Print ISBN: 978-1-56037-263-9

Epub ISBN: 978-1-56037-587-6

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-56037-588-3

2003 Farcountry Press

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part by any means (with the exception of short quotes for the purpose of review) without the permission of the publisher.

For more information on our books write:

Farcountry Press, P.O. Box 5630, Helena, MT 59604,

Call (800) 821-3874, or visit http://www.farcountrypress.com

Produced in the United States of America.

PREFACE

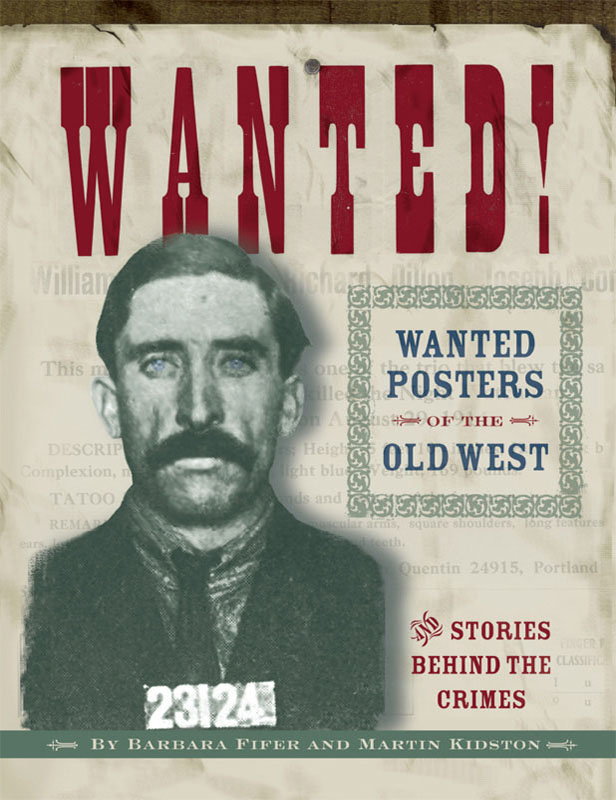

A sheriffs deputy was cleaning out the basement of the Missoula County Courthouse one afternoon in the 1970s when he stumbled across a stack of wanted posters dating back to the early 1900s.

The nearly 200 documents, some faded and torn, told stories of murder, theft, cheats, broken promises, and daring escapes.

Intrigued, the deputy showed the posters to Missoula County Sheriff John C. Moe. Being a career lawman, the sheriff took an immediate interest in the newly found material.

I looked them over and decided they would be of interest to historians, Moe said. I looked them over and thought, Well, Ill put them together in a book.

Moe donated the collection to the Historical Museum at Fort Missoula, in Montana, in 2003, and a selection of the documents is presented here. Sources of information for the introduction, chapter openings, and stories are listed in the bibliography.

INTRODUCTION

ON THEIR OWN

E arly in the twentieth century, every county in the western United States had a sheriffs department and the growing cities had police forces. Each of these law enforcement agencies worked largely alone, covering its turf and doing the best it could without the national data and communications networks so familiar today. Western sheriffs and police departments had to communicate by mail, telegraph, and telephone, spreading the news of wanted fugitives to their known haunts and along likely paths of escape: roads and railway lines.

When they rejected European government in 1776, Americans also rejected a national police force. The only federal officials with arrest power were members of the U.S. Marshals Service, whom the Treasury Department regularly hired after the Civil War to track counterfeiting of the currency that nationally chartered banks produced. The marshals were not immune from state laws, though, and until 1889 states could charge them for imagined or actual crimes committed in the line of duty. These officers did not even draw salaries until 1896, but were paid on a fee basis.

When needed, the Justice Department temporarily borrowed agents from the Secret Serviceuntil Congress allowed President Theodore Roosevelts attorney general, Charles Bonaparte, to create the Justice Departments own Bureau of Investigation in 1908. Two years later the department had thirty-four special agents who could investigate only fraud in land sales or involving national banks or bankruptcy, and antitrust cases, involuntary servitude, and immigrant naturalization.

