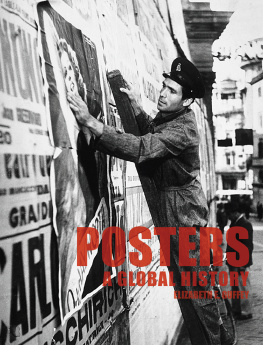

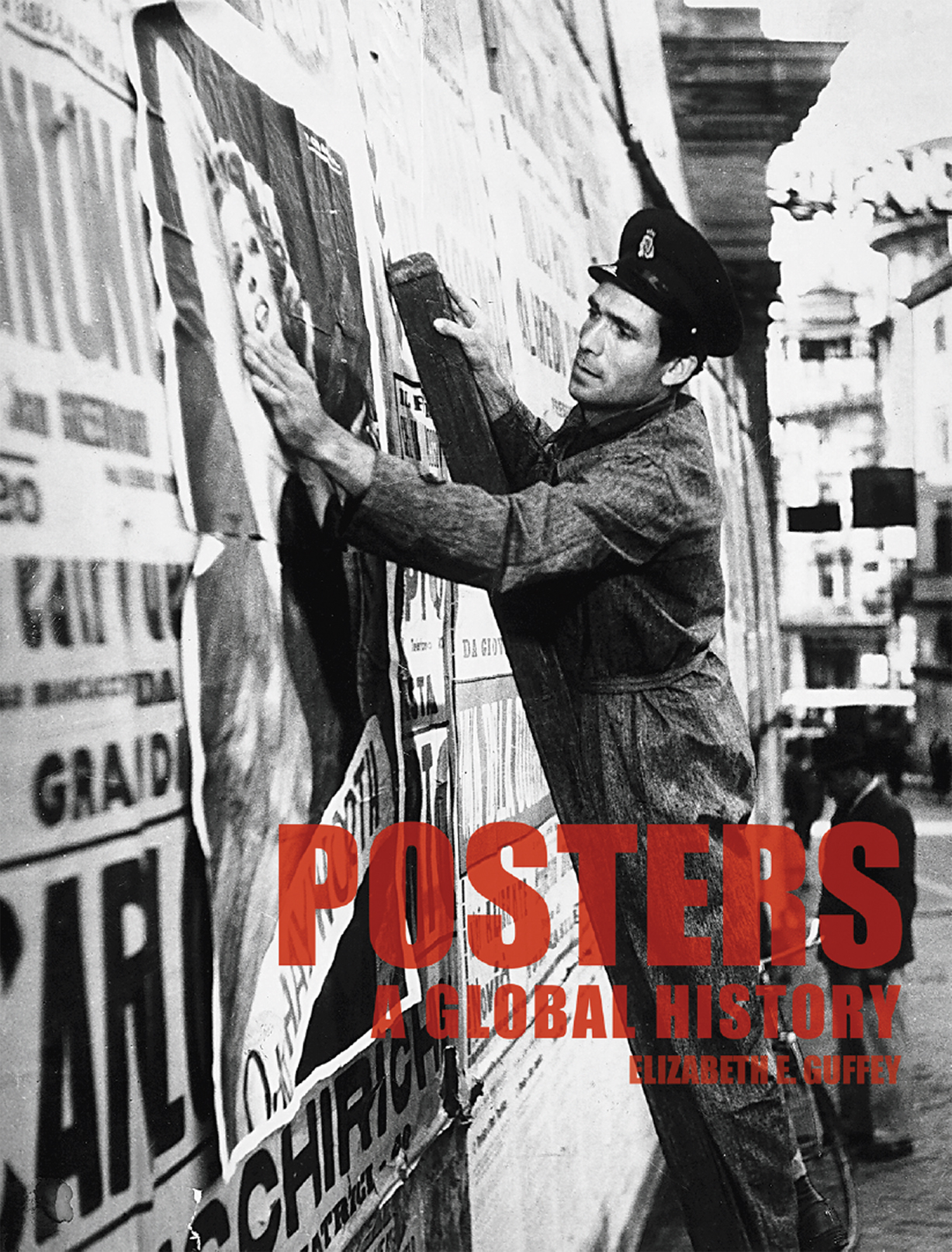

POSTERS

POSTERS

A GLOBAL HISTORY

ELIZABETH E. GUFFEY

REAKTION BOOKS

To Matt and Ellen

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2015

Copyright Elizabeth E. Guffey 2015

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in China by 1010 Printing International Ltd

