Sommaire

Pagination de l'dition papier

Guide

Copyright 2016 by Ronald G. Shafer

All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61373-543-5

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Shafer, Ronald G., author.

Title: The carnival campaign : how the rollicking 1840 campaign of

Tippecanoe and Tyler too changed presidential elections forever / Ronald G. Shafer.

Description: Chicago, Illinois : Chicago Review Press Incorporated, 2016. |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016019215| ISBN 9781613735404 (hardback) | ISBN

9781613735435 (epub edition) | ISBN 9781613735428 (kindle edition)

Subjects: LCSH: PresidentsUnited StatesElection1840. | Harrison,

William Henry, 17731841. | United StatesPolitics and

government18371841.

Classification: LCC E390 .S53 2016 | DDC 324.973/58dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016019215

Typesetting: Nord Compo

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This digital document has been produced by Nord Compo.

To my wife, Mary Rogers, and our children, Kathryn Shafer Rivers, Daniel Rogers, and Kaitlin Rogers. And to our granddaughters, Kaylie Ryan Rivers and Veronica Rogers Nunley.

INTRODUCTION

The most remarkable political contest ever known was that of 1840.

Author A. B. Norton, 1888

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too. Just about everybody has heard of that famous political slogan. But what does it mean?

The catchy phrase refers to the Whig Partys 1840 presidential ticket of William Henry Old Tippecanoe Harrison and John Tyler. It became their battle cry in their campaign against Democratic president Martin Van Buren. But the significance of that campaign goes far beyond the memorable phrase.

The 1840 campaign, many historians agree, was the mother of modern presidential contests. For the first time, a political party launched a full-on grassroots campaign, generating massive rallies across the country. The gatherings were part three-ring circus and part old-time revival meeting, complete with marching bands, floats, and political preaching. There was even a traveling Bearnot an animal, but a speech-making blacksmith by that name. Many of the parades featured the worlds tallest man, standing at more than seven and a half feet. All of this was put to music with hundreds of campaign songs. Nothing like it had ever been seen before. It was the beginning of presidential campaigning as entertainment.

Harrison became the first presidential candidate to campaign for himself and give his own speeches to support his election. And surrogate speakers in unprecedented numbers took to the hustings in state after state. To the shock of many people, women began playing an active role in presidential politics. Big campaign donations emerged as an influential factor. The debate over small government versus government intervention began. The Whigs, meantime, mounted the first image advertising campaign for a presidential candidate, establishing forever a basic tactic of political campaigns. It is called lying.

The chief target of Whig ridicule was the sitting president, known as the Little Magician. But both sides engaged in plenty of mudslinging. Personal attacks were so vicious that one might have thought the candidates should be in the jailhouse instead of the White House. The rollicking run of Tippecanoe and Tyler Too changed presidential campaigns forever.

It all began in the winter of 1839 in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

A COMPROMISE CANDIDATE

[The Whig nominees] imbecility and incapacity is universally acknowledged by every candid man who is personally acquainted with him.

Ohio Statesman, an anti-Whig newspaper

Suppose they held a presidential convention and none of the candidates showed up. That was the situation on the morning of Wednesday, December 4, 1839, as delegates to the Whig Partys first-ever presidential convention crowded into the newly rebuilt, redbrick Zion Lutheran Church in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

None of the three men seeking the Whig nomination for the 1840 election was even in town. Not one of them planned to attend the convention to give an acceptance speech if nominated. Nor could they direct their candidacy from home, because the telegraph and the telephone hadnt been invented yet. At the time it was unthinkable for a presidential candidate to campaign openly or give speeches for himself. It had never been done. The office sought the man, not the other way around.

The great Kentucky statesman Henry Clay was the top betting choice going into the convention. The sixty-two-year-old senator was the man who had said earlier in 1839, I had rather be right than be president. He was lying through the snuff in his nose. Senator Clay would do almost anything to become president.

Trailing behind were two military heroes. One was fifty-three-year-old General Winfield Old Fuss and Feathers Scott. The pompous, six-foot-four-inch Scott recently had won renewed renown by helping to settle a dispute with Canada on the Maine border.

