CONTENTS

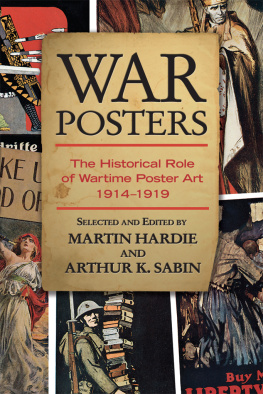

THE POSTER WAR

The Great War (191418) was the first truly modern conflict, fought on a global and industrial scale. It required the complete mobilisation of the countries involved, resulting in unparalleled state intervention into the lives of ordinary people, from conscription to the employment of women, food rationing and the gradual imposition of restrictions affecting many aspects of daily life. Communicating these changes effectively, while maintaining public morale, was recognised by all warring nations as an essential element in securing military victory. In an age before the Internet, television or radio, posters emerged as the ideal medium for mass communication, seized upon by governments, private organisations, charities and even retailers to get their war messages across to the widest possible audience. In this respect, posters were especially suited to the task at hand as they could be cheaply produced in very large numbers and distributed in a range of sizes to maximise potential display opportunities.

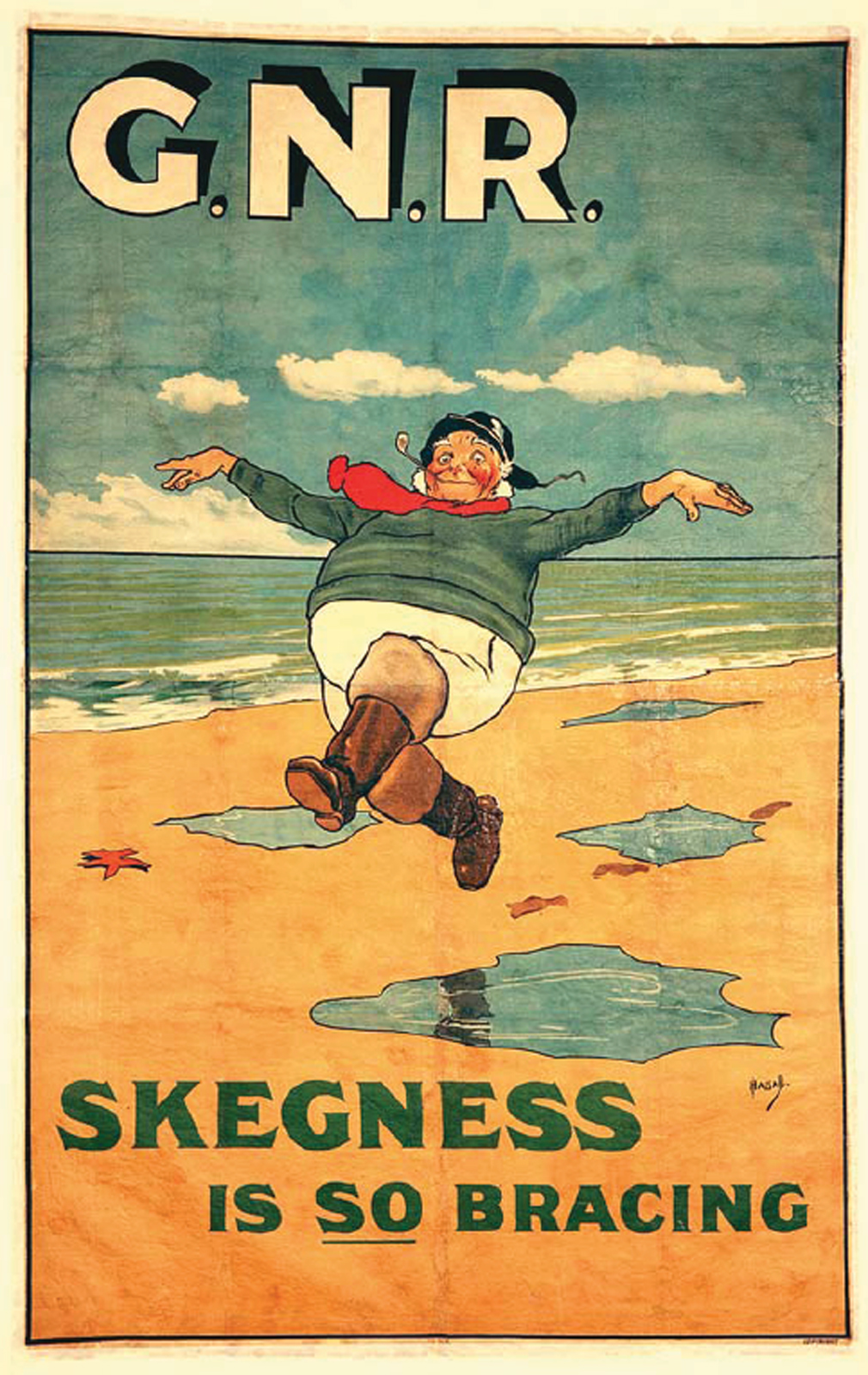

At the outset of the war in August 1914, the poster was already a mature advertising tool, which had developed over centuries from crude letterpress notices to sophisticated full-colour lithographs. Continental posters, in particular, had