The Mann Act in 1910 banned transporting women across state lines for immoral purposes, and the bureau seized it to go after criminals who had broken only state laws but traveled out of state with women. The 1919 National Motor Vehicle Theft Act gave Bureau of Investigation agents an additional tool, but it would be sixteen more years until their employer became the Federal Bureau of Investigation. And not until 1934 could the FBIs G-mengovernment menarrest suspects.

Private industry stepped in to fill the national police void in 1850, when Scottish immigrant Allan Pinkerton founded the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, its logo the eye that never sleeps. His agents were willing and able to cross jurisdictional boundaries that stopped government agencies. Within five years, the Pinks had contracts with several national railroads to protect their lines. Wells Fargo added detectives to its staff in 1852, and the Brinks Armored Car Company came along in 1859. Other private detective agencies popped up, but Pinkerton outweighed them as it opened offices in major cities around the United States and in Canada.

All were ready to go to work when two new types of crime were invented.

At Malden, Massachusetts, in December 1863, Edward Green committed the nations first armed bank robbery, killing the bankers son in the process. Just before he was hanged for murder in February 1866, Jesse and Frank James and nine sidekicks began the civilian career that continued their Civil War guerrilla tactics: They robbed a bank in Liberty, Missouri. That October, the Reno Brothers lifted $10,000 from a railroad train at Seymour, Indiana. The James Gang discovered train robbery in July 1872, taking a $4,000 shipment of cash along with $600 from passengers pockets. These new types of robbers all rode horseback until Henry Starr robbed a Harrison, Arkansas, bank in February 1921 and escaped in a stolen Stutz Bearcat automobile.

Both private firms and local law enforcement agencies communicated with wanted circulars sent to likely locations, asking for help in capturing and holding fugitives until one of their officers could arrive. Rewards were a hoped-for source of income for deputy sheriffs; the Pinkerton agency and its employees never accepted reward money.

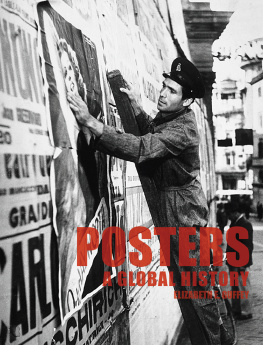

Posters advertising for information about fugitives had been around since the printing press met a literate-enough population. When Louisiana privateer Jean Lafitte was targeted by Governor William Claiborne in 1813, state-printed posters offered $500 for the pirates capture. (Lafitte patriotically attacked only vessels of U.S. enemies.) Within a week, Lafitte replied with his own posters promising $1,500 for Claibornes delivery to pirate headquarters on the Gulf of Mexico.

Early posters were printed in small quantities and distributed locally. They listed names but had no picturesthe locals knew what one another looked like. Wanted posters in the Old West were not plastered around as generously as movies show them; as this volume demonstrates, they addressed fellow officers more than the public.

STATE OF THE ART

The sheriffs and police did their best to create word pictures of the fugitives, but many physical characteristics such as clothing, hair color, or amount of facial hair were easily changed. Officials listed the best details they had on what was not so easy to alter: limps, manner of speaking, and scars. The relative commonness of scars from gunshot wounds mentioned on these posters certainly shows that career criminal is a later term for an old type of bad guy.

It was a bonus if the officer could describe the type of honest labor a fugitive might take, as well as the social milieu he would seek, often the company of sporting or lewd women in saloons or pool halls.

As Europe and then the United States became more mobile via railroads, and cities became more densely populated, law enforcement struggled to invent better ways to identify traveling criminals, as well as law-abiding citizens. Applied science was improving life in many ways, and police officials turned to it. Beginning after the Civil War, photographs, body measurements, and fingerprinting became the hot new technologies for criminal identification.

Many of the posters in this book include the mysterious numerals of the Bertillon measurement system and the Henry, Parke, or other fingerprint-sorting systems, and/or rare mug shots.

Next page