Author:

Eric Shanes

Layout:

Baseline Co. Ltd

61A-63A Vo Van Tan Street

4 th Floor

District 3, Ho Chi Minh City

Vietnam

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014936060

Confidential Concepts, worldwide, USA

Parkstone Press International, New York, USA

Image-Bar www.image-bar.com

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced or adapted without the permission of the copyright holder, throughout the world. Unless otherwise specified, copyright on the works reproduced lies with the respective photographers, artists, heirs or estates. Despite intensive research, it has not always been possible to establish copyright ownership. Where this is the case, we would appreciate notification.

ISBN: 978-1-78310-291-4

Eric Shanes

Salvador Dal

Contents

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

L

M

N

P

S

T

U

V

W

Y

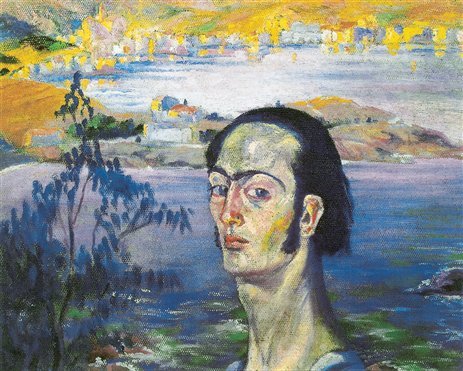

Self-Portrait with the Neck of Raphael, 1921.

Oil on canvas, 41.5 x cm .

Teatre-Museu Dal, Figueres.

Introduction

It is perhaps unsurprising that Salvador Dal has proven to be one of the most popular artists of the 20 th century, for his finest works explore universal and timeless states of mind, and most of his pictures were painted with a mastery of traditional representation that has proven rare in our time. For many people, that acute realism alone would have sufficed to attract them to Dals work, and it has certainly served to mask any gradual lessening of quality in his art. Moreover, Dal was also probably the greatest artistic self-publicist in a century in which (as Igor Stravinsky commented in 1970) publicity gradually became about all that is left of the arts. In this respect he was in a class of his own for much of his lifetime, as was his brilliant wife and co-publicist, Gala.

Yet Dals immense popularity is also rather ironic, for his work in its finest phase, at least constitutes an attack on the social, sexual, and cultural mores of the very society that feted him. The notion that an artist should be culturally subversive has proven central to modernist art practice, and it was certainly essential to Surrealism, which aimed to subvert the supposedly rational basis of society itself. In time, Dals subversiveness softened, and by the mid-1940s Andr Breton, the leading spokesman for Surrealism, was perhaps justifiably dismissing the painter as a mere showman and betrayer of Surrealist intentions. But although there was a sea change in Dals art after about 1940, his earlier work certainly retains its ability to bewilder, shock, and intrigue, whilst also dealing inventively with the nature of reality and appearances. Similarly, Dals behaviour as an artist after about 1940 throws light on the basically superficial culture that sustained him, and this too seems worth touching upon, if only for that which it can tell us about the man behind the myths that Salvador Dal projected about himself.

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dal i Domnech was born on 11 May 1904 in Figueres, a small town in the Catalan province of Gerona in northern Spain, the son of Salvador Dal i Cusi and Felipa Domnech. Dal senior was the public notary of Figueres and, as such, an important and widely respected local official. He was a very forceful man, and it was rumoured that he had been responsible for the death of Dals elder brother, also named Salvador, who had been born in 1901 and who died in 1903; officially the death was caused by catarrh and gastroenteritis but according to Dal, his older brother died of meningitis that had possibly been brought on by a blow to the head. Certainly that death left Dals parents with an inescapable sense of anguish, and the young Dal was always aware of the demise because both parents constantly projected his lost brother onto him, every day making comparisons between the two boys, dressing the younger Salvador in his deceased brothers clothes, giving him the same toys to play with, and generally treating him as the reincarnation of his departed brother, rather than as a person in his own right.

Faced with such a denial of self, Dal understandably mutinied in an assertion of his own identity, whilst equally rebelling against the perfected image of the dead brother which his parents attempted to impose upon him. Thus the painter later recounted that, Each day I looked for a new way of bringing my father to a paroxysm of rage or fear or humiliation and forcing him to consider me, his son, me Salvador, as an object of dislike and shame. I threw him off, I amazed him, I provoked him, defied him more and more. If Dals later claims are to be taken seriously, among other things his rebelliousness involved him in deliberate bed-wetting, simulated convulsions, prolonged screaming, feigned muteness, jumping from heights, and acts of random aggressiveness such as flinging another little boy off a suspension bridge or kicking his younger sister in the head for no apparent reason. Supposedly Dal also frequently overcompensated for the suppression of his identity by indulging in exhibitionist behaviour, as when he placed a dying, ant-covered bat in his mouth and bit it almost in half. There is probably only a very limited amount of truth in these assertions, but eventually both Dals innate rebelliousness and his exhibitionism would serve him in good stead artistically.

Jean-Franois Millet (1814-1875),

The Angelus, 1857-1859.

o il on canvas, 55.5 x cm .

Muse d Orsay, Paris.

Dal received his primary and secondary education in Figueres, first at a state school where he learned nothing, and then at a private school run by French Marist friars, where he gained a good working knowledge of spoken French and some helpful instruction in taking great artistic pains. The cypress trees visible from his classroom remained in his mind and later reappeared in many of his pictures, while Jean-Franois Millets painting The Angelus, which he saw in reproduction in the school, also came back to haunt him in a very fruitful way. But the main educational input of these years clearly derived from Dals home life, for his father was a relatively cultured man, with an interest in literature and music, a well-stocked library that Dal worked through even before he was ten years old, and with decidedly liberal opinions, being both an atheist and a Republican. This political non-conformism initially rubbed off on Dal, who as a young man regarded himself as an Anarchist and who professed a lifelong contempt for bourgeois values.

More importantly, the young Dal also received artistic stimulation from his father, who bought the boy several of the volumes in a popular series of artistic monographs. Dal pored over the reproductions they contained, and those images helped form his long term attraction to 19 th -century academic art, with its pronounced realism; among the painters who particularly impressed him were Manuel Benedito y Vives, Eugne Carrire, Modesto Urgell and Mariano Fortuny, one of whose works,