T he Royal Air Force has played a role in almost every campaign undertaken by the United Kingdom since 1918. Looming large is the Second World War, when the RAF contained over a million personnel and played a key role in delivering final victory. Aerial operations continue in 2018 in the Middle East, an area familiar to the RAF of the 1920s and 1930s, while the renewed threat from Russia in the twenty-first century recalls the tensions of the Cold War.

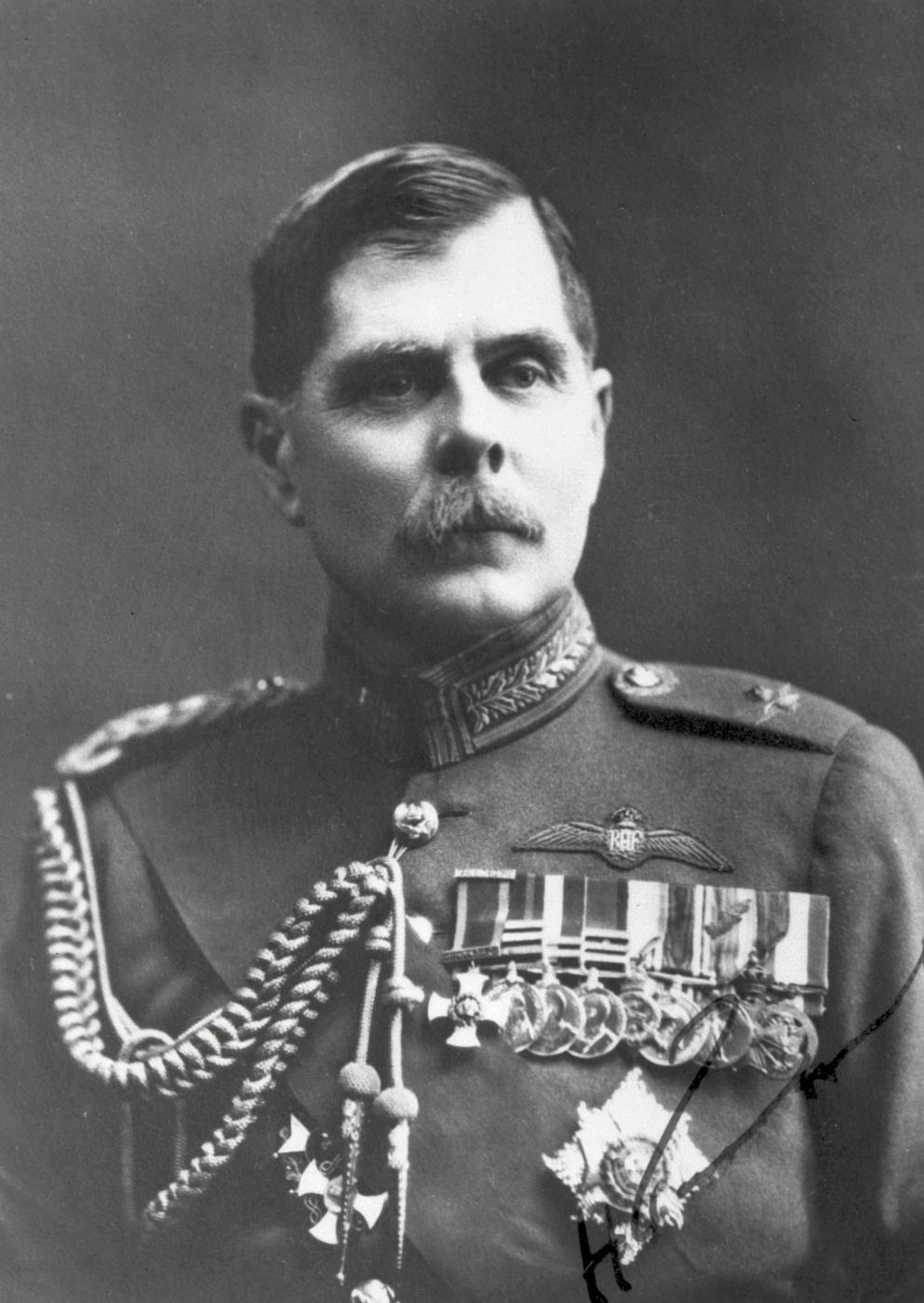

Although the structure and size of the RAF have changed, the strong foundations laid in the early years means that much of the service remains recognisable today, and the vision of Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Trenchard, the father of the RAF, of a small, highly professional cadre, remains as true now as it did at the beginning. The influence of the worlds oldest air force can be seen in the technical, organisational and cultural bonds formed over many years between the RAF and Commonwealth and allied air forces.

