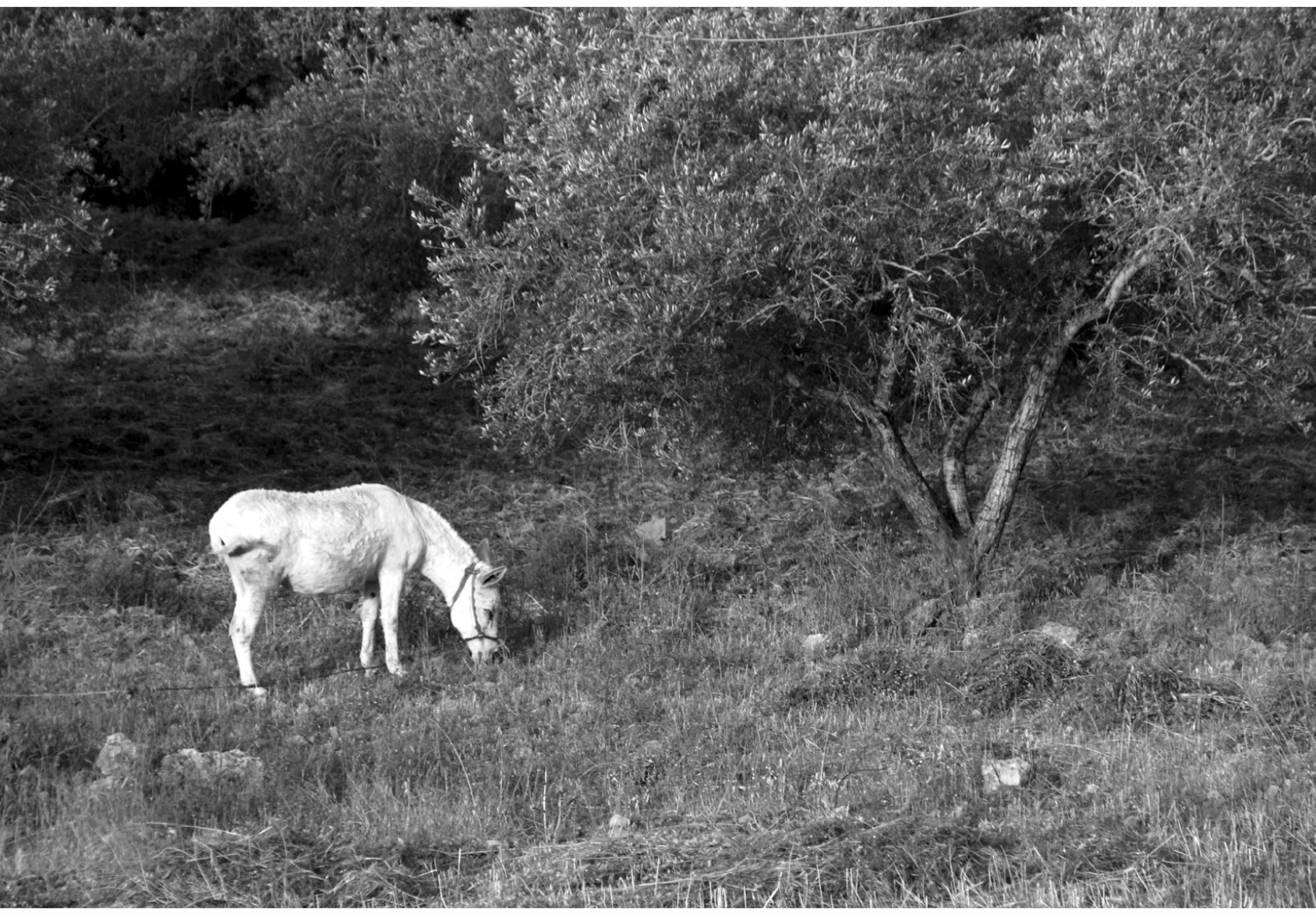

Donkey grazing in an olive grove near Ramallah, April 2017.

INTRODUCTION

COMMON LIVES

I wish I was a donkey, said the great Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish in a television interview in 1997, pointing to a scrawny donkey standing under an olive tree near the Palestinian town of Ramallah. A peaceful, wise animal that pretends to be stupid. Yet he is patient, and smarter than we are in the cool and calm manner he watches on as history unfolds. But in the history-laden and often heartbroken land between the Mediterranean Sea and the Jordan Rivernow the state of Israel and occupied Palestinedoes the donkey watch so placidly as humans go their troubled way?