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

eISBN: 9781780234113

CONTENTS

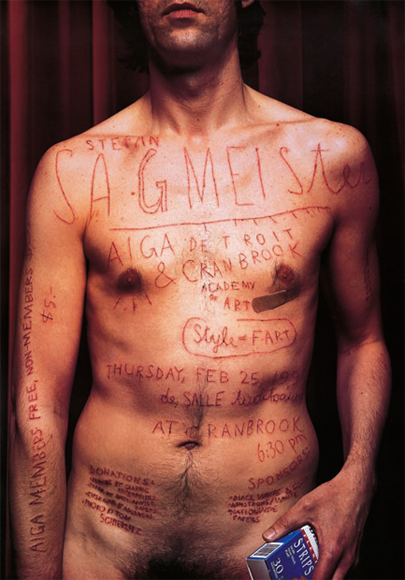

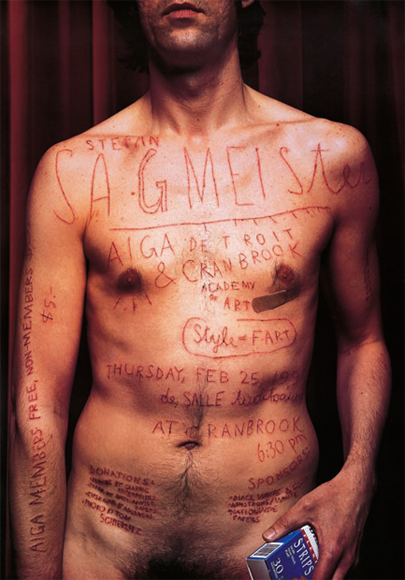

Stefan Sagmeister, poster for AIGA lecture, Cranbrook, Michigan, 1999.

INTRODUCTION

In 1999, an intern cut letters into the skin of Stefan Sagmeisters torso and arms for more than eight hours. Then Sagmeister was photographed, and he used the resulting image in a poster announcing his lecture at Cranbrook Academy of Art, near Detroit. Now an icon of contemporary design, the poster opens up multiple discourses about the body in the second millennium, with allusions ranging from exhibitionism and tattooing to sadomasochist subcultures and even the self-injurious practice of cutting. The poster announces the date, time and place clearly enough, but the image of incised flesh and rising welts challenges us to read the information; while functioning as an announcement of a specific event, it serves as well as a desperate cry to draw attention to the poster itself. Sagmeisters plea speaks volumes. But how did we get to the point of Sagmeisters mute blandishment?

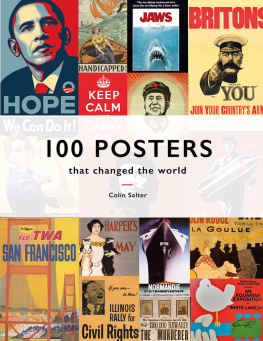

Moving from Paris cabaret advertisements to Soviet propaganda to San Francisco psychedelia, the history of the poster is already well ensconced in books, exhibition catalogues and other written records. But this is more than a story of stylistic innovation or a series of topical messages printed on paper: it is also a tale of posters as things, of material forms with which we spend our lives. Posters endure as one of the most permanent and solid forms of visual communication, and they exert a palpable physical presence, shaping spaces while reflecting and altering human behaviour. Posters, for instance, can establish zones of behavioural expectation: Work Hard to Increase Fertilizer Production! They can provide a unified voice to large numbers of people: Vote for Green! They can even assert ownership of space itself: Lebanon is Christian. After a century and a half of innumerable uses by various people, posters remain uniquely positioned to materialize the increasingly immaterial nature of visual communication.

