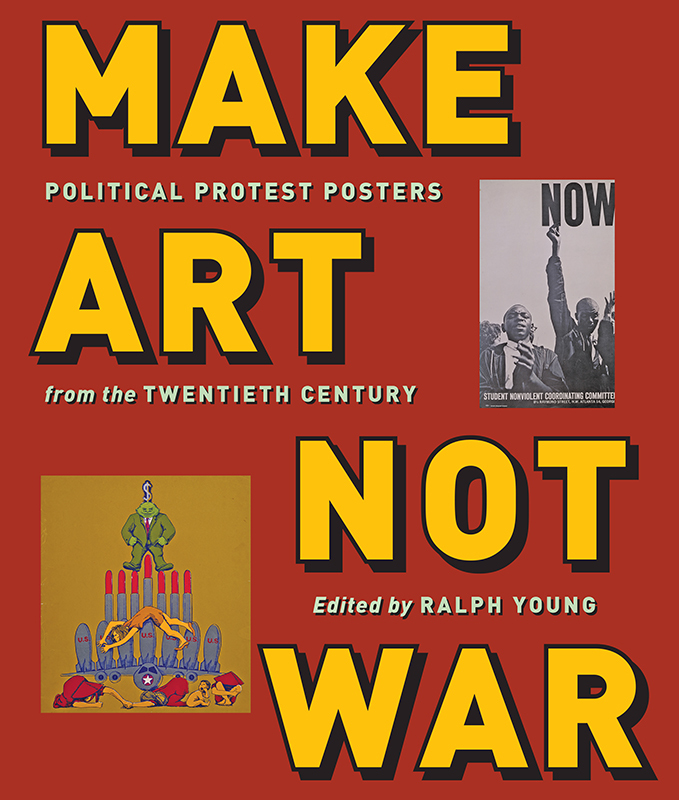

Make Art Not War

Make Art Not War

Political Protest Posters from the Twentieth Century

Edited by Ralph Young

Washington Mews Books

An imprint of

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York

Washington Mews Books

An imprint of

NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS

New York

www.nyupress.org

2016 by New York University

All rights reserved

References to Internet websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor New York University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

ISBN: 978-1-4798-1367-4

For Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data, please contact the Library of Congress.

New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. We strive to use environmentally responsible suppliers and materials to the greatest extent possible in publishing our books.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Also available as an ebook

To the memory of my mother and father,

Emily Mildred House Young

Ralph Eric Young

Contents

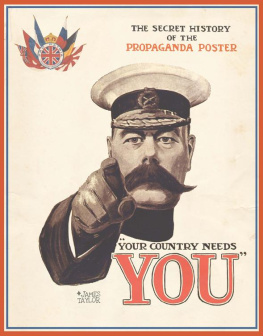

Two of the most recognizable images of twentieth-century art are the most famous painting by that most famous of twentieth-century artists, Pablo Picassos Guernica, and the rather-modest mass-produced poster by an unassuming illustrator, Lorraine Schneider, War is not healthy for children and other living things. From Picassos masterpiece to a humble piece of poster art, artists have used their talents to express dissent, to protest against injustice and oppression, to reveal publicly to the world their strong objection to the actions of the powerful. Visual art, whether high art or posters, broadsides or fliers, cartoons or comic books, murals or graffiti has been used effectively by dissenters to push for change, to protest inequality and discrimination, in a high-minded effort to bring about a better world. Visual art is one of the many valuable tools by which protestors have expressed and promoted their dissenting points of view.

The United States is a product of dissent. Religious dissenters, unable to worship according to their own lights, left England, the Netherlands, Rhineland/Palatinate, Scotland, and Ulster to plant colonies in the New World. By the mid-eighteenth century, political dissenters took their protests against what they perceived as a tyrannical government in London so far as to fight a war for independence that culminated in the creation of the United States of America. And they conspicuously inserted the right to dissent in the First Amendment of the nations founding document.

