CONTENTS

- Cover

- Title Page

- Table of Contents

INTRODUCTION

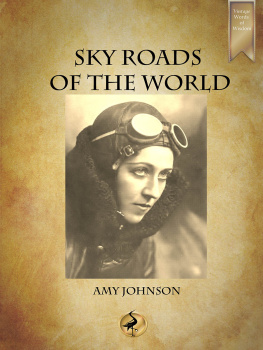

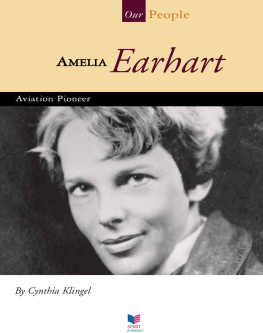

T HE STORY OF women in aviation goes back further than many imagine. Women flew aboard hot-air balloons in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and were involved in powered flight from the beginning: Katharine Wright is sometimes referred to as the third Wright brother. In later years, Amelia Earhart, Amy Johnson and others flew all kinds of aircraft, in all weathers and in all parts of the world, proving that they could fly just as well as their mal e counterparts.

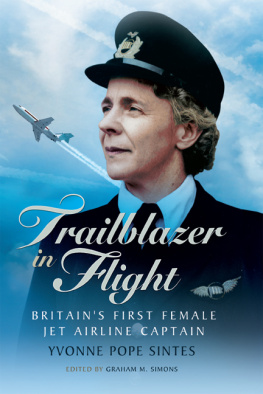

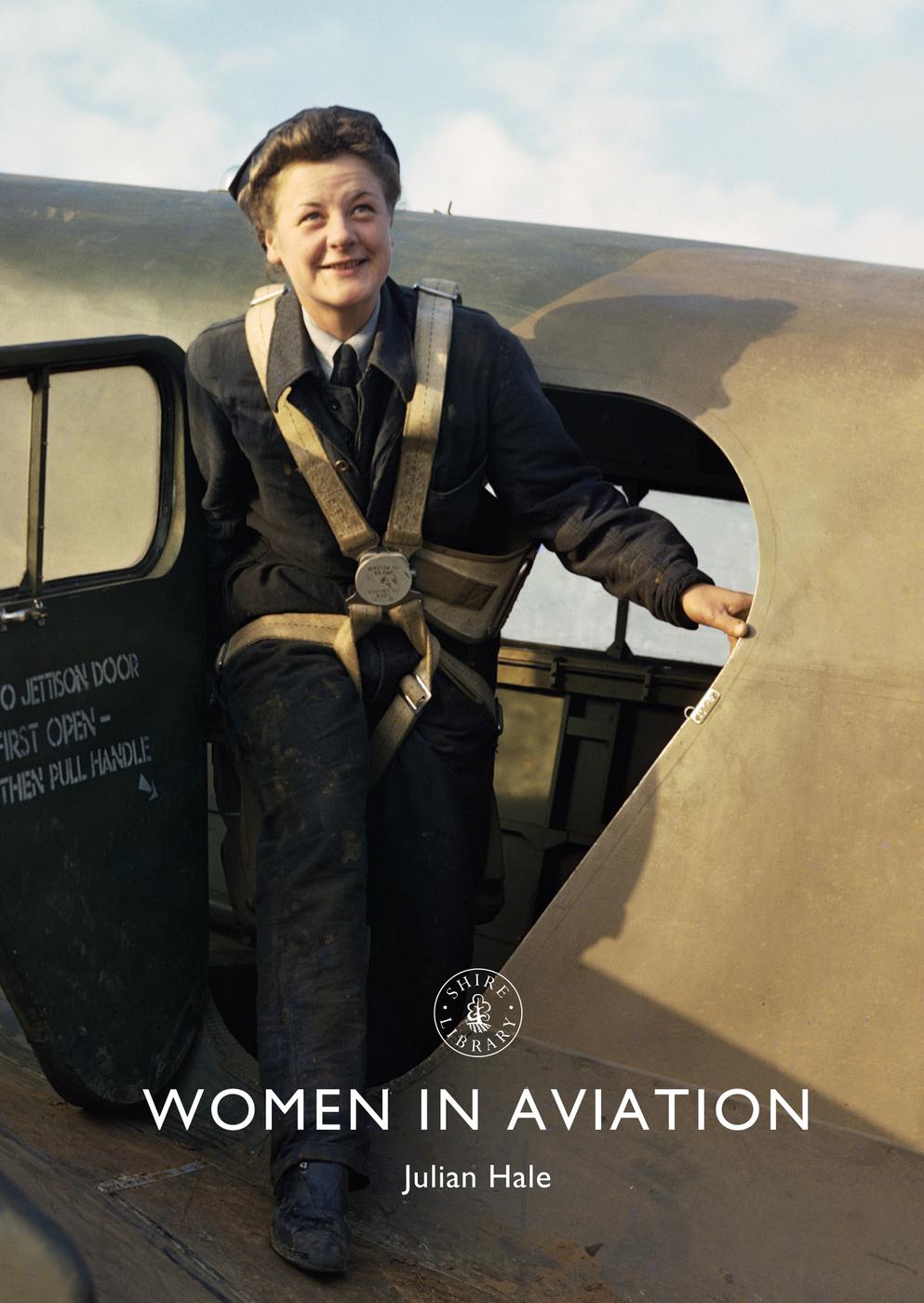

Their struggle was not easy. Although the women pilots of the British Air Transport Auxiliary received support from most quarters (and sometimes incredulity instead of resentment), others did not. Members of the American Womens Airforce Service Pilots WASPs encountered hostility in many forms from male servicemen, including the reported sabotage of aircraft. Yet attitudes evolved steadily: by the 1970s, women were flying as airline captains, air force pilots (in the USAF) and even undergoing astr onaut training.

