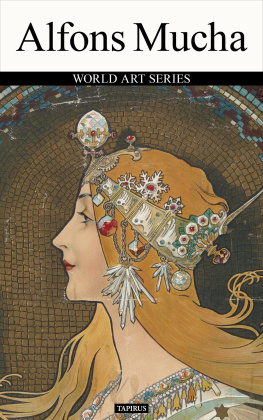

Author(s):

Patrick Bade and Victoria Charles

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bade, Patrick, author.

[Mucha (1860-1939)]

Alphonse Mucha / Patrick Bade [author] and Victoria Charles [editor].

pages cm

"Revised and enhanced edition. Patrick Bade and Jean Lahor, authors"--Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Mucha, Alphonse, 1860-1939. I. Lahor, Jean, 1840-1909, author. II. Charles, Victoria, editor. III. Title.

N6834.5.M8B33 2013

709.2--dc23

2013033094

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-040-8

Patrick Bade and Victoria Charles

Alphonse

Mucha

Contents

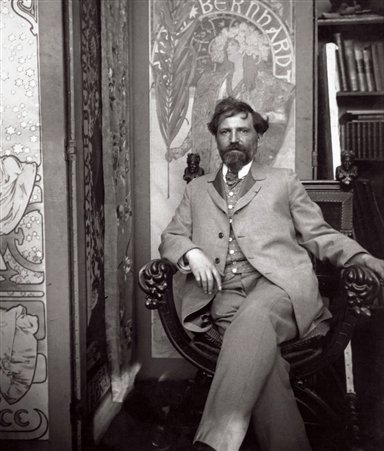

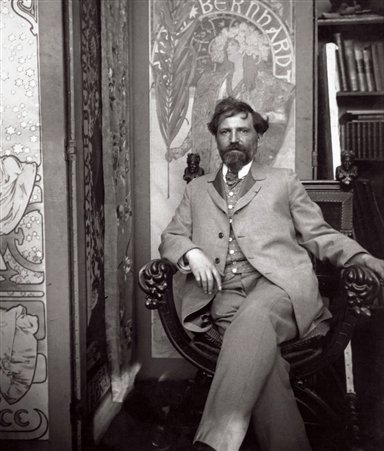

Mucha in his studio,

rue du Val-de-Grce, Paris, c. 1898.

ART NOUVEAU

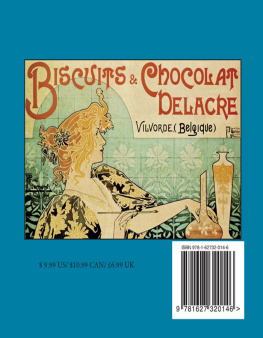

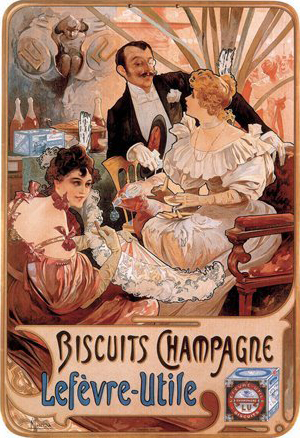

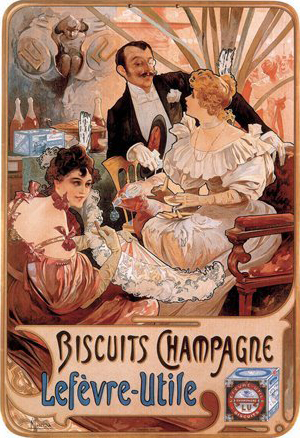

Biscuits Champagne Lefvre-Utile, 1896.

Colour lithograph, 52.1 x 35.2 cm .

The Mucha Trust Collection.

The Origins of Art Nouveau

One can argue the merits and the future of the new decorative art movement, but there is no denying it currently reigns triumphant over all Europe and in every English-speaking country outside Europe; all it needs now is management, and this is up to men of taste. (Jean Lahor, Paris 1901)

Art Nouveau sprang from a major movement in the decorative arts that first appeared in Western Europe in 1892, but its birth was not quite as spontaneous as is commonly believed. Decorative ornament and furniture underwent many changes between the waning of the Empire style around 1815 and the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution. For example, there were distinct revivals of Restoration, Louis-Philippe, and Napoleon III furnishings still on display at the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris. Tradition (or rather imitation) played too large a role in the creation of these different period styles for a single trend to emerge and assume a unique mantle. Nevertheless, there were some artists during this period that sought to distinguish themselves from their predecessors by expressing their own decorative ideal.

What then did the new decorative art movement stand for in 1900? In France, as elsewhere, it meant that people were tired of the usual repetitive forms and methods, the same old decorative clichs and banalities, the eternal imitation of furniture from the reigns of monarchs named Louis (Louis XIII to XVI), and furniture from the Renaissance and Gothic periods. It meant designers finally asserted the art of their own time as their own. Up until 1789 (the end of the Ancien Rgime), style had advanced by reign; this era wanted its own style. And (at least outside of France) there was a yearning for something more: to no longer be slaves to foreign fashion, taste, and art. It was an urge inherent in the eras awakening nationalism, as each country tried to assert independence in literature and in art.

