Contents

Copyright 2012 by The Library of Congress

Preface copyright 2012 by Brooke Gladstone

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

Let America Be America Again from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, Associate Editor, copyright 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes. Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc. Reprinted by permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.

Complete art credits appear from .

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Number: 2011933425

Ebook ISBN9781594749957

ISBN9781594745546

Print book designed by Doogie Horner

Production management by John J. McGurk

Editorial contributions by Robert Schnakenberg

For the Library of Congress:

Director of Publishing: W. Ralph Eubanks

Project manager and image editor: Amy Pastan

Contributors: Ralph Eubanks, Aimee Hess, Jonathan Horowitz, Elizabeth McDonald, Linda Osborne, Amy Pastan, Susan Reyburn, Maria Snellings, Sarai Reed, David Trigaux, Margaret Wagner, and Tom Wiener

Special thanks to Jan Grenci in the Department of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress, for providing access to the collections and for her other significant contributions to this project.

Additional thanks to Helena Zinkham, Barbara Natanson, and Kit Peterson in the Library of Congress Department of Prints and Photographs, the staff of the Library of Congress Duplication Services, Denise Gallo and Stephen Yusko of the Library of Congress Sheet Music Collection, Michelle Krowl in the Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Dodge Chrome, and Athena Angelos.

Quirk Books

215 Church Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

quirkbooks.com

v4.1

Contents

1828:

1828:

1832:

1836:

1840:

1840:

1844:

1844:

1848:

1848:

1848:

1848:

1852:

1856:

1856:

1860:

1860:

1860:

1864:

1864:

1868:

1868:

1872:

1872:

1876:

1880:

1880:

1884:

1888:

1888:

1892:

1896:

1896:

1896:

1900:

1900:

1904:

1904:

1908:

1908:

1912:

1912:

1916:

1916:

1920:

1924:

1924:

1928:

1928:

1932:

1936:

1936:

1936:

1940:

1944:

1944:

1948:

1948:

1952:

1952:

1956:

1960:

1964:

1964:

1968:

1968:

1968:

1968:

1968:

1968:

1968:

1972:

1972:

1972:

1972:

1976:

1976:

1976:

1976:

1980:

1980:

1980:

1984:

1984:

1988:

1988:

1988:

1992:

1992:

1996:

1996:

2000:

2000:

2000:

2004:

2004:

2004:

2008:

2008:

2008:

PREFACE

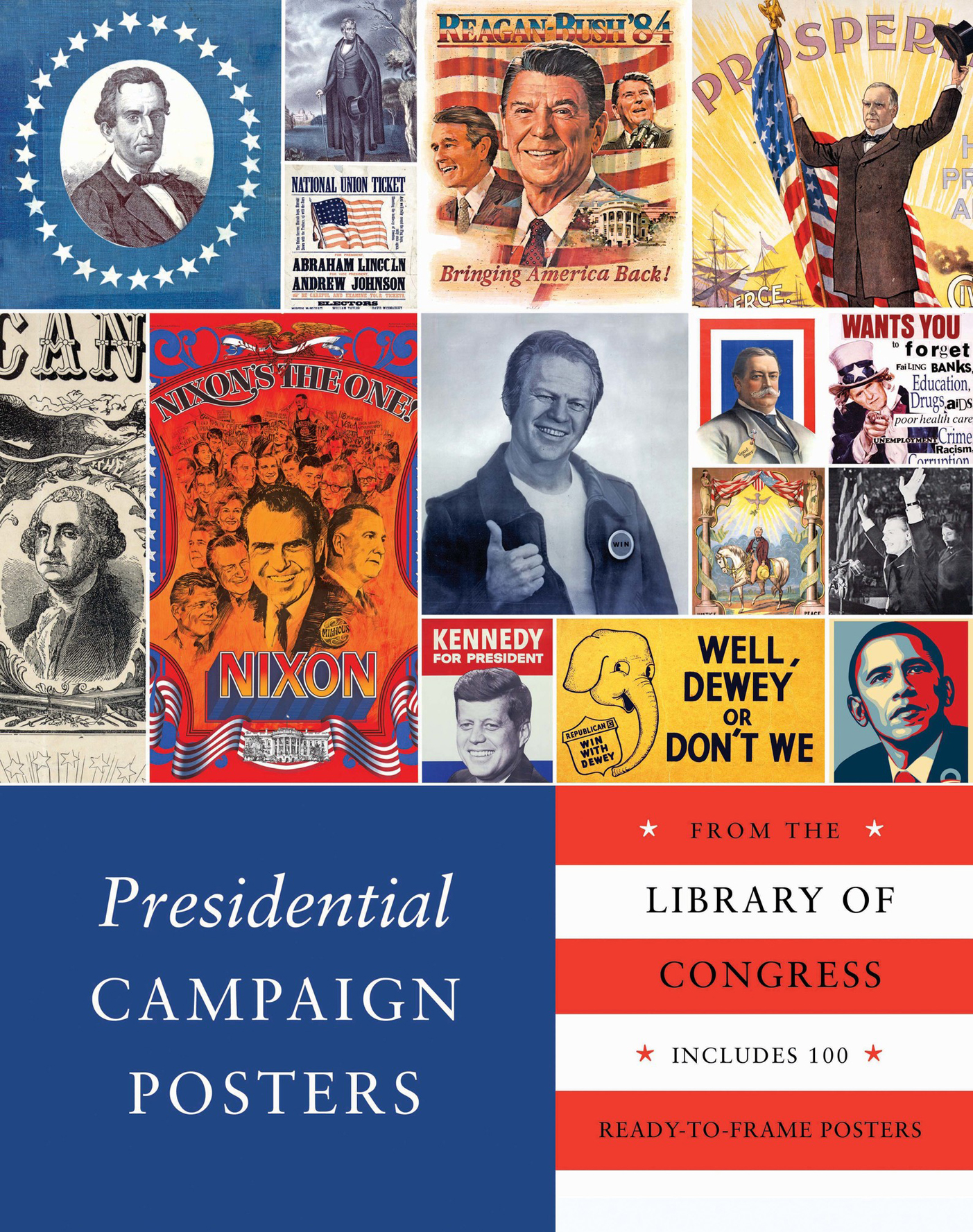

W e media consumers are far too jaded by national politics to be influenced by campaign posters, right? We all know that posters are blatant manipulations, intended not to inform but to enlist. They emphasize faces and catchphrases. They condense complicated issues into jagged little pills. They are blunt instruments.

At the same time, the most effective campaign posters of every era leave as much as possible to the voters imagination. They are like Japanese manga: the less detailed the image, the more easily we can identify with the candidate, the more space for projecting our dreams. The more specific the image, the greater the risk of creating a feeling of otherness, which translates into death at the polls.

Consider the most celebrated example of campaign art in recent years: Shepard Faireys Warhol-esque poster for Barack Obamas 2008 run for the White House. Uncluttered, with none of the little moles and stray hairs often depicted in nineteenth-century candidate etchings, it lacks even the presidential hopefuls name. It contains a message of the purest kind, in the form of a single word: hope.

This poster presented far more than a focused portrait of youth, strength, and sobriety (though it communicated all of those things, too). It managed the stunning feat of portraying a black presidential candidate while visually overcoming the otherness of being black in America. Faireys inspired rendering of an evolved, postracial America turned otherness on its head. America saw this mythic image of itself and applauded. Like all great political art, the Hope poster did not merely brand a candidate; it branded America. It branded us.

And in fact, that is what campaign art really is selling. Fundamentally, it isnt pitching politicians; its hawking images of America. The America we yearn for. Or, when the message is negative, the America we fear.

Its a truism that Americans cast their votes for candidates not on policy but on character. We vote for the person whom we want to be our public face for the next four years, the face the nation sees when it looks in the mirror. Consider just a handful of examples among, well, every winning candidate. Harry Truman, John F. Kennedy, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush were not elected on their experience or qualifications, but on who they seemed to be.

Give em Hell Truman and the language-mangling Bush were portrayed as rough and ready regular guys, as opposed to their effete and supercilious opponents, John Dewey and Al Gore (and, later, John Kerry). Kennedywhose slogan was Leadership for the 60swas the heroic, handsome harbinger of an America bursting with vim and vigah running against Richard Nixons stooped and sweaty status quo. Reagans posters depicted optimism tempered by the wisdom of age. His campaign emphasized rebirth (Bringing America Back!) while his opponent, Jimmy Carter, seemed steeped in a self-diagnosed malaise. Who wants to live in an America like that?

What is perhaps most striking about this collection of posters from the Library of Congressour oldest federal cultural institution, and one that serves as Americas memoryis what it reveals about the unchanging nature of American politicking. In the 1876 race between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel Tilden, Tilden was dubbed Slippery Sammy, barely a hairsbreadth from the Nixon epithet Tricky Dick. These echoes are uncanny, considering that early campaign posters predated modern advertising, marketing, and branding, not to mention the now never-ending research into the psychology of primary colors, the semiotics of sans serif, and the syntactics of the sound bite.

In these posters, we see the same posturing, the same accusations (of corruption, of moral turpitude) and insinuations (of suspicious religious beliefs, of hidden affiliations) hurled across party lines through the centuries. We see in black-and-white and color that the incivility that modern Americans decry as symptomatic of a sick political system has, in fact, been with us always.