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Lord Trenchard, the father of the RAF.

This book is intended to be a short introduction to the RAF. Many important aspects of the air force, its organisation and its history have received only cursory mention. For those who wish to explore further, there are a vast number of books and articles covering almost every facet of the RAFs history, a few of which are listed at the end of this book. It is hoped that this slim volume may whet the readers appetite to learn more.

FORMATION (191119)

I n the early years of the twentieth century, the worlds major powers began to recognise the potential military value of balloons, airships and, in particular, aeroplanes. Great Britain was no exception and in 1911, the Air Battalion of the Royal Engineers was formed. Around the same time, the Royal Navy established a flying school at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey.

In an attempt to coordinate the aerial interests of the two services, the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), consisting of a Military Wing, a Naval Wing and a Central Flying School (CFS), was formed in April 1912. However, with only a consultative sub-committee as an inter-service authority, there was little coordination between the Military and Naval Wings. This was underlined in July 1914, when the Naval Wing separated from the RFC and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was formed.

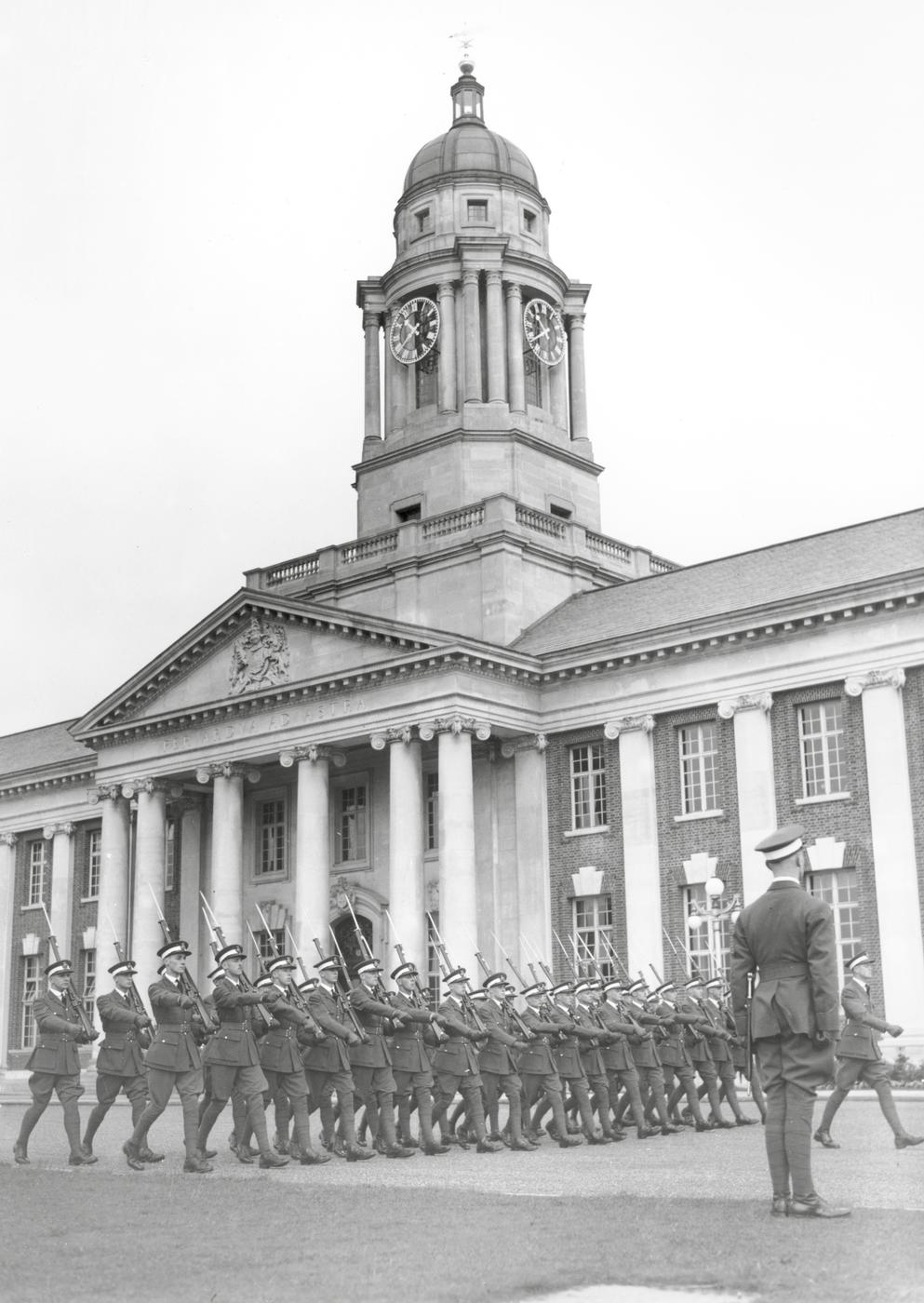

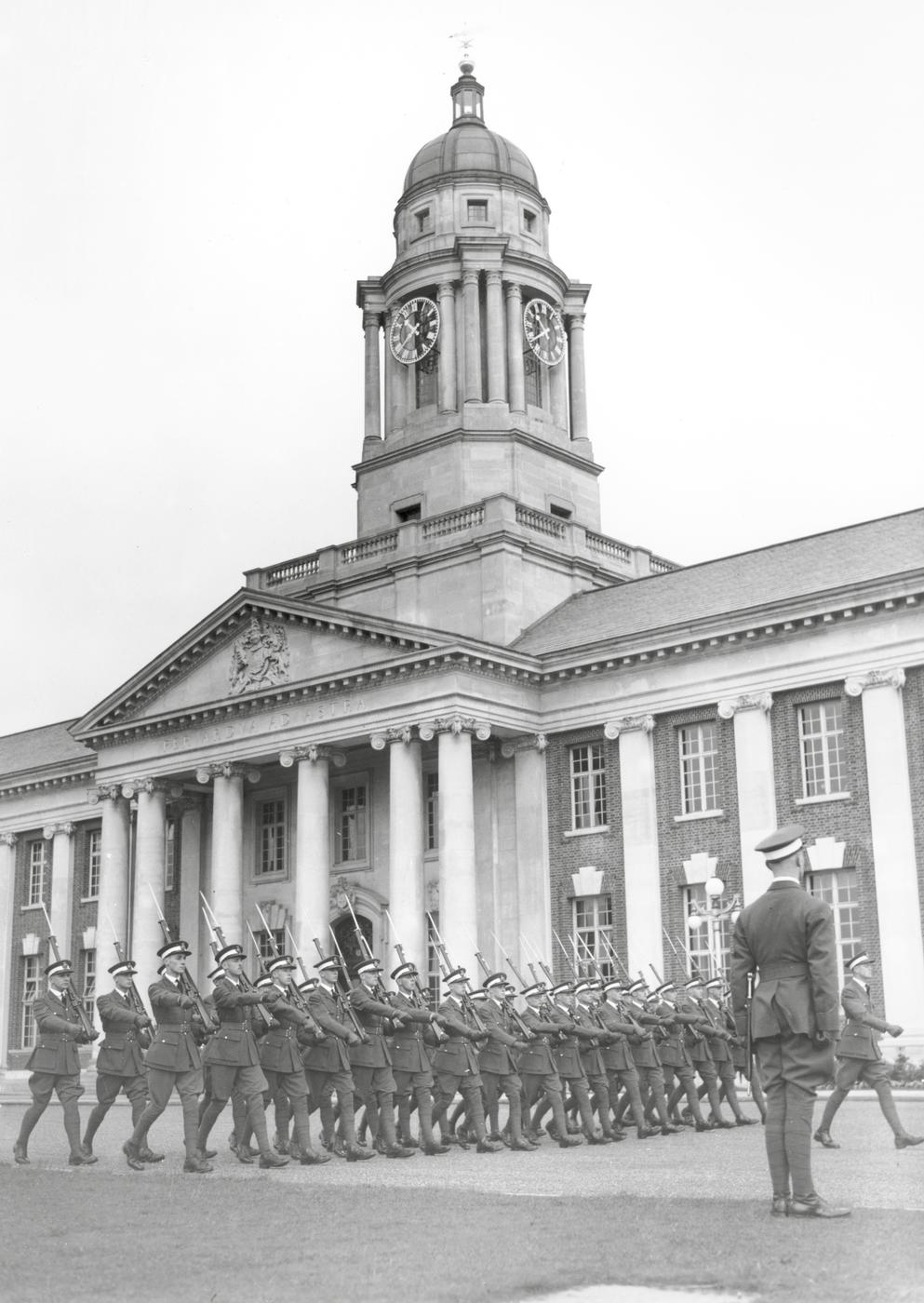

An inspection at the RAF College Cranwell, 1936. Trenchard observed, Marooned in the wilderness, cut off from pastimes they could not organise for themselves, the cadets would find life cheaper, healthier and more wholesome.

