuals has been important in making my choice. There would have been no point in examining the career of a solitary hermit living by the banks of the river Wear, Godric of Finchale, had his life not been written about at considerable length. Autobiographies were uncommon in the Middle Ages, but Guibert de Nogent wrote an intriguing account of an appalling childhood, while Pedro IV of Aragon and Charles IV of Bohemia were responsible for autobiographical chronicles. The Arab nobleman Usma ibn Munqidh also wrote a fascinating memoir.

The medieval world may have been male dominated, but not to such an extent that women could not make their mark. They could be important in many ways: this book shows them as queens, in Eleanor of Aquitaines case of both France and England; as authors, with the remarkable history written by Anna Komnene; and as military commanders, with Matilda of Tuscany and Joan of Arc. They could also be spiritual leaders. One notable visionary was Hildegard of Bingen, whose interests extended from music to herbal medicine. In many ways, the women in this book are more remarkable than the men, given the difficulties they faced in making their voices heard.

Next page

![Timothy May - The Mongol Empire [2 Volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia](/uploads/posts/book/143064/thumbs/timothy-may-the-mongol-empire-2-volumes-a.jpg)