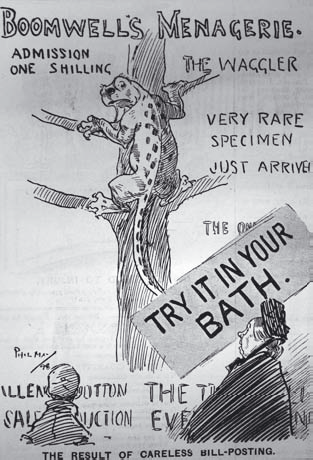

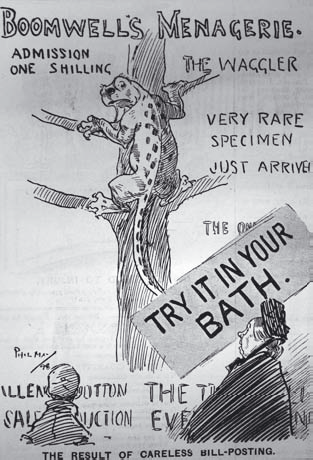

A history of posters as things may well start similarly to familiar narratives, with posters emerging in the capitals of Europe and North America as an outgrowth of mass production. Indeed, in this early stage of their history, posters were little more than communications of text and/or image, printed as multiples on paper and hung in the public realm. Posters birth was attended by the Industrial Revolution, in the tight, cluttered walls and side streets of Paris, London and New York. Yet the spaces into which posters were placed were not in any sense a tabula rasa: the poster materialized in a culture where printing was already well established and valued, and posters made these spaces over into one of the most visually and verbally saturated environments in human history. The culture of posting only increased throughout the nineteenth century, with nearly any and every available surface of urban space crowded with a dense cacophony of handbills and advertisements. Posters began to reshape this typographic landscape through their sheer size and physical presence. They also transformed the nature of reading and communications: the brash, crass instance of Victorian posters and handbills cut across class lines and bent reading from a leisurely and physically private exercise into a distracted public act.