I do not think so. In this book, I explore the histories and intertwined fates of some of the large mammals that live in this fractured landhyenas, goats, camels, sheep, gazelles, wild boars, ibexes, jackals, and donkeys, along with a pack of wolves, a solitary leopard, and several herds of cows, real and imagined. I encounter both wild and working animals along the way, as well as those animalssheep, goats, cowswhich we generically and tellingly call livestock. Almost all, with the exception of a European breed of cow, have inhabited this land under all its human names for millennia, contributing to our very survival. The current threats to their lives and well-being differ, but all are our companions in conflict.

What do their lives and our long engagement with these animals, whether in fear and aggression, through dominion and domestication, or with empathy and affection, tell us about the unfolding of the history of Palestinians and Israelis and the future of our common land? What do the stories, poems, and folktales we weave around these animals tell us about ourselves?

As one of the inhabitants of this land, I am part of the story I am telling. I came to Ramallah in 1982 to work for a year at Birzeit University on human rights issues, and I have remained for more than three decades and perhaps for a lifetime. Palestine has offered me a challenging working life, whether sitting in military courtrooms with inspiring Israeli and Palestinian lawyers defending university students and staff, participating with colleagues and friends on campus in founding an Institute of Womens Studies, or traveling to Madrid in 1991 as a writer for the Palestine delegation to the Madrid Peace Conference, a moment of hope.

But two particular measures of these crucial decades have led me to think about the lives of animals other than humans in this fragile land: times of walking and times of war.

I often walk and wander (when wars will allow it), usually with my partner, Raja Shehadeh, both before and after our marriage in 1988 (walking, by the way, is conducive to courting). Our town of Ramallah rests on the hills of the central highlandsthe spine that runs through the West Bank, a rather recent name for land west of the Jordan River. The terraced hills host olive groves and fruit trees, as well as wilder terrain visible as one descends through one of the numerous wadis (valleys), heading for a spring or simply a flat rock to sit on in the warm sunshine.

Some of the animals in this book are acquaintances from these walks: gazelles seen with a leap of the heart, wild boars spotted with more than a tremor of fear, sheep grazing on winter green, and goats munching on our ubiquitous thorns in the heat of summer. In spring, donkeys plow under the olive trees and in autumn carry away the harvest. Mahmoud Darwishs donkey is even nearer, a neighbor down the street. Other walks have taken me farther: to the long wadis that cut through the Jerusalem wilderness and to the dramatic canyons above the Dead Sea. I have been fortunate as well to take walks in the Galilee, but for almost two decades I have not been able to enter Gaza, as I do not belong to one of the proper bureaucratic categories able to secure a permit to enter the other part of occupied Palestine: diplomats, staff of international organizations, foreign journalists, and occasional businessmen.

Over the years, I have experienced the changes visited upon the animal habitats in the occupied West Bank and beyond. Whether fleet gazelles or plodding donkeys, these animals went their own way amid the media fanfare that accompanied both the 1993 signing of the Declaration of Principles between Israel and The Palestine Liberation Organization on the White House lawn and the Interim Agreement two years later. They could not hide, though, from the ensuing dramatic changesnot only political but also physicalin the landscape that is their home. Those agreements, often termed the Oslo Accords or simply Oslo, mandated a transitional period where certain civil responsibilities over the Palestinian population in the occupied West Bank and Gaza were transferred to a newly created Palestinian Authority, pending final status negotiations. A quarter of a century later, negotiations are frozen and the transitional arrangements have become what many call occupation by another name. (And indeed, the Israeli military government was never dissolved.)

The West Bank was and still is fragmented into zones governed by an impersonal alphabet. Area A, where the Palestinian Authority has full control (more in theory than in practice), constitutes only 18 percent of the West Bank (excluding Jerusalem) and is a patchwork of unconnected urban centers and a scattering of villages. Area B, where Palestinian security personnel can only operate with Israeli permission, contains the majority of Palestinian villages, frequently not including all of any given villages agricultural and grazing land. The most unfortunate Palestinian communities, as well as most of the lands wildlife, lie in Area C, the 61 percent of the West Bank under sole Israeli control and the location of more than one hundred Israeli settlements. Here, I explore what this complex period has meant not only for those of us who walk and cherish the land but for the lives of wild and working animals and the humans who depend on them.

My second measure of time is war and conflict: Raja and I once counted the wars since our wedding, celebrated at the height of the First Palestinian Intifada, a mass civil anti-occupation uprising that began in December 1987. At first we decided wars came neatly in twos: two intifadas (the second of which erupted in 2000, wracked with violence and despair), two Gulf Wars (in 1990 and 2003), two Gaza Wars, and two major wars between Israel and Lebanon (the first back in 1982, the last in 2006). But then we looked around us at regional conflagrations and promptly lost count. The losses of human lives and livelihoods can be tallied by statisticians and mourned by citizens, but it is time, I think, to reflect as well on the massive destruction visited on our animal companions and the environment that sustains us all.