Americans have taken that right seriously ever since. Whenever the power structure seemed to be overstepping its bounds or whenever people felt the government was not fulfilling its duty to protect everyones natural rights, Americans have dissented. And they have expressed their discontent in a wide variety of ways: writing letters, broadsides, and polemics; preaching sermons and delivering speeches; conducting protest marches in the streets; or engaging in acts of civil disobedience. Dissenters have used literature, poetry, music, dance, comedy, cinema, theater, street theater, and puppetry to castigate the establishment. Whether it was women fighting for the right to vote or abolitionists seeking to destroy slavery or pacifists protesting against World War I or workers demanding the right to organize or beatniks and hippies denouncing middle-class mainstream values, dissenters employed every method imaginable to condemn policies and actions that they deemed unacceptable in a democracy. From Abigail Adams to Alice Paul, from Frederick Douglass to John Brown, from Eugene V. Debs to Martin Luther King Jr., from Mark Twain to Allen Ginsberg, from Joe Hill to Phil Ochs, from H. L. Mencken to Lenny Bruce, Americans have done their best to change the status quo.

We have seen how successful demonstrations and acts of civil disobedience have been in accomplishing at least some of the dissenters goals. One thinks of suffragists picketing the White House until the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and civil rights activists marching from Selma to Montgomery, which led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965, or the Stonewall Riots that kicked off the gay rights movement. In many protests, music has been especially effective in getting the message out to masses of people. The protest music of the 1960s, benefiting from technological advances in radio, television, and the recording industry, got civil rights and antiwar messages out to millions of Americans who had previously been indifferent to the African American struggle for equality and the escalation of the Vietnam War. And the legacy of singers like Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan has had an enormous influence on dissent movements ever since. Along with protest music, visual artists too have used their talents to support dissenting views. Political cartoons, comic books, graffiti, murals, posters, photography, and high art have all been productively used, with varying yet frequent success, in voicing discontent.

In the colonial period, the primary pictorial devices furthering contrarian views were broadsides and cartoons. As defiance against Londons taxation policies and steadily increasing arbitrary rule in the aftermath of the French and Indian War, groups such as the Sons of Liberty posted broadsides in public places denouncing the Stamp Act, the Tea Act, the Intolerable Acts, and other decrees and laws enacted by Parliament. Many of these broadsides were informational, raising public awareness of a regulation that was going to impose hardship on the colonists, but most of them were nothing short of propaganda, with bold-printed exclamatory headlines, for the sole purpose of inflaming public opinion in order to gain adherents to the patriot cause. Samuel Adams, one of the leaders of the Sons of Liberty, had fine-tuned propaganda into an art that became the forerunner of the protest posters of the twentieth century. One of Adamss comrades in the Sons of Liberty was the celebrated printer/engraver Paul Revere. Revere used his talents to print engravings protesting Londons policies. His most famous engraving was the volatile image he produced of the Boston Massacre, transforming the unruly, menacing mob into peaceful middle-class citizens out for a stroll and depicting the redcoats who were guarding the customs house as malicious, murderous scoundrels.

Political cartoons were also an influential method of expressing dissent in the buildup to the American Revolution. Cartoonists in the colonies and in Britain who supported the colonists grievances were withering in their sarcastic caricatures of the king and his Tory ministers. America was usually depicted as a virtuous young woman and Parliament as would-be (or actual) ravishers trying to destroy the virtue of honorable colonists.

By the nineteenth century, political cartoons published in newspapers and periodicals were the favorite means of expressing dissenting views. Whether taking on the imperial presidency of Andrew Jackson or denouncing slaveholders or free-soilers or Irish immigrants or the war hawks leading the country into the War of 1812 or the southerners pushing for a war with Mexico in the 1840s, political cartoons had a considerable impact on shaping public opinion. The artists sketching their cartoons and caricatures used humor and sarcasm, poignancy and moral outrage to express their anti-status-quo views. As is frequently the case with political cartoons, they often overstepped the bounds of propriety. One thinks of the many nativist, anti-immigrant cartoons that were published in the aftermath of the Irish potato famine, depicting Irish immigrants as sideshow freaks or unintelligent beasts.

Next page