At the outbreak of the First World War, the RFC sent most of its aircraft to France with the British Expeditionary Force, and during the next three and a half years supported the army in a variety of tasks. The RNAS operated against German U-boats and airships, formed a number of squadrons to serve on the Western Front and assumed partial responsibility for Home Defence duties.

Although the RFC and RNAS eventually succeeded in defeating the German airship raids in the autumn of 1916, a much more potent threat emerged the following year when, on 7 July 1917, a formation of Gotha aeroplanes attacked London in daylight. Although casualties among the civilian population were fairly light, the feeble response by the defences caused outrage. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff, Sir William Robertson, revealed in a letter that during a cabinet meeting on the day of the Gotha raid, panic was not confined to the population at large: one would have thought the whole world was coming to an endI could not get a word in edgeways.

In response, the government commissioned a report into the state of home defences. Two reports were written by Lieutenant-General Jan Smuts, the famous Boer soldier and South Africas representative in the Imperial War Cabinet. The first sensibly recommended a single, unified command to control all the fighter squadrons, anti-aircraft batteries, searchlights and observation posts throughout the UK.

South African soldier and statesman Jan Smuts, author of a report from which emerged the Royal Air Force.

In the second report, Smuts came to three conclusions: that aircraft were of strategic importance; that the Germans realised this; and that the UKs aircraft industry was capable of supporting a strategic air offensive against Germany. Significantly, Smuts wrote of aircraft:

As far as can at present be foreseen there is absolutely no limit to the scale of its future independent war use. And the day may not be far off when aerial operations with their devastation of enemy lands and destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale may become the principal operations of war, to which the older forms of military and naval operations may become secondary and subordinate

Smuts went on to suggest that an Air Ministry should be established to coordinate planning and industrial resources and administer the new air force, which would be created from an amalgamation of the RFC and RNAS. In addition, a fleet of bombers was to be created with the specific task of attacking German industrial towns.

Although there was opposition to an independent air force, notably from the RFCs commander, Hugh Trenchard, who argued that an air force should be created after the war had ended, the government pressed ahead. On 20 November 1917, a bill to constitute an Air Ministry received Royal Assent as The Air Force Act. The merger of the RFC and RNAS officially took place on 1 April 1918, creating the Royal Air Force (RAF).

Sopwith 2F.1 Camels aboard HMS Furious for the raid on the German airship base at Tondern in July 1918. The Camels destroyed two Zeppelins in the worlds first carrier airstrike.

The creation of a new service did not have a great impact on the men in action around the world. During the final months of the First World War, the RAF fought with the army in a series of offensives, while British bombers attacked German industrial centres in a sporadic fashion and with somewhat limited success. More positively, in July 1918, the RAF carried out the worlds first carrier-borne strike, when a few Sopwith Camels took off from HMS Furious to attack the Zeppelin base at Tondern in northern Germany.

By the end of the First World War, the RAF had become the largest air force in the world, performing a wide variety of roles and making a valuable contribution to the victories of 1918.

A SILVER AIR FORCE (191939)

A fter the euphoria following the First World War had ended, it was time for sober assessments to be made. Of immediate importance was the rapid but necessary scaling down of the three services, and the RAF was no exception. There was even some doubt over the continued viability of an independent air service. Winston Churchill, the new Secretary of State for Air, asked Trenchard, now Chief of the Air Staff, to give his views on the future size and shape of the air force; a White Paper was duly published in 1919, setting out Trenchards views. In this, he emphasised strict economy, the value of training to form a small but elite cadre and the role of the RAF bomber force as a (future) deterrent. To complement this separate identity, a new uniform was designed, different medals were authorised and a revised system of organisation and ranks was adopted. Other details, such as an RAF March Past and the creation of squadron badges by the College of Arms, came into being in the following years.