I love movies. Studio movies, indie movies, black-and-white movies, animated movies, subtitled moviesI love them all. And growing up with the first generation of VCRs and video rental stores, I could revisit my favorites again and again. Nowadays, this is something we all take for granted, but back in the mid-1980s movies on demand was a new and utterly amazing experience. For the first time in motion-picture history, viewers could watch movies in their own homes, on their own schedules, and on their own terms.

As teenagers, we studied our favorite films with manic intensity, pausing the tapes to parse lines of dialogue, study the architecture of a starship, or note a weird directorial signature. We rewound A New Hope to watch that one clumsy stormtrooper bumping his head on the ceiling. We read the credits in search of familiar names. We laughed over the perverted Easter eggs hidden in animated Disney films.

If you grew up watching movies in the late 1970s or early 1980s, you probably did many of these things, too. It was the advent of the summer blockbuster. All the tools of the great cinematic mastersKurosawa, Hitchcock, Lang, Bergmanwere being applied to something new, fresh, and fun, to movies tailor-made for the children of baby boomers. We were an audience of millions, with hungry imaginations, time on our hands, and allowance money burning holes in our pockets. We were raised on Star Wars and Indiana Jones and we wanted moremore aliens, more monsters, more strange worlds to explore. But if we couldnt have more movies, wed settle for the same movie again and again. Wed line up on opening weekends for the sequels to Back to the Future, Ghostbusters, and Star Trek.