established a reputation for considerable artistic merit, pioneered by the likes of Jules Chret, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Alphonse Mucha during the late nineteenth century. In Britain commercial artists, including Dudley Hardy and the poster king, John Hassall, popularised a distinctive domestic approach, typified by the use of bold flat colour, a central (often comic) figure and a short direct slogan (see Skegness is SO Bracing). Together with the fledgling advertising industry, and supported by the patronage of leading retailers, manufacturers, theatres and transport companies, such artists helped to create a visual language for the poster which dominated the hoardings in the years before the war and was well understood by consumers.

John Hassalls famous railway poster promoting the bracing qualities of Skegness (1908). The vivid use of colour and a short emphasised message ( SO Bracing) was to prove influential on the design of wartime recruiting posters.

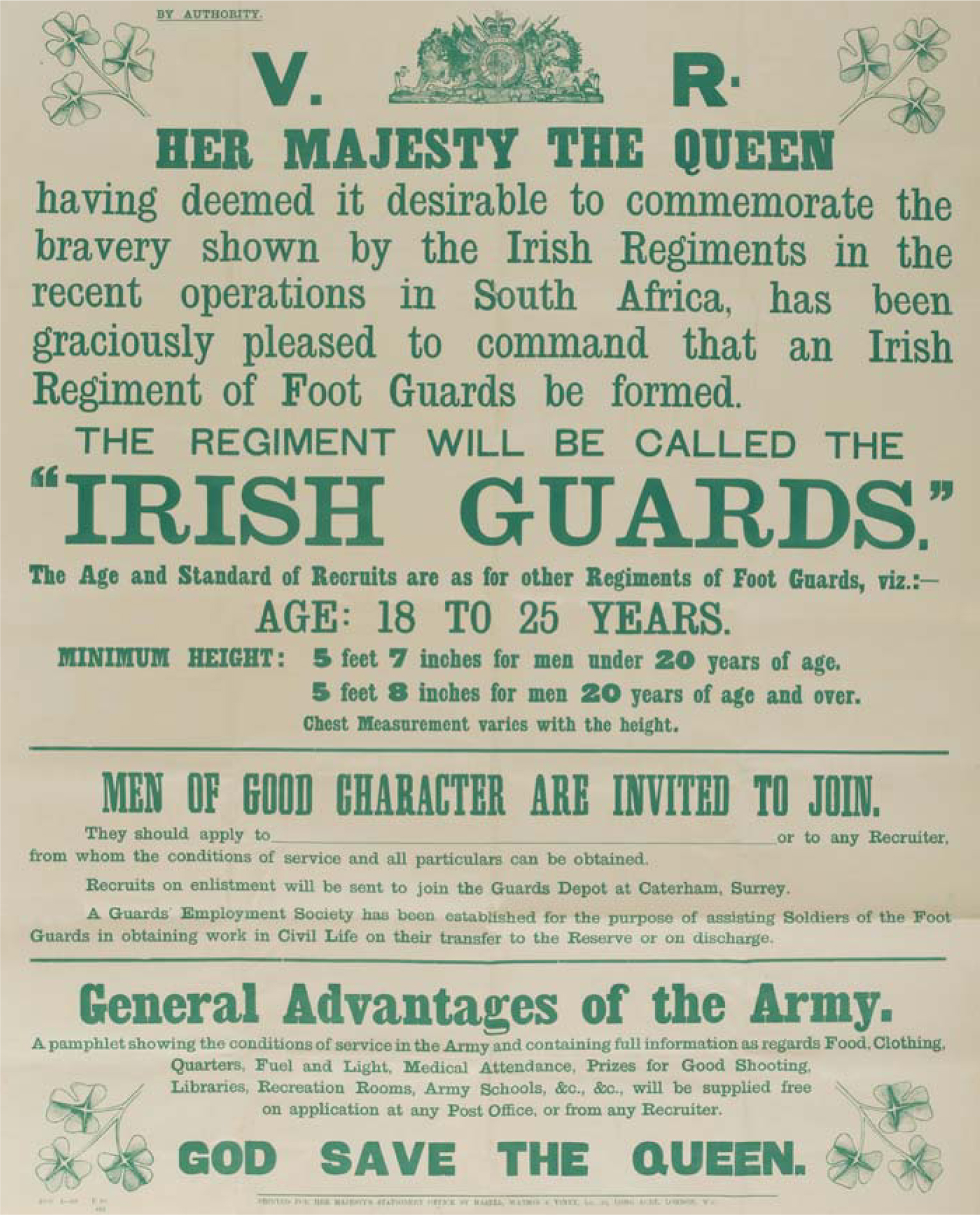

A typical pre-First World War British Army recruiting poster, in this case announcing the formation of the Irish Guards (1900) for service in the Boer War. Information about the terms and conditions of service is printed below the royal monogram of Queen Victoria, indicating that this is an official government notice.