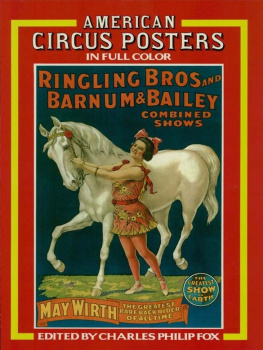

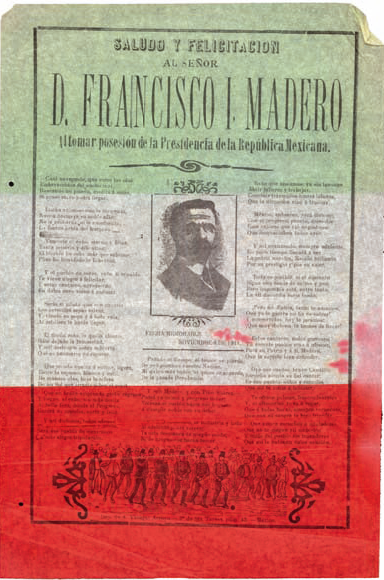

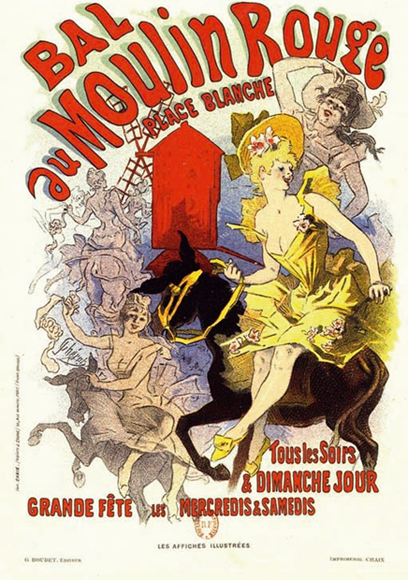

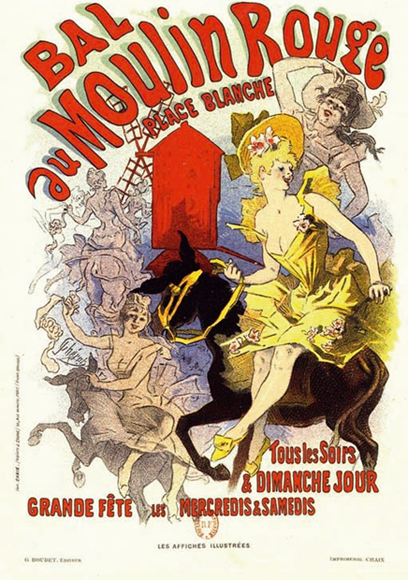

The result of careless bill-posting: a cartoon from Punch (1898).

Traditional histories usually note that posters came into their own with the widespread use of chromolithography in the late nineteenth century, as artists pushed illustrated posters from curious ephemera to become things of beauty. Yet this change also came from significant social shifts and economic upheaval. For instance, the bounding and effusive female cherettes that typify Jules Chrets work were given life not only through his skilful adoption of lithographic printing techniques but also by the lifting of Frances traditionally strict censorship and bill-posting laws in 1881. The elegant, daring compositions of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Thophile Steinlen and Alphonse Mucha echo the days artistic avant-garde but also document the near-electric charge of consumers new buying power: the rapid profusion of mass-produced cigarettes, soaps and other consumer goods enabled the poster to blossom in Paris and spread throughout Europe. For these reasons, the late nineteenth century is usually hailed as the golden age of the poster.

Jos Guadalupe Posada, Saludo y felicitacin al Seor D. Francisco I. Madero, 1911. |

|

Jules Chret, Bal au Moulin Rouge, 1896.

Thophile Steinlen, poster for sterilized milk, 1896.

Adolfo Hohenstein, Chiozza e Turchi soap poster, 1899. |

|

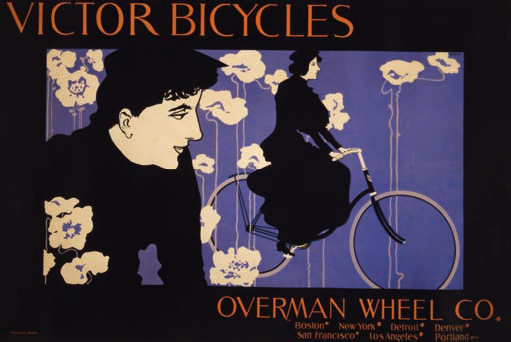

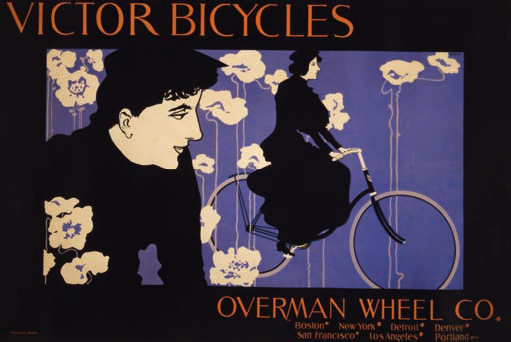

Will Bradley, Victor Bicycles, c. 1895.

Most histories note that the illustrated French poster was quickly rivalled in London and New York. The new presence of illustrated posters throughout the urban spaces of Europe and America changed some public perceptions. As large, colourful posters began to command the spaces of public streets, markets and squares, the format itself took on a civic respectability never afforded to Victorian handbills. The Beggarstaff brothers in Britain, Toulouse-Lautrec and Steinlen in France and Edward Penfield or Will Bradley in North America designed commercial advertising posters that were nonetheless seen as public decorations and even regarded as art; the very streets of Paris, New York and London were lauded as the poor mans picture gallery.

Whether perceived as civic art or public nuisance, nineteenth-century illustrated posters were unequivocally capitalist, urging consumption even as they were themselves consumed. As posters grew in popular appeal, dedicated collectors began saving, trading and buying them for ever-increasing sums. The poster was perceived as both public image and physical object: posters still wet with paste were pulled off the sides of buildings, unpeeled from railway carriages and even bought directly from printing houses. For the dedicated devotee, the editor of