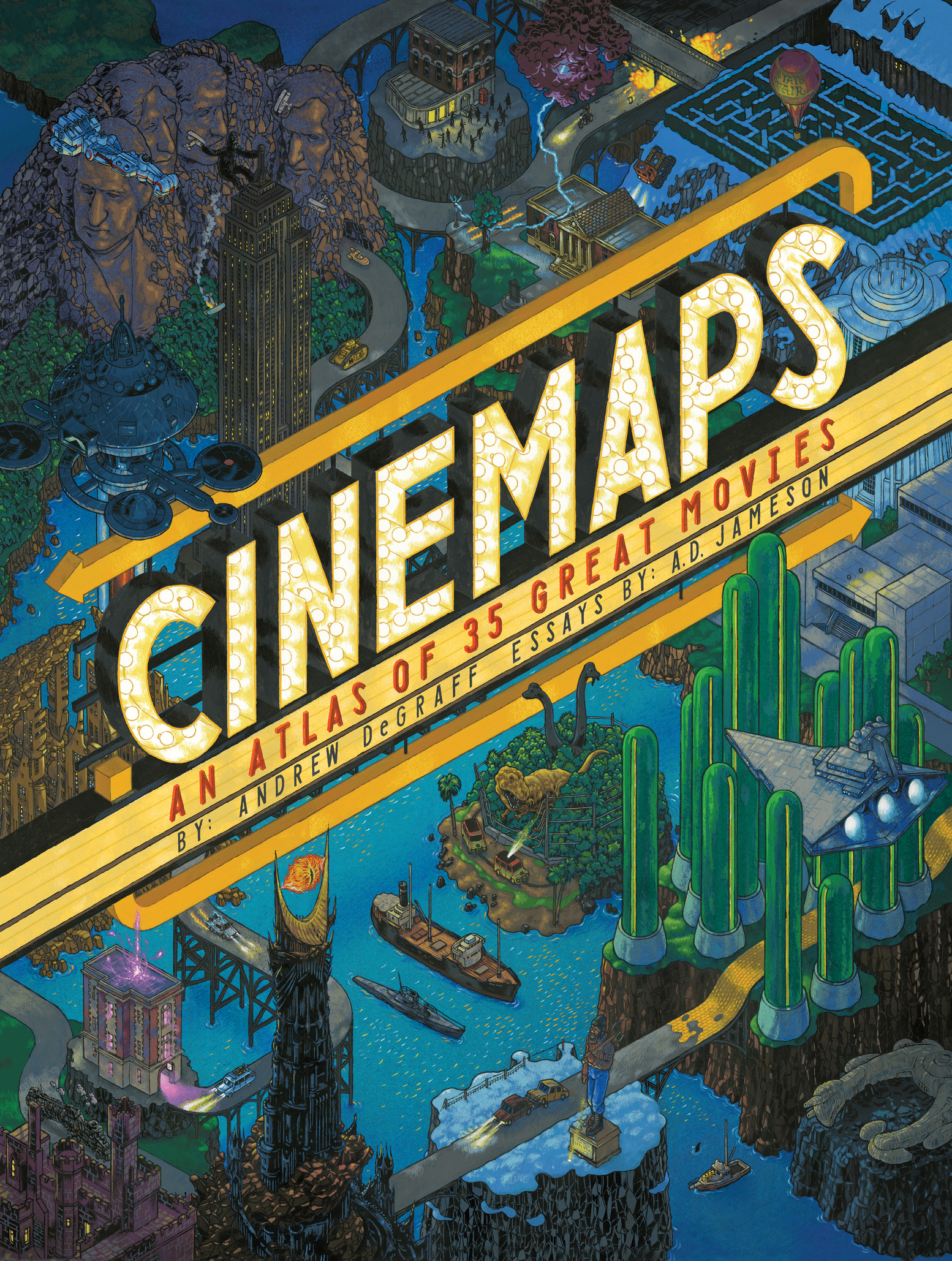

These films were marvels of craftsmanship created by extraordinary talents. Our monsters were created by H. R. Giger and Jim Henson. Our locations and sets were designed by Syd Mead, Ron Cobb, and Ralph McQuarrie. Our comedy, by directors like John Hughes and Rob Reiner, was deftly insightful and, later, beautifully manicured by the likes of Edgar Wright and Wes Anderson. Our adventures were designed and dressed by Jim Steranko. Our posters were painted by Drew Struzan and John Alvin. As a child, I didnt realize how lucky I was. Now I do, and I suppose this book is the evidence. The illustrators, designers, painters, and creators mentioned above were some of my earliest influences, even if I didnt yet know their names. This book and its paintings are in many ways an homage to all the talented people working behind the scenes of my favorite films. Before I knew what I wanted to be, I knew I wanted to be them.

So as I gleefully kneel at the altar of popular cinema, you might be wondering why Ive left such strange offerings.

In other words, why did I paint all of these maps?

The answer probably lies somewhere in my childhood. As a kid, I covered my bedroom walls with full-color maps pulled from the pages of my fathers National Geographic collection. I had a comforter listing all the states and their capitals; you could say I was effectively swaddled in maps every night. I was fascinated by the way maps blend information with graphic design. Id trace my finger over rivers and roads, imagining the people who lived in these strange and far-flung places.

Jump cut to twenty years later: I was working as a freelance illustrator when a travel magazine asked me to create some maps. It was an irresistible opportunity, but I quickly learned that creating a map is a lot harder than reading one. To make a good map, I had to really know my subject, wrangling a laundry list of different things into some sort of order. If youve ever hand-painted a sign and found yourself running out of room for the last word, then you have an inkling of the mapmakers dilemma. Planning ahead is essential. Geography and spacing are generally going to hinder, not help, you. But I enjoyed the challenge, and more map assignments started coming my way.

Camp Firewood (2011), 22 22 in (56 56 cm). Gouache on paper.

Then one day it occurred to me that I might marry my two childhood interestsmaps and movieson the same page. My first effort was drawing the underground caverns of Richard Donners The Goonies; I followed up with the summer camp setting of David Wains Wet Hot American Summer (). Neither was as detailed as the maps in this book; there were no character arrows and the approach was pretty stark, just one color of gouache and zero people. But they were sprinkled with little Easter eggs from the films, like Troys bucket (from The Goonies) and the bale of hay roadblock (from Wet Hot American Summer). To my delight, people really responded to these paintings. They recognized the settings and mentally filled in the restthe story and the quotes and the characters they knew so well. Soon they began requesting more.

After those maps came North by Northwest, with its Saul Bassinspired use of arrows for one character, and then Star Wars and Indiana Jones, with arrows following all the major players. Then Shaun of the Dead, Star Trek, Back to the Future, The Shining, The Lord of the Rings, and others. I think of these paintings as scale models of summer blockbusters, diagramming a limited amount of timeusually about 120 minutesbetween the opening and closing credits. As viewers and fans, weve traveled every inch of these journeys before. Weve trekked through the forest and the jungles, weve soared past the planets and the space stations. Yet we keep returning to these worlds again and again. With these maps, we can view our favorite films from a fresh perspective. We can travel the familiar journeys in new and unfamiliar ways.

The mapmaking process is long and laborious. Each one takes several weeks, even months, to complete; my map for the Lord of the Rings trilogy was the most complex of all, requiring more than 1,000 hours. When Im working on a new map, Ill watch the corresponding film at least twenty times, occasionally as many as fifty times. For weeks, the film Im mapping will be a constant backdrop to my life. The soundtrack will invade my dreams. Ill spend a lot of time researching locations through set photography, production notes, and some of the insanely detailed LEGO models posted by fans online (I cant believe these exist, but they do).

Sometimes Ill even research locations that are never completely shown in the film. Whenever possible, I like to reveal the full extent of a place, like the Soldiers and Sailor memorial in Pittsburgh, which houses significant scenes in