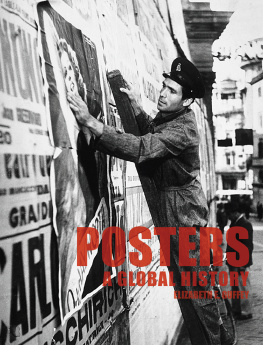

The pre-war display of posters in Europe and the United States was subject to varying degrees of regulation, although advertising was regarded as a defining, and often unwelcome, characteristic of most urban environments. Posters could be seen everywhere: in the streets, at the railway station, on the sides of buses and trams, in shop windows almost anywhere, in fact, where people congregated. Government notices, however, were usually easy to distinguish from the mass of pictorial commercial posters that jostled for the attention of the passer-by. Official proclamations and injunctions were often printed in text-only format, headed by the royal arms or some other symbol of the state.

This was to change during the war, as governments across Europe appropriated the design values, and display space, of commercial advertising. New venues were found for war posters in banks, schools, churches, libraries, factories, offices and rural settings. At first, the sheer number of war-related posters threatened to swamp available sites, a situation eventually eased by the introduction of printing restrictions caused by paper shortages. As an indication of the scale of production, the British Museum renounced its pre-war right to a copy of every poster printed in the United Kingdom for reference purposes. Luckily other institutions, most notably the Imperial War Museum in London, set about collecting representative samples from the combatant nations, resulting in the survival of thousands of individual designs.

Taken as a whole, these surviving posters provide a remarkable visual history of the war, with similar themes recurring on both sides of the conflict, underlining the need for all governments to secure the consent of their citizens through persuasion and propaganda. Posters, of course, were not the only method of communication available, and should be viewed alongside the wide variety of official and non-official channels of information, including newspapers, publications, films, plays, songs, cartoons and public meetings. Neither were all, or indeed most, wartime posters produced by government agencies alone. In fact, it is striking how many of the surviving posters were independently printed by private organisations in support of the war effort or on behalf of specific charities, thereby helping to foster a sense of shared endeavour between the government and the people.

The creation of a sense of shared endeavour, however, often masked deep-seated national tensions. In Britain, for example, the years immediately before the war had been marked by industrial unrest, an Irish crisis, suffragette militancy and constitutional difficulties, to say nothing of the growing independent spirit of the British Empires dominions. Against this background, posters were a useful tool to achieve social unity, while open dissent about the war was effectively censored under the terms of the Defence of the Realm Act (1914).

The posters featured in this publication have been primarily selected from the archives of the National Army Museum, London, with a corresponding focus on the experience of Britain and its empire during the war. Many of the themes discussed, such as the recruitment drive of 191415 and government war loans, have close parallels with the wartime poster campaigns of other nations. But there were notable differences in the United Kingdom, including the delayed introduction of conscription, a more hands-off approach by government and the existence of a highly developed advertising industry (second only to the United States), which created a uniquely British response. So, too, did Britains relationship with her imperial subjects, especially in the economically advanced dominions of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada, where posters proved to be an important tool in tapping the vast pool of potential volunteer recruits.

The types of posters produced in Britain during the war can be broken down into four broad categories: recruitment (including justifying the war), government fund-raising, the Home Front and business as usual. The last includes the great mass of commercial advertising that continued to be printed throughout the war, almost in defiance of the conflict taking place across the Channel. Wartime photographs of street scenes are striking in their inclusion of posters promoting pre-war domestic products and entertainments, often sitting uneasily next to calls for young men to enlist or requests for conscientious citizens to eat less bread in support of the war effort. Some manufacturers, such as Oxo and Dunlop Tyres, featured soldiers in their advertising as a patriotic gesture, while others switched their focus to manufacturing wartime necessities (see , 1915). Such posters may have helped to unite the Home Front with the war theatres, but they also blurred the division between official (i.e. government-endorsed) and unofficial notices. As the war progressed, this blurring of origin became more pronounced, but it was largely inevitable as both types of poster were often produced by the same designers working for the same advertising agencies.