All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher and copyright holders.

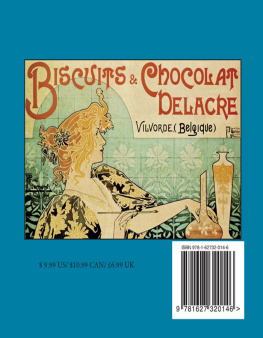

All notations of errors or omissions (author inquiries, permissions) concerning the content of this book should be addressed to . The Publisher believes the use of the poster images at the size depicted qualifes as fair use under United States copyright law.

INTRODUCTION

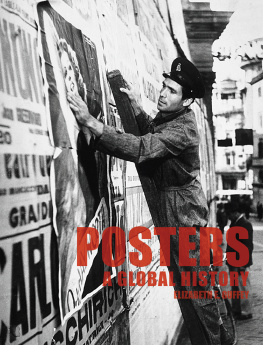

T he poster has been around for hundreds of years, serving first and foremost as a means of communication. The simplest definition of a poster is any form of paper with a printed design or text that is created to be hung on a vertical surface. The posters genesis was purely a textual form, most often used for displaying government decrees. One of the earliest, more developed forms of poster was a means of advertisement, such as for one of Shakespeares plays. Eventually, posters came to be used as a way to spread propaganda, especially during wartime. Another common use of posters is as a cheap and efficient way to mass-produce popular artworks for the general publics consumption.

As the printing process became more modernized and streamlined, posters began to include images in addition to text. With the invention of color printing, the poster slowly evolved until its focus was primarily the visual image rather than the text, because an image could relay the desired message more quickly. The purpose of the poster image was to catch the eye of the passerby so that he or she would look more closely at the text for more detailed information.

The tremendous success of the poster can be attributed to one man, Alois Senefelder, and his groundbreaking invention, lithography. Alois Senefelder (1771 to 1834) was a German playwright and actor. He soon discovered that he preferred writing plays more than performing them. But when he began to fall into debt to his local printer, he began to experiment with new, non-commercial forms of printing.

Senefelder found that he could apply chemicals to a block of fine-grained stone, such as limestone (Germany is renowned for its Solnhofen limestone, which is especially fine-grained and thus ideal for retaining fine details), and the chemicals would literally etch the image or text he had created onto the stone. After wetting the etched stone, he could roll grease-based ink over it. The etched areas of the stone (i.e., the desired image) retained the ink, while the un-etched, or negative, areas repelled it. Paper could then be laid down on the inked limestone block, put through a press, and the inked image would be transferred to the paper.

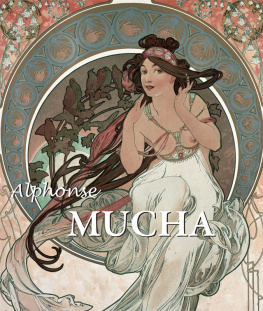

The limestone block could be re-used countless times to print the image. When the printer wanted to change the image, all he needed to do was to sand down the etched layer and re-start the process on the limestone block. Thus, Senefelder discovered the first planographic printing process (i.e., printing from a flat surface as opposed to a raised or incised surface) that was put to commercial use. Lithography not only allowed easy mass-production of posters for commercial reasons, but also helped turn the poster into an accepted and popular form of art. Lithography is taught in art schools today as its own art form. Some of the most well-known artists to utilize the poster as an art form are Henri Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha.