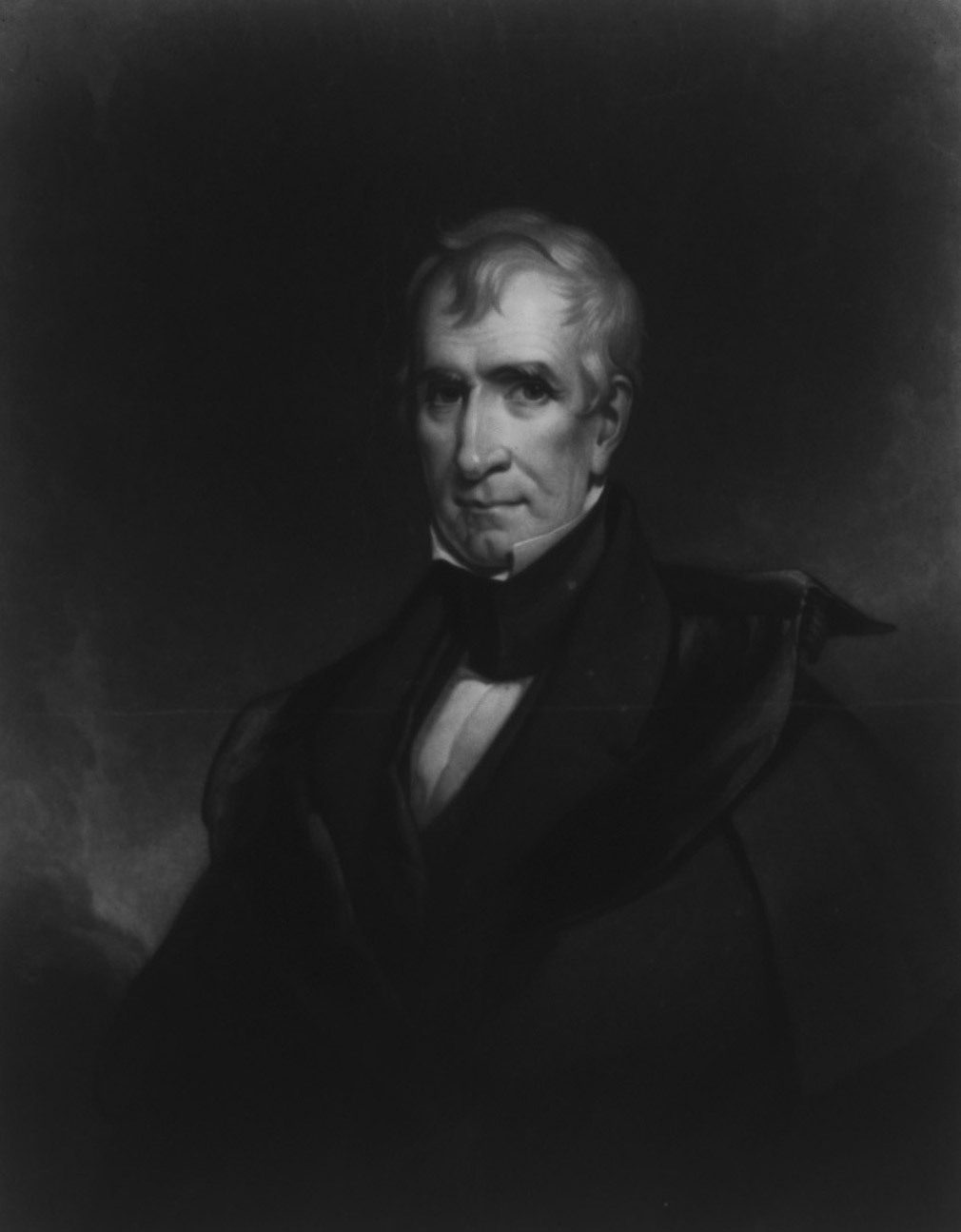

William Henry Harrison. Library of Congress

The other candidate was General William Henry Harrison. He was famed as Old Tippecanoe after winning an 1811 battle against Native Americans near the Tippecanoe River in the Indiana Territory. The problem was that at the age of nearly sixty-seven, Harrison would be the oldest man ever to run for president. Also, he had been out of politics for most of the past twenty-five years and now lived on a remote farm in Ohio.

The choice in Harrisburg was in the hands of 254 Whig delegates, all of them white males. Most arrived by train at the state capitals brand-new rail station. One delegate, John Johnston, a military officer who had served under Harrison, rode his horse from Piqua, Ohio, a distance of more than 450 miles. In cities and rural areas alike, people traveled by horseback, stagecoach, and horse-drawn carriage, as well as by train and steamboat.

The delegates came from twenty-two of the twenty-six states, stretching as far south as Georgia and as far west as Louisiana in a growing America of seventeen million people, including about two-and-a-half million slaves. (The total was slightly less than the modern population of New York State.) Politicians and lawyers dominated the state delegations, but they represented a wildly diverse mix.

The Whig Party was formed in 1834 to counter President Andrew Jackson of the Democratic Party. Whig had been the name adopted by colonists who opposed King George III during the Revolutionary War. The current Whig Party united foes of King Andrew. Its members ranged from rural farmers to urban bankers, from abolitionists to slaveholders, and from industrial titans to shopkeepers and laborers. The Whigssometimes called Republicansfavored some federal action, such as building roads across connecting states. The Democrats flatly opposed federal intervention. In this respect, the Democratic Party was more like modern-day Republicans, and the Whigs/Republicans were closer to modern Democrats.

As the convention convened, the weather was unseasonably warm following recent snows. The delegates and party officials noisily began taking seats in the cavernous church sanctuary as the morning sunlight streamed through stained-glass windows. A gentlemans business dress of the day was a cutaway suit coat, a vest, and tight trousers. A large scarf-like cravat was tied around the removable high collar of a white linen shirt. Men usually were clean-shaven, but with longish hair that flowed into lengthy sideburns.