This book is intended as a primer on the subject. The whole story of women in aviation would necessitate a much larger volume and would include the often-overlooked contributions made by women from all countries and in all fields of aviation design, manufacture, testing and support not just flying. Nevertheless, it is to be hoped that this book will introduce the reader to some of the famous (and a few of the lesser-known) personalities who have done so much for women and aviati on in the past.

THE EARLY YEARS

O N A PRIL 1912 , a woman dressed from head to foot in a purple satin flying suit, climbed into an aircraft at Dover, took off and promptly disappeared into a thick cloud. Fifty-nine minutes later, her aircraft touched down in the Pas-de-Calais. Her name was Harriet Quimby and she had become the first woman to fly an aeroplane across the E nglish Channel.

Quimby had shown great resolve several aviators, including the famous Gustav Hamel, had attempted to dissuade her from making the perilous crossing (he even offered to make the flight himself, dressed in Quimbys trademark suit). Yet her achievement was overshadowed by the sinking of the Titanic on 15 April and Quimby never received the publicity she deserved. Only three months later she was dead, when her two-seat Bleriot monoplane inexplicably pitched forward during an air display in the United States, throwing Quimby and her passenger to their deaths. She was thirty-s even years old.

Harriet Quimby became the first woman to fly the English Channel in an aeroplane in April 1912. Her flight unfortunately, in terms of publicity, coincided with the Titanic disaster.

The story of women in aviation stretches back to the eighteenth century. Frenchwoman Elisabeth Thible became the first woman to fly in an untethered hot-air balloon in Lyon in 1784. Sophie, wife of the famous pioneer balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard, became famous for her lighter-than-air exploits, but died while unwisely giving a firework display from her hydrogen-filled balloon over Paris in 1819.

The first woman to be awarded a pilots licence (in 1910) was also French: Elise Raymonde Deroche, often styled pseudonymously as Baroness de Laroche. Her career, which was notable for her survival of three near-fatal accidents, ended in tragedy when she crashed to her death in 1919.

Harriet Quimby in her trademark purple satin flying suit. Only months after her Channel crossing, she was killed in a flying accident in the United States.

In 1911, Hilda Hewlett became the first British woman to qualify as a pilot. She was born Hilda Herbert in 1864, married Maurice Hewlett in 1888 and developed an interest in motor cars. The couple met Gustav Blondeau at a motor meeting in 1909 and befriended him. The pair attended Britains first aviation meeting in Blackpool in October 1909 and, inspired, sought instruction in France before returning to the UK. They established the Hewlett & Blondeau flying school at Brooklands, among whose famous pupils was Thomas Sopwith. Hewlett won several flying competitions and in a maternal first, taught her own son to fly. It is also said that there were no accidents at her school at Brooklands a remarkab le achievement.

Sophie Blanchard was the most famous of the early female balloonists. Her signature performance was a firework display from her hydrogen-filled balloon, the last of which ended tragically in 1819.

Elise Raymonde Deroche became the first woman to gain a pilots licence. Her career was dogged by a series of flying accidents.

Hewlett and Blondeau also started their own aircraft manufacturing business before the First World War and the firm grew to become a major licenced manufacturer of other companies aircraft. It was at this point that she politely separated from her husband (who had earlier said that women will never be as successful in aviation as men. They have not the right kind of nerve.). She became known locally for driving a large car with her Great Dane in the back seat, dressing eccentrically and cropping her hair short in a masculine style. The factory made a great contribution to the British effort during the First World War, employing some 700 staff and producing over 800 aircraft. However, in common with many aircraft companies, the firm was unable to survive the post-war slump and Hewlett & Blondeau closed in 1920.

BESSIE COLEMAN

In 1921, Bessie Coleman became the first African-American woman to earn a pilots licence. After moving to Chicago, she wanted, in her own words, to amount to something and chose flying. Racial prejudice forced her to take flying lessons in France, where she successfully completed a ten-month course three months early. For the next five years she toured the USA, barnstorming and speaking at many churches and schools about race and aviation. She fought continually against racism, refusing to appear at air displays where the crowd was segregated. Tragically, while on a test flight on 30 April 1926, the mechanic flying her aircraft lost control and she fell from the cockpit to her death. Her legacy lived on with the establishment in 1929 of the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in Los Angeles, where among others, members of the famous Tuskegee Airmen learned to fly.

Hewlett emigrated with her family to New Zealand in the 1920s, where she established an airfield and flying club in Tauranga. In 1932, she flew as the first female passenger between New Zealand and the UK (the journey, via Jakarta courtesy of KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, took eleven days). The first great British female aviation pioneer died in 1943 and as requested, was buried at sea.