In short, there was a push everywhere towards a new art that was neither a servile copy of the past nor an imitation of foreign taste.

There was also a real need to recreate decorative art, simply because there had been none since the turn of the century. In each preceding era, decorative art had not merely existed; it had flourished gloriously. In the past, everything from peoples clothing and weapons, right down to the slightest domestic object from andirons, bellows, and chimney backs, to a drinking cup were duly decorated: each object had its own ornamentation and finishing touches, its own elegance and beauty. But the 19 th century had concerned itself with little other than function; ornament, finishing touches, elegance, and beauty were superfluous. At once both grand and miserable, the 19 th century was as deeply divided as Pascals human soul. The century that ended so lamentably in brutal disdain for justice among peoples had opened in complete indifference to decorative beauty and elegance, maintaining for the greater part of one hundred years a singular paralysis when it came to aesthetic feeling and taste.

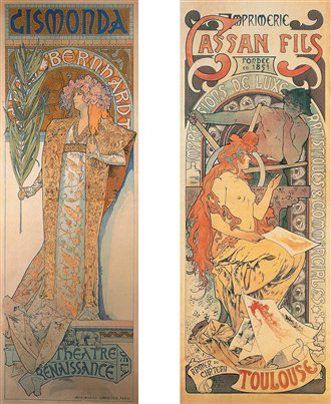

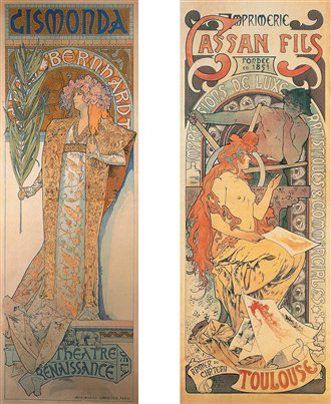

Gismonda, 1894.

Colour lithograph, 216 x 74.2 cm .

Mucha Museum,Prague.

Cassan Fils (print shop), 1895.

Colour lithograph, 174.7 x 68.4 cm .

Mucha Museum, Prague .

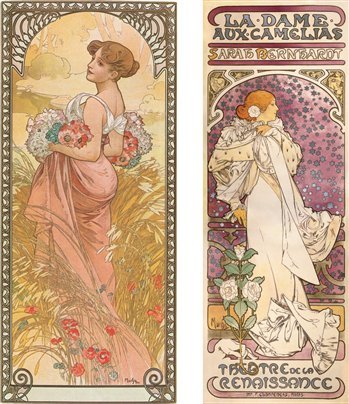

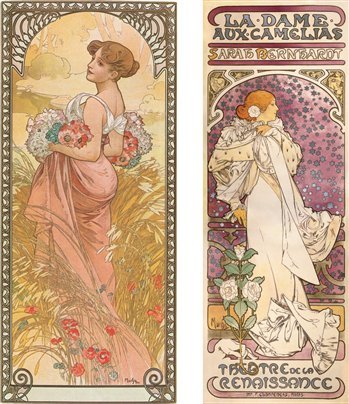

The Seasons: Summer, 1900.

Colour lithograph, 73 x cm .

The Mucha Trust Collection.

La Dame aux camlias, 1896.

Colour lithograph, 207.3 x 72.5 cm .

The Mucha Trust Collection.

The return of once-abolished aesthetic feeling and taste also helped bring about Art Nouveau. France had come to see through the absurdity of the situation and was demanding imagination from its stucco and fine plaster artists, its decorators, furniture makers, and even architects, asking all these artists to show some creativity and fantasy, a little novelty and authenticity. And so there arose new decoration in response to the new needs of new generations.

The definitive trends capable of producing a new art would not materialise until the 1889 Universal Exposition. There the English asserted their own taste in furniture; American silversmiths Graham and Augustus Tiffany applied new ornament to items produced by their workshops; and Louis Comfort Tiffany revolutionised the art of stained glass with his glassmaking. An elite corps of French artists and manufacturers exhibited works that likewise showed noticeable progress: Emile Gall sent furniture of his own design and decoration, as well as coloured glass vases in which he obtained brilliant effects through firing; Clment Massier, Albert Dammouse, and Auguste Delaherche exhibited flamb stoneware in new forms and colours; and Henri Vever, Boucheron and Lucien Falize exhibited silver and jewellery that showed new refinements. The trend in ornamentation was so advanced that Falize even showed everyday silverware decorated with embossed kitchen herbs.

The examples offered by the 1889 Universal Exposition quickly bore fruit; everything was culminating into a decorative revolution. Free from the prejudice of high art, artists sought new forms of expression. In 1891 the French Societ Nationale des Beaux-Arts established a decorative arts division which, although negligible in its first year, was significant by the Salon of 1892, when works in pewter by Jules Desbois, Alexandre Charpentier, and Jean Baffier were exhibited for the first time. And the Socit des Artistes Franais, initially resistant to decorative art, was forced to allow the inclusion of a special section devoted to decorative art objects in the Salon of 1895.