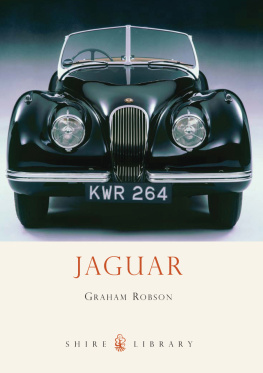

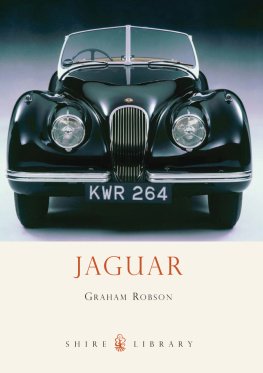

JAGUAR

Graham Robson

SHIRE PUBLICATIONS

The XK120 sports car was previewed in 1948 and soon proved that it could exceed 125 mph, making it the worlds fastest production car at this time.

This was the badge that graced Jaguar cars from their introduction in 1945. It would be modified in later years.

CONTENTS

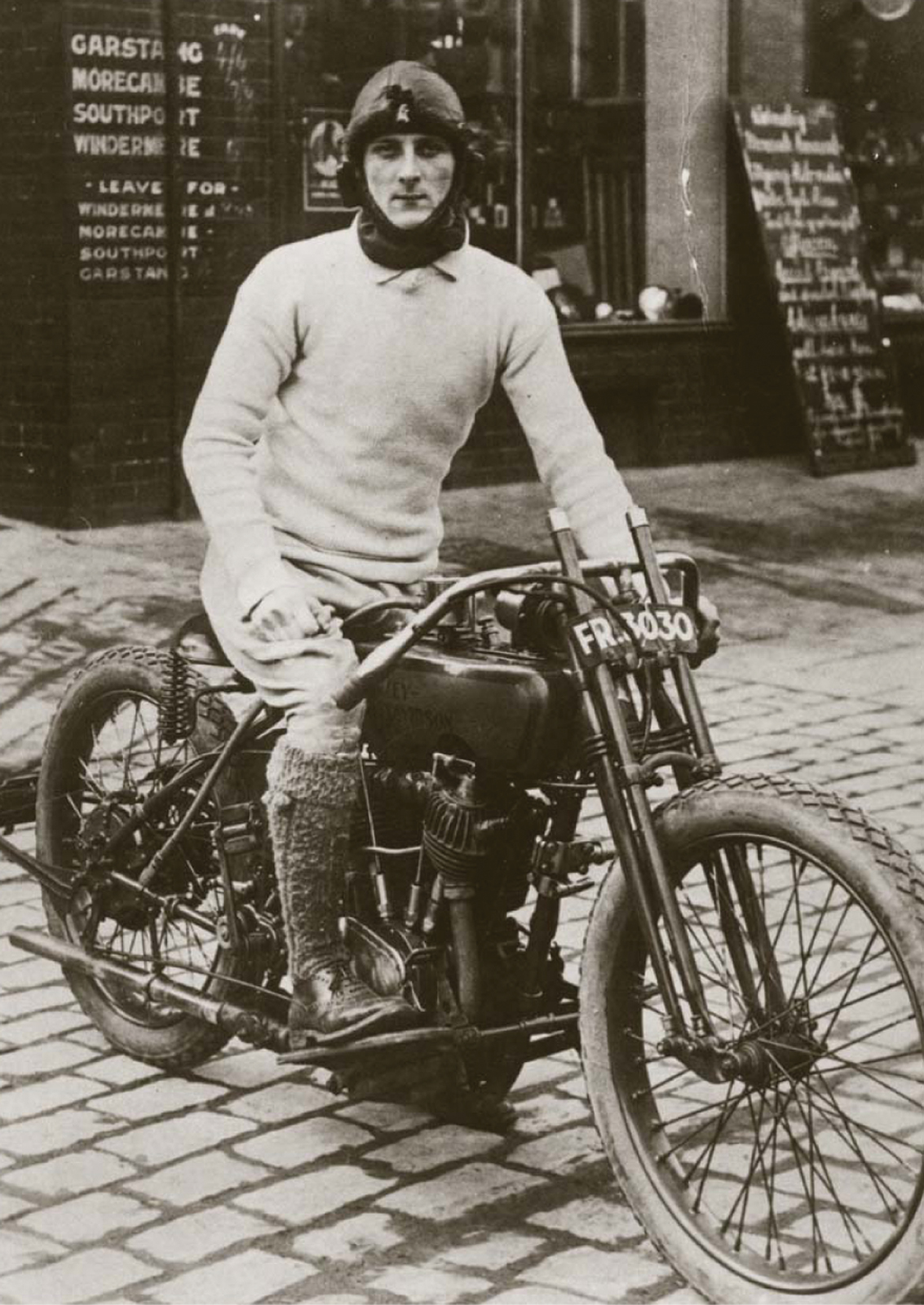

William Lyons began his business career in Blackpool, styling and constructing sidecars for motorcycles.