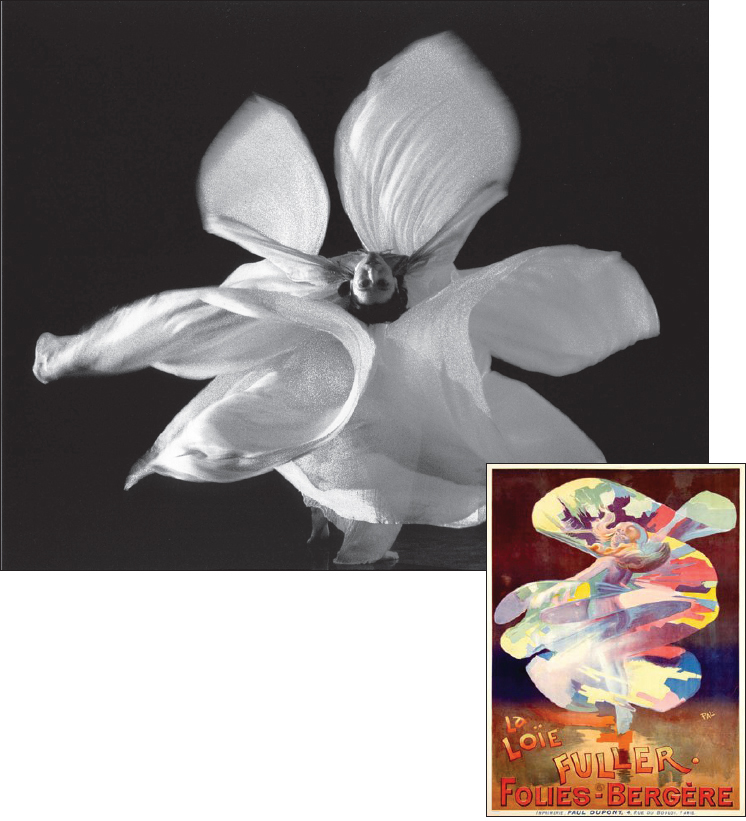

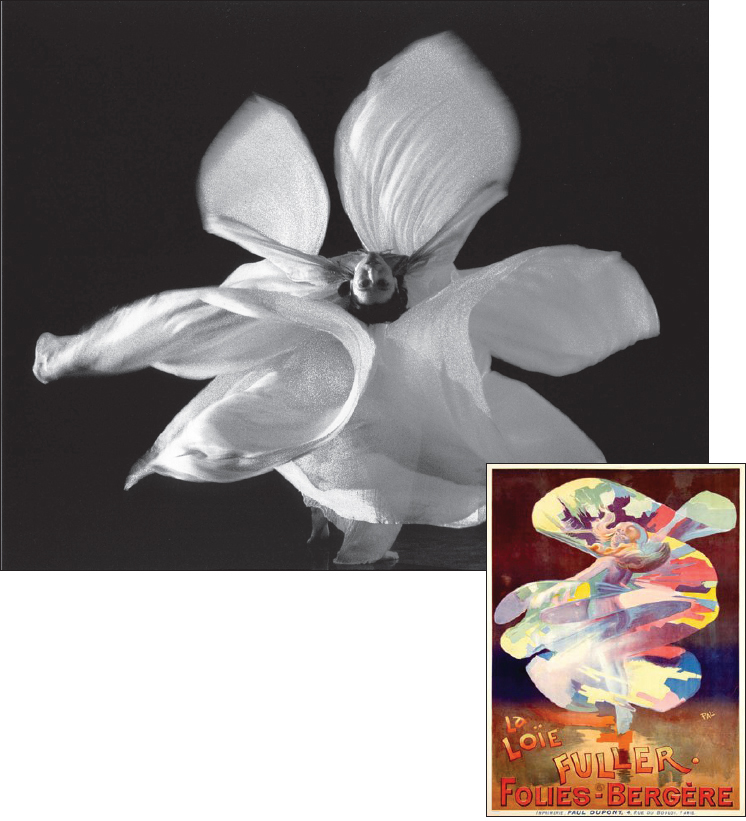

The American dancer Loe Fuller performing her infamous Serpentine Dance (above) and an artistic rendering of the same by Jean de Paleologu (1855-1942) to promote Fullers appearance at the Folies Bergre nightclub in Paris.

Henri Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa (1864 to 1901), more often referred to simply as Toulouse-Lautrec, was an artist primarily based in Paris during the late 19th century. He was born to a French aristocratic family and spent a good part of his childhood drawing and sketching. Throughout his life he was plagued by an undefined congenital health problem, which many have attributed to a family history of inbreeding. From a young age, he suffered from brittle bones that never fully healed after they broke, and as he aged, these malformed bones inhibited his natural growth and resulted in his unusually short stature. Although his torso was a normal adult size, his legs never grew longer than their length when he was 13 years old.

Toulouse-Lautrecs physical handicaps effectively pushed him to pursue artistic studies because he was unable to participate in most other activities. Thanks to his familys aristocratic influence, he was able to study under the guidance of the prominent French painter Lon Bonnat. Toulouse-Lautrec eventually found his niche in Montmarte, the bustling Bohemian neighborhood in Paris. Writers, artists, and philosophers from every walk of life and from all corners of the world co-mingled there in the mid- to late-19th century, influencing each others creative process and inspiring new, modern, freer forms of expression.

Some of Toulouse-Lautrecs first subjects were the prostitutes of Montmarte, which would lead to his later, very famous paintings and posters of Paris dance hall girls. His early style is somewhat reminiscent of the Dutch artist Vincent van Gogh, with whom he was acquainted. As the years passed, Toulouse-Lautrecs images became more abstract representations of the women of Montmarte. Toulouse-Lautrecs first official contract for creating poster art was for Moulin Rouge, a cabaret in Pigalle near Montmarte that was topped with a red windmill. Toulouse-Lautrecs attention-grabbing posters that depicted the cabarets dancing girls doing the wildly suggestive cancan, and especially of the cabarets star performer Jane Avril, made Moulin Rouge one of the most well-known cabarets in all of history.

Moulin Rouge, 1900

Alphonse Mucha (1860 to 1939) is another artist well known for his artwork that graced countless posters at the turn of the 20th century. Mucha was born in what is now the Czech Republic. Since a young child, Mucha had exhibited artistic talent. After graduating from high school, he collaborated with his brother and a friend to form a decorative painting business, primarily murals for public buildings. He also worked for a few years in Vienna, Austria, for a theatrical design company. Mucha continued to freelance and was soon hired by Count Karl Khuen who requested that Mucha decorate his castle with murals. Muchas work pleased the count so much that he offered to pay for him to attend the Munich Academy of Fine Arts so that he could receive formal training.

After graduating from the academy, Mucha moved to Paris. To support himself, he worked for a printing company. He was luckily in the right place at the right time one day in 1894, when he was the only artist in the office and was tasked with designing a poster for Sarah Bernhardt, the most famous actress in all of Europe. Muchas poster depicts an image of Bernhardt in the role of Gismonda, her name encircling and framing her face. The poster was produced using lithography, as were most during this period, and attracted much attention due to its beauty and uniqueness. Bernhardt was so impressed by Muchas work and the success his work brought her that she offered him a long-term contract. Muchas posters of Bernhardt led to his fame, and his unique artistic style is what initially began the Art Nouveau movement. In addition to the Bernhardt posters, Mucha began to receive a flood of other commissions, ranging from magazine ads to menus, postcards, and calendars.