IN THE BEGINNING: SIDECARS AND REBODIED SPECIALS

T HE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN the Jaguar cars original ancestors motorcycle sidecars built in Blackpool and todays luxury automobiles, is total. The story of Jaguar is a fascinating one that combines elegant styling, ambition, high performance and commercial good sense.

Although the name Jaguar was not applied to a car until 1935, the machinery that inspired it first took shape in 1922. William Lyons, born and raised in Blackpool, started work for Crossley Motors in Manchester in 1918 and then dabbled with various short-term jobs in Blackpool, before meeting William Walmsley. The two young men soon got together, in 1922, to start producing motorcycle sidecars in tiny numbers, and before long it fell to Lyons to bring artistic flair to the shaping of new products. Building up to ten sidecars every week, the new concern was called the Swallow Sidecar Company which is why the first cars that they were soon to start producing were known as SS machines.

Over the next few years the business blossomed. First SS produced simple bodies, for fixing to other companies chassis; then they began to make their own chassis, and still the demand grew. By 1926 Lyons (who always seemed to have more entrepreneurial ambition than Walmsley) was looking to go beyond sidecars: they began to deal in coachbuilding, repainting, retrimming or otherwise modifying other companies cars, and they soon set about designing complete car bodies of their own.

The first SS-bodied car an Austin Seven followed in 1927, having altogether sleeker lines than the machines being produced by Austin itself at Longbridge. First seen by the public in the specialist motoring press, in May 1927, the cute little aluminium-bodied Austin Seven was available as an open-top two-seater for 175, or as a closed coup for 185. The Autocar suggested that The latest, and certainly one of the most attractive-looking bodies arranged for this car, is the Swallow saloon-coup, built by the Swallow Sidecar and Coachbuilding Co

Business was brisk from the start, but Swallow had an immediate problem in that their cramped little works at Blackpool could not produce more than two cars a day, the varnishing shop being the limiting factor. By comparison, the company was already building up to one hundred sidecar bodies every week.

Sir William Lyons, 190186, the founder of Jaguar.

Lyons did not allow this to hold the company back, for he was thinking far into the future. Only months after the Austin Seven Swallow had been shown, the company produced its second offering, which was significantly larger (and therefore more costly): the Morris-Cowley Swallow, which sold for 210. The problem of space, however, soon came to a head when Lyons was introduced to Henlys Ltd, the big London-based motor traders, for they placed an immediate order for five hundred cars, and demanded delivery at the rate of twenty cars every week. Furthermore, they wanted to see a saloon version of the original style produced as well, which meant more work for Lyons, who was now becoming the styling genius he would remain for more than forty years.

Soon the Blackpool premises were bursting at the seams, and the tight-knit little workforce was working huge amounts of overtime to keep up with demand. Lyons and Walmsley then concluded that they would have to move away from Blackpool. The centre of Britains motor industry at that time was unquestionably Coventry, and Lyons spent much time there searching for new premises. A suitable site was eventually found in the shape of a disused shell-filling factory in Whitmore Park, Foleshill, Coventry.

This was the style of the original Swallow sidecars for which William Lyons was responsible.

When the factory was ready in 1928, the company invited all its Blackpool staff to move south (which most of them did), took on more workers in Coventry itself, and was up and running only days after the complex move of cars, part-built cars, components and equipment had been accomplished. No sooner had this been done than the company started improving the property it had leased; they resurfaced the access road and secured the right to expand into other empty buildings alongside. Their target of producing fifty cars every week was rapidly reached.

Before long, Lyons began to look around for new products to add to the Austin Seven cars, which were still the companys staple product. Several new models were introduced, some selling better than others, the theory being that Swallow would produce completely new body styles, but that the original rolling chassis would be retained. Among these models were an Alvis-Swallow, a Fiat 509-Swallow and a Swift-Swallow, but all these were soon to become financially insignificant in comparison with Swallows next big tie-up which was with Standard.

Series production of Swallow sidecars at Blackpool in the mid-1920s.

The Austin Swallow saloon of 1927 was the first complete car to be styled by William Lyons. His styling career would cover forty-five years.

The timing was important. Standard, then and later an important car manufacturer in Coventry, had been in decline, but was rapidly being revived by a new general manager, Captain John Black, who wanted to expand the companys sales. The opportunity came almost at once, when Lyons worked his styling magic on the latest Standard Nine. By early 1930 a new Standard Nine-Swallow was on sale, for a mere 250, and was soon joined by another Standard-based car, this running on the much larger six-cylinder Ensign chassis.

This was only the beginning of what would develop into a close, tempestuous, but ultimately climactic relationship. William Lyons wanted to push ahead with his ideas for future cars and saw Standard (for whom John Black was similarly ambitious) as a suitable business associate. The Autocar